The Creative Craftsman: Adorning The Torah, One Crown At A Time

By Olivia Friedman

Olivia Friedman received her M.A. in Bible from the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies. Based in Chicago, she is a Judaic Studies teacher, tutor, writer, and lecturer and can be reached at oliviafried-at-gmail-dot-com.

It’s not surprising that there are many overlooked biblical commentators. However, R’ Zalman Sorotzkin's is one who ought to be rescued from relative obscurity. Sorotzkin’s biography and tumultuous history helped shape his unique outlook upon Tanakh. His vision and appreciation for cultural context allows readers access to the text via the road of personal relevance. His biblical commentary’s contemporary resonance will recommend him to modern day Jews in particular.

Biography

Born in 1881 in Zachrina, Lithuania (Sofer), he was influenced by his father, R’ Benzion, a man who spent much of his time learning Torah and bringing others closer to God (Anonymous 4). A brilliant orator, R’ Benzion had the ability to move people to tears. This last extended even to his son, whom he always cautioned, warning him that if he did not shed tears when he prayed the words ‘And light up our eyes with Your Torah’ he would not be successful in his studies that day (Anonymous 4). R’ Benzion’s wife, Chienah, was the daughter of the sage and kabbalist R’ Chaim who wrote the work Divrei Chaim on the Torah (Anonymous 4). Born to two such illustrious people, it was hardly surprising that Zalman, a young prodigy, applied himself to his studies. He learned in his father’s house and then in the famous Slobodka yeshiva alongside the esteemed R’ Moshe Danishevsky, choosing later to study in Volozhin under R’ Raphael Shapiro (Anonymous 4).

Zalman created a name for himself due to his diligence and success in his studies; his reputation spread throughout the land and even reached Telz. Rabbi Eliezer Gordon, Dean of Telz, gave R’ Zalman Sorotzkin his daughter’s hand in marriage. Her name was Sarah Miriam. Once married, Sorotzkin chose to learn in seclusion for many years in Volozhin, after which he returned to Telz because the yeshiva had burned down. He accepted the position of principal in order to rebuild the yeshiva, a mission he successfully completed (Anonymous 5). Upon the death of his father-in-law, he was invited to Voronova, which is situated between Lidda and Vilna, to be the spiritual leader and Rav. R’ Zalman accepted the offer and immediately set his sights upon recreating the city. At this time he also became good friends with R’ Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, who lived nearby in Vilna (Sofer). As soon as R’ Zalman came to Voronova, he made a yeshiva for young students and did his utmost to forge strong relationships with the community members, who saw him as a mentor, teacher and spiritual guide (Anonymous 5).

When he had completed his task in Voronova, R’ Zalman determined to move to Zhetel, where he focused on important work such as constructing its Talmud Torah (Sofer) and offering support in the areas of financial upkeep of the home. Sorotzkin was never divorced from the reality of everyday living or hardships within the Jewish communities. Indeed, such hardship and misfortune struck him as well. Upon the arrival of World War I, he and his family were forced to flee and escape to Minsk (Sofer).His name having preceded him, upon his arrival he immediately utilized his time and energy in serving the people of the community, specifically working to ensure that as many rabbis and Torah students as possible could be spared from conscription to the Russian army (Anonymous 5).Sorotzkin traveled to St. Petersburg and due to his connections with General Stasowitz, “managed to procure ‘temporary deferments’ for hundreds of rabbis who were not recognized by the Polish government” (Sofer). Due to a mistake on General Stasowitz’s part, these deferments remained in effect throughout the entire period of the war. R’ Sorotzkin also spoke and offered words of encouragement and praise to the Jews of the community; he was known to possess a golden tongue (Anonymous 5).

After the war was over, Sorotzkin returned to Zhetel briefly. Due to his fame and abilities, he was courted as potential Rav by many different communities; in 1930, he finally determined to head the community of Lutsk. He transformed the community, working to ensure that the schools and yeshivot were of top quality (Sofer) while also focusing on national matters. He was appointed by R’ Chaim Ozer Grodzinski to head the Committee for the Defense of Ritual Slaughter, as Poland had determined that halakhic ritual slaughter was cruel. When the law against ritual slaughter was passed, R’ Sorotzkin countered by “placing a ban on meat consumption” (Sofer). Three million Polish Jews no longer purchasing meat was enough to cause cattle-owners to place pressure upon the government, who then cancelled the decree. When the Polish government decided to establish an elite rabbinate, one of those chosen was R’ Zalman Sorotzkin (Anonymous 6).

Upon the outbreak of World War II, the Soviet authorities planned to arrest R’ Zalman Sorotzkin (Anonymous 6). Thus, he and his family were forced to flee to Vilna, where R’ Chaim Ozer Grodzinski “instructed him to immediately attend to the needs of the yeshivas” (Sofer). It was only once Vilna was taken over by the Bolsheviks that Sorotzkin and other escapees began a long, arduous journey to Israel (Anonymous 6). They were helped by the sages and rabbis in America.

Despite the many tragedies that had occurred in his family (the loss of his only daughter, his son, his father-in-law and grandchildren during World War II), R’ Zalman Sorotzkin remained undeterred and threw himself into communal obligations once more. He created a Vaad HaYeshivos in Israel similar to the one that had existed in Vilna. Its first task was to “provide a financial base for the yeshivas” (Sofer). When Agudas Israel was organized in Israel and the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah [Council of Torah Sages] was formed, the Gaon R’ Isser Zalman Meltzer was appointed and R’ Sorotzkin was chosen to assist him. After R’ Isser Zalman Meltzer passed away, R’ Sorotzkin took over the position as head of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah himself (Anonymous 7).

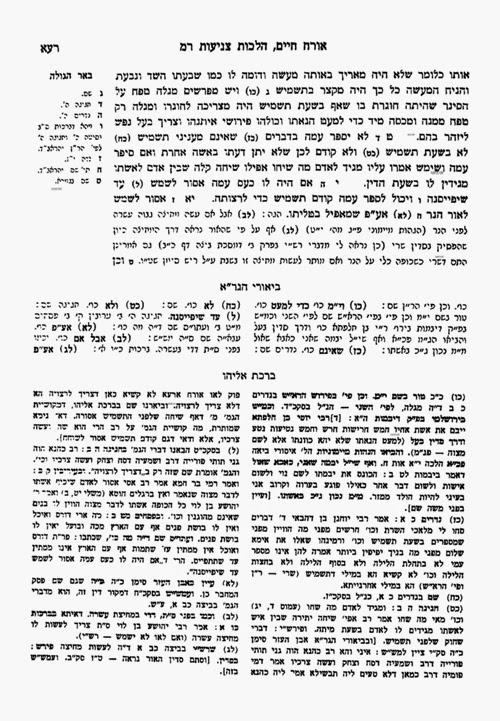

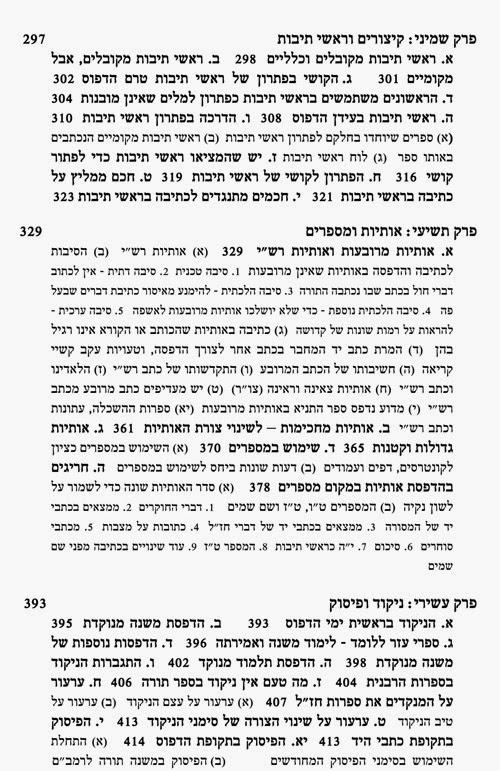

When the Israeli government decided to start government-structured education and do away with certain aspects of Judaic education that had existed until then, the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah banded together in order to create a chain of schools that would accord with their views on education (Anonymous 7). The plan by the Israeli government was to create three different streams of education- “one for general Zionism, one for Labor-oriented Zionism, and one for the Mizrachi” (Sofer). Later, the government wished to reduce these streams to two- “a secular state system and a religious state system” (Sofer). This was not something the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah could support; they had very particular views regarding Jewish education and having their curriculum approved or managed by the government was unacceptable. They therefore created the Chinuch Atzmai initiative. R’ Zalman Sorotzkin took over leadership for this project and put much effort into it. He started many schools while simultaneously recording his novel insights into Torah, publishing several works, including Aznayim L’Torah, his commentary on the Torah, Moznayim L’Torah, his commentary on the festivals, and HaDeiah v’HaDibur, which focuses both on Torah and the festivals. Having dedicated his life to the betterment of circumstances for the Jewish people, he passed away on the 9th of Tamuz 5726 (1966).

Masterwork

One of R’ Zalman Sorotzkin’s seminal works – perhaps the seminal work - was his Aznayim L’Torah [Ears for the Torah]. His introduction to the work, printed in front of his commentary to Genesis, contains his personal outlook on life and an explanation of what inspired him to write this commentary. He begins by noting the distinction between simple praise and the higher level of praise and thanks. Praise is offered when someone does a positive action in a normal or traditional manner. But the higher level of praise and thanks occurs when someone does something in an unusual way, where they are coming from a place of love and compassion. Sorotzkin argues that all of the Jews who were blessed and gifted with survival after the horrors of World War II need to thank God for their salvation. All the more so does this apply to those who were lucky enough, like himself, to make their way to the land of Israel.

Sorotzkin’s humility is demonstrated by his passionate belief that he, his wife and his family are so insignificant in relation to the many other people who perished in the Holocaust. “Who am I and who is my household that You saved us?” he questions God. He explains that he feels truly blessed that he was able to see his books in print and come to Israel where he could serve God. Then, shockingly, he also blesses and praises God with regard to all the horrors that had been visited upon him. Despite the fact that many of his family members perished in the Holocaust, he chooses to see this as the will of God and thinks that he too has a portion in their blood of atonement. He wholeheartedly believes that God will be good and avenge their blood and that because of this physical death they have all earned eternal life.

At this point in the introduction, R’ Sorotzkin begins to delineate the sources and motivations for his commentary. There are four of them. First, he credits his rebbe, who taught him Chumash [Bible] and accustomed him to review it diligently. There were times that R’ Sorotzkin reviewed an entire book of the Five Books in a day, and completed all five within the week. Due to this wide exposure to Tanakh, R’ Sorotzkin was given a wonderful background off of which to compose speeches and to find answers to the problems of life within the Torah.

Second, he credits his son. He desired to fulfill the commandment of V’shinantam l’vanecha [and you shall teach/ make it sharp for your son] for at least one day a week without making use of a shliach [agent]. Thus, he accustomed himself to learn the portion of the week on the Sabbath with his son, doing his utmost to plant the seeds for love of Torah and fear of God. His son had many excellent questions and R’ Sorotzkin explains that he learned a lotfrom his son, who would offer lots of novel insights to him.

Third, R’ Sorotzkin was not limited to learning with his son but also learned with many other people. He explains that throughout his career in Lutsk, Zhetel and Voronova and continuing to Jerusalem, he would give over short speeches and lectures themed as pertaining to Torah. In this way he created flowers and adornments for the section of the week, beautifying it and making it holy. He tried to find connections between the Written Law and the Oral Law in order to truly connect with and reach other people.

Fourth, R’ Sorotzkin was bothered by all the troubles that beset the Jews- decrees, wars, a time of destruction, leaving religion, breaking educational boundaries and exile. He therefore decided to write a commentary that would speak to the times and address the issues of the generation, trying to show his beleaguered people that the light of God that comes from understanding the Bible and Prophets may illuminate their lives as well.

R’ Sorotzkin writes that he looked over his lifework a number of times before publishing it, adding sections and subtracting others until he felt that he had truly created his masterwork. He specifically chose the name Aznayim L’Torah because it reflected the essence of the work- this demonstrates his own experience in listening to the messages the Torah conveys as well as the way in which the book was formed, through listening to the ideas and insights of others (such as his students). Perhaps the most important aspect of Sorotzkin’s work was his clear desire to enable it to be accessible to all. He offers a guide as to what many different members of society will be able to discover within its covers. Rabbis and scholars will appreciate finding the words of our sages and other interwoven concepts in clear and concise language. Teachers will find explanations and clarifications in accordance with the simple understanding of the text and ideas that will enter into the minds of their students. Learned people will find new insights and explanations, specifically words that are accepted into the heart. In this way, his commentary aims to be useful to and appreciated by all.

Sorotzkin explains a stylistic choice he made regarding his utilization of the words ‘Maybe’ or ‘Perhaps’ throughout his commentary. He explains that he wrote his commentary keeping the adage of the Tosfos Yom Tov in mind (Brachot 85: 44) that it is permissible to offer explanation and commentary on the Torah only via the method of explicating the simple understanding or a more complicated understanding so long as one does not claim this is the final and inarguable mode of comprehending the text. Sorotzkin explains that his commentary reflects his thoughts and the reader is welcome to take them or leave them; he understands that there are seventy facets to the Torah and the reader should feel free to choose whichever snippets of his commentary speak most to him.

Sorotzkin concludes by dedicating his work to the memory of his father and mother, whom he praises and admires, and thus begins the reader’s journey into the mind and methods of a nobly intentioned man.

Examples of Sorotzkin’s Unique Approach Via Deuteronomy

What Sets Deuteronomy Apart

Sorotzkin begins his commentary to the Book of Deuteronomy by noting the distinct differences between this book and the other four books of the Torah. The other four books are linked to Genesis and appear to be one Torah, but this work begins with the words ‘These are the words’, making it stand alone. It even has its own title, he explains- that of Mishnah Torah. The second distinction appears in the way the narrative is told over. Throughout the rest of the Torah, lashon nistar – secretive or hidden language- is utilized. Events are told over in the third person: ‘And God spoke to Moses.’ In contrast, here much of the book is recorded in the first person. Third, the content of Deuteronomy is quite different: it seems to be review of precepts formerly discussed in the other works alongside rebuke and chastisement. Fourth, aside from the title Mishnah Torah, the work has another name, Sefer HaYashar [The Book of the Righteous] which also requires explanation.

Sorotzkin argues that the entire Torah is from God and anyone who suggests that even one verse was written by Moses of his own initiative is incorrect. If so, however, why are there all the aforementioned distinctions between this work and other works? R’ Zalman explains that it would have been difficult for a generation steeped in idolatry to serve God appropriately, which was part of the reason that God decreed that the generation had to stay in the desert for forty years, during which time its children could grow up knowing only God and unfamiliar with idols and other forms of impurity. Moses wished to ensure that this second generation would not sin and thus wanted to paint a vivid picture of all that had transpired in order to warn and guide them so that when they crossed the Jordan they would not be lost. Sorotzkin cites the Abarbanel who explains that first Moses spoke these words and afterwards God gave him leave to include them within the Torah. Thus, the fact that they were written within the authoritative text was not of his own initiative. Due to this work’s emphasis on reviewing the commandments and offering rebuke, it was entitled Mishnah Torah.

Yet why was it entitled Sefer HaYashar? This is due to the verse in Deuteronomy 6: 18, ‘And thou shalt do that which is right and good in the sight of the Lord that it may be well with thee.’ Yet doesn’t it also mention the word ‘yashar’ in Exodus? Yes, explains R’ Sorotzkin, but the word is mentioned far more frequently in Deuteronomy than Exodus and the title of a book follows the frequency of the topic/ theme mentioned therein. He cites the Maharsha, who explains the verse in 6:18 as referring to the need to operate lifnei m’shuras ha’din [above and beyond the letter of the law]. Moses is thus instructing the Jews to follow God’s law but not just the letter of the law; rather, the spirit of the law as well.

R’ Sorotzkin then offers a beautiful understanding of the Midrash Rabbah which suggests that this particular work was found in Joshua’s hands and that it is thus understood that the King of the Jews must carry it with him at all times. Since all of the Torah is meant for all Jews, why is Deuteronomy specifically offered to/ meant to be found upon the person of a king? R’ Sorotzkin explains that it is because the king has special powers to put people to death simply due to his law (outside of the typical workings of a Jewish court). Thus, the king might be tempted or fall prey to acting in a cruel manner. It is specifically this book which focuses upon the need to operate in a way which is above and beyond the letter of the law that will remind him that he is accountable for his actions and it is better to be merciful and charitable, as King David was, than to be too quick to punish. This is the reason that throughout Tanakh the words yashar [righteous] and tov [good] are associated with David and those who follow in his footsteps. This explains the reason that this work specifically should not be forgotten and should not ever be absent from a leader’s lips; he must know and understand and remember the need to act in a just and righteous manner so as not to betray God and the mission God offered him.

Various Orientations to Text- Literary, Realistic, Personal, Psychological

R’ Zalman Sorotzkin’s commentary is both beautiful and peculiar in that it does not seem to follow simply one methodological method or attempt to reach one goal. Since the main themes that motivated him in the writing of it were accessibility to the populace and speaking to the times, it is perhaps not surprising that his analysis, ideas and thoughts are so varied. He particularly focuses upon literary and psychological problems within the text, but also appeals to modern readings of the verses in addition to consistently comparing verses that appear within one text to those found in a different place. By dint of these comparisons he desires to draw out a point, sometimes an important and overarching message that helps demonstrate the particular significance of the passage he is currently explicating. The varied and sporadic nature of his commentary typifies its genius. There is something here for everyone, from the child to the scholar. It is almost like attending a banquet where many sumptuous foods and delicacies are served. One person may prefer the chocolate mousse while another may enjoy tenderloin steak, and both are lovingly presented upon the table.

Sorotzkin’s careful reading of verses translates to a fascinating analysis ranging from the more obvious understanding that Deuteronomy begins without use of the conjunctive vav to his more subtle reading of Deuteronomy 1:5. There, R’ Sorotzkin questions how it would help to ‘explain’ the Torah in foreign languages seeing as the Jews would not have understood these languages. He then offers a reading where the Hebrew word lashon means ‘idiom’ and thus Rashi is referring to the fact that Moses in fact explained the seventy facets of the Torah as opposed to writing them down in different tongues. Sorotzkin is concerned with reality and with events making sense on a logical plane; thus his worry over an ‘explanation’ that wouldn’t actually help explain anything!

Similarly, in keeping with his desire to link the Written Torah and Oral Torah, Sorotzkin’s careful literary analysis allows him to demonstrate that there are places where this must be so. In Deuteronomy 1:11, he comments on the words ‘May God add to you…a thousand times yourselves.’ In keeping with Maimonides’ understanding regarding cities of refuge, where an additional three cities were not yet added and thus it means that they will be added in the time of Messiah, Sorotzkin notes that there has not yet been a time in history where there have been six hundred million Jews. Since the Torah does not offer false promises, he argues, this blessing too must refer to a future time (that of the Messiah).

Yet his literary awareness also leads him to shed light upon deceptively simple texts. For instance, in Deuteronomy 2:6, he comments to the verse ‘You shall purchase food...so that you may eat, also water…so that you may drink.’ After citing other commentaries’ explanations of this verse, the question being why it was necessary to explain that the people would eat or drink the food (isn’t that evident?) he offers his own, elegantly linking it back to the complaints registered against the manna in Numbers 21:5. There, the Hebrews had declared that they were ‘disgusted with the insubstantial food.’ There were also those who found fault with the water from the miraculous well, as stated by the Netziv. Here, notes R’ Sorotzkin, the people will have a chance to purchase food and water as opposed to the manna and miraculous well upon which they had previously been subsisting. God knew, however, that as soon as they did so they would realize that they had in fact lacked nothing for the forty years in which they had traipsed through the desert, and that God’s food was superior to anything they could purchase. Thus, the simple explanation of the verse is that the Hebrews purchased food as opposed to eating their own because they longed for something to eat which was not miraculous in origin.

R’ Sorotzkin’s appreciation for stylistic literary choices is further demonstrated in his understanding of Deuteronomy 1:44. He elaborates upon the verse ‘As the bees would do,’ creating an extended metaphor that explains how precisely the actions of these men who desired to possess the land of Israel were akin to those of bees. He explains that “[b]ees make honey, but also sting” (Lavon 24) which is why, when a beekeeper desires to harvest his honey, he must first light a fire with green wood, which will send up lots of billowing smoke. The bees “run inside the hive and cower” (Lavon 25) upon smelling the smoke, at which time the beekeeper is able to harvest the honey. In contrast, someone who desires to steal the honey will not be able to announce his presence by kindling a fire. Thus, he must approach unshielded and the bees will sting him to death. In the end, he must flee in order to preserve his life (Lavon 25).

Similarly, explains R’ Sorotzkin, the men who wished to possess the land of Israel did so unlawfully and therefore the pillar of cloud which accompanied them in the desert did not protect them. Indeed, if they had received God’s explicit command and blessing, that cloud would have annihilated their enemies and caused them to fall dead in their path. The Jews would then be able to possess the land which was flowing with milk and honey, the Amorites having left them untouched. However, “when these willful people barged in unlawfully, they were like thieves seeking to take honey from the hive without a smokescreen” (Lavon 25). For this reason, the Amorites were able to fall upon them “like bees” (Lavon 25) and far from conquering the land flowing with milk and honey, these Hebrews lost their lives in the attempt. Sorotzkin’s reading is imaginative, creative and extremely vivid; he takes one sentence within the verse and conjures up an entire scenario which adds flavor and meaning to the text.

Sorotzkin’s playful personality arguably appears in his analysis of Deuteronomy 3:26. There, God has informed Moses that rav lach [it is too much for you]. Sorotzkin interprets this as a literary play on words. Rav lach could also mean ‘a Rabbi for you.’ Moses had suggested that even if he was not permitted to lead the Israelites into the Promised Land, perhaps he could act as an ordinary citizen and follow Joshua’s command. God’s answer to this was rav lach- ‘acting as a Rav is the task for you’ and that he would be unable to be a mere student. Sorotzkin notes that this fits perfectly with the Midrash Tanhuma’s understanding that after Moses learned Torah from Joshua he said, “Until now I requested my life, but now, my soul is Yours for the taking.”

Aside from puns and creative interpretation, Sorotzkin’s commentary is also sprinkled with comments that show his humility. In his commentary to Deuteronomy 1:15, he gives credit to his nephew for the explanation he offers. In Deuteronomy 1:15, he frankly admits that he did not fully understand the Vilna Gaon’s holy words. He is not shy of admitting his lack of understanding. Similarly, in Deuteronomy 1:46, he seems puzzled, explaining that he cannot understand why Rashi offered an interpretation that is contrary to the one found in Seder Olam. This is aside from the fact that his commentary as a whole is peppered with sources outside of himself, whether they are traditional greats like Rashi, Maimonides and the like or the Vilna Gaon, Melo HaOmer or Ka’aras Kesef. Sorotzkin clearly valued the contributions of those other than himself and uses them as springboards off of which to base his own ideas.

Perhaps Sorotzkin’s most compelling renderings of Tanakh appear in his psychological readings of various verses. Indeed, he often links the literary to the psychological, noticing particular wording in a verse or the placement or juxtaposition of several verses, and then coming to conclusions about the significance of this order. In his commentary to Deuteronomy 1:1, ‘The words that Moses spoke,’ Sorotzkin explains that people will listen to a speaker for one of two reasons. One: The speaker may be a gifted orator who knows how to latch onto and grab hold of the hearts of men. Two: He is speaking on behalf of a famous and important person, and thus even if his tongue is made of stone, he will still command attention. For this reason, when Moses speaks with God by the burning bush, the objections he has reflect his psychological state. Moses realizes that he will not be able to command the attention of the Hebrews because they do not know who God is and thus will not attend since reason two will not apply in their case. Due to this, he concludes his conversation with God by explaining that he is not a man of words as opposed to opening with that objection.

Similarly, in his commentary to Deuteronomy 1:17, Sorotzkin is surprised by Moses’ language. The verse seems to suggest that Moses sees himself as capable of solving any problem; indeed, he declares that “any matter which is too difficult for you, you shall bring to me and I shall hear it” (Deut 1:17)! How can it be that the humblest man on earth, deemed so by God Himself, can be so arrogant as to suggest that he will be able to solve any problem, no matter how thorny? R’ Sorotzkin delves into the psychological underpinnings of Moses’ statement and determines that in fact there is no contradiction at all. What Moses is really stating is that perhaps the judges will come upon a difficult litigant who will not allow them to proceed in their task. Under such circumstances, since Moses has already warned the judges not to ‘tremble before any man,’ he now cautions them that if a litigant comes before them who is too difficult for them, “’bring [this case] to me and I shall hear it,’ for I am willing to suffer the slings and arrows of this difficult man” (Lavon 15). Far from declaring his superiority and claiming that he has the ability and insight to rule in every single case, Moses is acting humbly, explaining that he is not too proud to bear the contempt of a dissatisfied plaintiff.

But it does not end there. Sorotzkin’s entire interpretation of the phrase ‘As the Lord, your God, commanded you’ (Deuteronomy 5:16) as it refers to the commandment of honoring one’s father and mother reflects his sensitivity to the psychological conditions under which that generation had been raised. He explains:

Normally, children’s love and respect for the parents who brought them into the (present) world grows steadily through the years. The more the child enjoys his life, the more happiness he discovers, then the greater will be his love for the parents who gave him this happy life.

In the plains of Moab, Moses was confronted with children who had suffered greatly from wandering in the desert, all because of their parents’ misdeeds. It was their parents who had brought down upon them the decree that “Your children will roam in the Wilderness for forty years and bear [the guilt of] your guilt” (Numbers 14:33). Therefore Moses stressed what God had told him on Mt. Sinai: that this commandment must be done “as the Lord, your God, commanded you”: to honor your parents during their life and afterwards, regardless of how well or ill satisfied you are with your life. (Lavon 79)

Once again, Sorotzkin succeeds in making the Torah a contemporary and caring book, demonstrating that Moses understood and spoke to the nation’s psychological state.

Sorotzkin’s practical advice and use of anecdotes and stories to flavor his point helps him to fulfill his goal of making his commentary easy and accessible. In his commentary to Deuteronomy 1:1 on ‘These are the words that Moses spoke’ he explains that Moses only engaged in words of Torah, a small matter in those times. Relating the point to his own generation, however, he mentioned that:

For Moses, a man of God, this was merely a minor accomplishment. Yet in our own times we merited the example of the Chafetz Chaim, zt”l, who used his tendency to be talkative as a tool to keep away from sin. In order to avoid speaking or hearing idle words, he would talk endlessly to both students and visitors about Torah subjects and Jewish ethics. The great tzaddik R’ Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, zt”l, bore witness that the author of the Shemiras HaLashon guarded his own tongue in a most original way: not by keeping silent, but by always fulfilling v’dibarta bam so that there was never a moment for idle talk. (Lavon 3)

Similarly, in his commentary to Deuteronomy 1:1 on the words ‘To all Israel,’ he offers an example from his time, stating:

A story is told about a gaon who was famous for his moving discourses. Everyone would run to hear him speak and listen to his words of rebuke. After his death, his discourses were collected and published, but for some reason they did not have a profound effect on their readers. People commented that although these were the very same speeches they remembered hearing from the great man himself, something was missing—the sigh that would escape his lips when he paused. That sigh, which rose from the depths of his heart, broke their hearts when they heard it. For only words that come from the heart can enter the heart. (Lavon 4)

Through interweaving these stories and anecdotes, Sorotzkin manages to capture the attention of an element who might not feel connected to the text otherwise.

His penetrating psychological insights and evaluations of characters within the text also help to add a dimension of reality to an otherwise distant story. For example, Sorotzkin notices that Moses states “I cannot carry you alone” in Deuteronomy 1:9 only to later state “How can I alone carry your contentiousness?” in verse 12. Why the need for repetition? Answers R’ Sorotzkin:

The fact is that being a ruler of Israel is similar to being a slave. Even after Moses, the acknowledged ruler of his people, decided that he was unable to bear all their problems and judge all their cases himself, as he declares in this verse, he asks himself what the people will say. Perhaps his ‘masters’ would think he was shirking his duty towards them, and that he was really capable of bearing the burden by himself. Therefore, he asked them if they agreed with him (v. 12). Let them tell him, if they can, how he can bear it all by himself! Only after they answered him, “The thing that you have proposed to do is good” (v. 14) was his mind at ease. (Lavon 10)

Through careful reading of the verses and appreciating the literary significance of the seeming repetition, R’ Sorotzkin seeks to unveil the thoughts that were pressing upon Moses’ mind. Similarly, in Deuteronomy 2:6 in his commentary to the verse ‘Also water shall you buy from them for money’ R’ Sorotzkin deducts the Israelites’ state of mind from the unusual Hebrew word used to mean ‘buy.’ The word is tikhru. R’ Sorotzkin explains that Scripture uses this rare word due to the fact that “the Jewish people may have considered digging a cistern on Edomite land without permission” (Lavon 30). The word tikhru means both ‘buy’ and ‘dig.’ Thus, the hint being given is that if the Israelites wish to “dig for water, they must buy the water!” (Lavon 30)

R’ Sorotzkin often identifies echo narratives or notes places where he feels light can be shed by making a comparison (of characters, texts or storylines). In Deuteronomy 1:3, when commenting on ‘In the eleventh month, on the first of the month’ Sorotzkin compares Moses to R’ Hanina bar Papa. He notes that Moses reviewed the Torah with the Jews for a total of thirty-six days, since he began on the first day of the eleventh month and concluded on the seventh of Adar. In contrast, R’ Hanina reviewed Torah for a mere thirty days. Why did it take the latter sage less time? The difference, argues R’ Sorotzkin, is contained in the mode of study and delivery. Moses was speaking to the entire people and needed to elucidate the commandments before all of them whereas R’ Hanina was only learning for and by himself. Thus, the seeming discrepancy is explained.

While in that case Sorotzkin drew a comparison between a character in Tanakh as opposed to a different one who appears in the Talmud, he also uses his comparison technique and notices differences and similarities between various characters when solely in their Tanakh context. In his commentary to Deuteronomy 3:27 on ‘For you shall not cross the Jordan’ he explains:

Joseph spoke with pride about his native land, saying, “For indeed I was kidnapped from the land of the Hebrews” (Genesis 40:15). He was therefore rewarded with burial in his own land. Moses did not admit to his native land. When Jethro’s daughters said of him, “An Egyptian man saved us” (Exodus 2:19), he heard and was silent. Therefore, he did not merit burial in his land (Deuteronomy 2:8).

People commonly point out that Moses not only refused to admit his native land, but he also denied his people. For Jethro’s daughters called him ‘an Egyptian man’ and that is not only a land but a people. Why was he not punished for this denial as well?

Perhaps we can explain this in accordance to the Midrash. When Potiphar saw the Ishmaelites offering Joseph for sale, he said to them, “In all the world the white people sell black people and here are black people selling a white man! This is no slave” (Genesis Rabbah 86). Since the Egyptians were even darker-skinned than the Ishmaelites, everyone must have known that the Jethro’s daughters weren’t referring to Moses as an ethnic Egyptian when they said that “an Egyptian man” had saved them. Clearly he was of the lighter-skinned Hebrews living in Egypt at the time- a resident of the country, but not one of its natives. At this point, Moses should have corrected them and told them that he was not an Egyptian at all, but “from the land of the Hebrews.” (Lavon 51)

Sorotzkin not only delineates the differences between the two characters but also uses an appeal to common sense as understood by the Midrash. The Midrash offers its commentary based on (in its view) the realistic approach that Joseph was white and that slaves who were commonly sold were black. This is enough of a proof to demonstrate that Moses could not possibly have been seen as a true Egyptian. Sorotzkin’s appeal to the cultural standard, milieu or conditions of the time is not only expressed here, but often occurs within his commentary. He deliberately chose to read the Bible with modern eyes. In his commentary to the verse ‘Then you spoke up and said to me, ‘We have sinned to God!’(Deuteronomy 4:1), he explains that “[p]erhaps by behaving this way they were straying into the ways of idolaters, who customarily confess sins before their priests” (Lavon 24) which is “not the way of Israel, who confess their sins directly before God- after asking forgiveness from the person they have wronged, if it is a sin between man and his neighbor” (Lavon 24). Sorotzkin’s reference to the practice of confession echoes Catholic practice and creates a situation where the general populace can understand why it was improper for the Hebrews to come weeping to Moses as opposed to simply turning to God.

Another example of R’ Sorotzkin’s awareness of the times appears in his commentary to Deuteronomy 12:8 on the verse ‘Every man what is proper in his eyes.’ He sadly notes:

Look at the difference between recent generations and the generation of Moses.

In more recent times when we talk about, ‘You shall not do…every man what is proper in his eyes,’ we mean things like theft, robbery, adultery, murder or even idolatry, whereas in the generation of Moses, it meant that one must not bring a sacrifice to God on a bamah, a private family altar. Private altars were permissible at that time, of course, but here the Torah is referring to someone who brings to a private altar one of those sacrifices which should be offered only at the national atar at Shiloh.

Times change, and we change with them. (Lavon 154)

Similarly, Sorotzkin understands the verse in Deuteronomy 12: 23, ‘Only be strong not to eat the blood’ as referencing blood libels in addition to the typical explanation of the verse, which refers to simply not partaking of the lifeblood of an animal. As part of his commentary, he writes:

A Jew has a “face-to-face” battle with blood, to the point where, if he finds a speck of blood in the egg, he throws away the entire egg.

Yet, even though the gentiles see how Jews are repelled by any sort of blood, they do not hesitate, nor do they feel the slightest shame, to bring “blood accusations” against us. This battle, too (an attack from behind) must be fought by us, by convincing just-minded people among the nations that such accusations are groundless.

It could be that this kind of ‘blood,’ too, is included in the Torah’s dictum: “Only be strong not to eat the blood,” and that the Torah is encouraging us to remember that with the merit of this mitzvah “it will be well with you and with your children after you” forever, and the gentiles who spilled your blood will perish. (Lavon 161)

Could there be a more apropos understanding of the verse in the light of the recent horror that was the Holocaust? When Sorotzkin looked at this verse, he saw it with eyes that had witnessed the mass spilling of Jewish blood and therefore sought to find places where God promised to avenge this loss.

In Deuteronomy 13:4, R’ Sorotzkin once again makes use of explanations gleaned from the times in which he lived. He elucidates the verse ‘Do not hearken to the words of that prophet or to that dreamer of a dream, for the Lord, your God, is testing you’ in the following light:

This verse was used by the community of converts that flourished in the time of the Czars along the shores of the Caspian Sea, to refute the priests sent by the Russian government to attempt their return to the Christian fold—Their fathers had been Christians for centuries, but suddenly they had seized upon the idea of converting to Judaism, owing to their habit of constantly reading Scripture on the Christian holidays.—The priests began to tell them all of the signs and wonders that the man the Christians worship had done, and asked them, ‘Was this not enough to warrant believing in his prophetic message?” But one of the elders answered that this man’s prophecy was based upon the Torah of Moses, and there is written, “If there should stand up in your midst a prophet or a dreamer of a dream, and he will produce to you a sign or a wonder…Do not hearken to the words of that prophet…for the Lord, your God, is testing you.” In that case, what use are the signs and wonders that this man showed, seeing as God Himself has warned us not to listen to such a prophet no matter what wonders he performs? (I heard this from the elders of a group of converts when I was in Tzeritzin, now called Stalingrad, visiting my brother, the Gaon R’ Yoel zt”l who was the Rav there and afterwards in Stoipce.) (Lavon 167)

Thus, rather than offering an explanation of the plain meaning of the words, R’ Sorotzkin tells an anecdote that his readers will appreciate and which will demonstrate the real-life applicability of these verses. Sorotzkin constantly sprinkles these anecdotes or references to modern times throughout his commentary. In his understanding of Deuteronomy 13: 7 to the words ‘Who is like your own soul’ he explains that the person being referenced here is one’s father. The father was not listed first in the passage since it was not normal in those times for the father to persuade the son to become an idolater. However, laments R’ Zalman Sorotzkin, “In that case, what can we say about some fathers in our times, who hand their sons over to missionaries? This is a disaster that even the Torah chose not to write out explicitly, only indirectly” (Lavon 169).

In his understanding, comparison with and appeal to modernity, Sorotzkin is able to make his commentary that much more meaningful and more pertinent to his audience. For example, when offering his explanation of the verse ‘And you will be completely joyous’ in Deuteronomy 16:15, he notices that the word ach also appears in another place, namely the verse ‘Only [ach] Noah survived’ (Genesis 7:23). In that case, the sages understood this to mean that ‘even he was coughing up blood because of the cold [in the Ark]’ (Lavon 199). Posits R’ Sorotzkin, “The use of the same word indicates a link between the two verses. We can learn here that even in times of trouble, when Israel is ‘coughing up blood,’ we are commanded to rejoice in our festival” (Lavon 199). As someone who knew what trouble meant, having lost the majority of his family to the Holocaust but still determined to serve and appreciate God with a full and joyous heart, Sorotzkin’s words are particularly resonant.

Does Sorotzkin’s commentary aid in understanding the plain sense of the biblical text? This changes verse by verse. Sometimes Sorotzkin is citing Midrash or drawing grand conclusions through comparing various texts. At other times, he focuses on the literal meaning of the text and the reason for this rendering. However, on a whole, his commentary is more story-driven and thus filled with anecdotes, explanations, lessons, derivations and colorful characterization, than a dry analysis of wording and phraseology. If Sorotzkin is interested in the literal meaning of the verse, it is generally due to the lesson he wishes to derive from it.

His Impact

R’ Zalman Sorotzkin’s stated goal in writing his work was to create a commentary that would be accessible to all and penetrate the hearts of many different sorts of people. For this reason, whether he is carefully analyzing a literary tract, making assumptions about the psychological underpinnings of various characters, utilizing comparisons to shed light upon particular differences or similarities between characters or reading the text with fresh, modern eyes, he works these techniques and insights into his commentary. As an exegete, his commentary is refreshing due to its being so varied. Rather than adopting one methodological perspective and consistently following it, Sorotzkin chose to act as a dilettante, dabbling in many different methods of analysis. In this way, he pays homage to the many different rabbis and sages who have lived over the centuries, working their contributions into his own understanding of the text while simultaneously, at times, differing from them due to his appeal to modern context.

When it comes to the question of what kind of impact Sorotzkin has made upon subsequent commentary on Deuteronomy or the Jewish exegetical world at large, it is difficult to answer. On the one hand, there does not seem to be a well-known definitive or authoritative biography of R’ Zalman Sorotzkin, encyclopedia entries or other official recognition of him. He is not cited by other commentators to the text or used as an authoritative arbiter of disputes. On the other hand, he passed away recently, in 1966. A century hasn’t passed since his death. There is still time for his impact upon exegesis to grow and his words to spread. The very fact that his commentary upon the Torah has been translated into English by Artscroll means that this publishing house has made it accessible to many different people and thus he can still affect the understanding that many have of the text. Especially in our modern society, where Torah learning is institutionalized and often occurs in the classroom as opposed to on one’s own,there is hope that slowly but surely, R’ Zalman Sorotzkin’s ideas and creativity will spread. As his commentary is aimed at the general populace in addition to scholars, and since it contains all manner of innovative ideas, one would think its appeal should be more widespread than it currently is. Unfortunately, as of now his work appears relatively undiscovered. Hopefully, as time progresses, this will change and the man who set out to document the novel insights of his son and students, properly use the breadth of knowledge his rebbe had afforded him, and speak to the times will be recognized as the forward-thinking and warm individual that he was.

Works Cited

Anonymous. Rabi Zalman Sorotsḳin : ...[le-yom Ha-zikaron Ha-rishon...]. Yerushalayim : [Merkaz Ha-ḥinukh Ha-ʻatsmaʼi Be-Erets Yiśraʼel], 1967. Print.

Lavon, Yaakov, Trans. Sorotzkin, Zalman. Insights in the Torah: Devarim. Vol. 5. Artscroll Mesorah, 1994. Print.

Sefer Bereishis ... Min Ḥamishah ḥumshe Torah : ʻim Targum Onḳelos U-ferush Rashi, Baʻal Ha-Ṭurim, ʻIḳar śifte ḥakhamim ṿe-Toldot Aharon ; ʻim Perush Oznayim La-Torah / Me-et Zalman B. Ha-g. Ha-ts. Bentsiyon Sorotsḳin. Vol. 1. Jerusalem: Mekhon Ha-deʻah ṿeha-dib, 2005. Print.

Sefer Devarim ... Min Ḥamishah ḥumshe Torah : ʻim Targum Onḳelos U-ferush Rashi, Baʻal Ha-Ṭurim, ʻIḳar śifte ḥakhamim ṿe-Toldot Aharon ; ʻim Perush Oznayim La-Torah / Me-et Zalman B. Ha-g. Ha-ts. Bentsiyon Sorotsḳin. Vol. 5. Jerusalem: Mekhon Ha-deʻah ṿeha-dib, 2005. Print.

Sofer, D. "Rav Zalman Sorotzkin ZT"L: One of Chareidi Jewry's Main Helmsmen." Yated Neeman [Monsey]. Tzemach Dovid. Web. 4 May 2010. .

In The World that Was America 1900-1945 – Transmitting the Torah Legacy to America by Rabbi A. Leib Scheinbaum, the situation is explained as follows:

Hatzalas Nefashos Supersedes Shabbos

The roshei yeshiva who had escaped to Vilna cabled Rabbi Shlomo Heiman. They informed him of the dire need to immediately raise $50,000, to help the rebbeim and talmidim from the various yeshivas escape imminent death at the hands of the Russians, if the visas and the permits for the trans-Siberian trip from Vilna to Vladivostok could not be purchased. Many gedolim, including Rabbi Aharon Kotler, had escaped to the Vilna area. At this time their lives were endangered. Despite months of work on an escape plan, the Vaad was unsuccessful. Now it aappeared that there was a viable solution. All that was necessary was the cash.

The gedolim in America- Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, Rabbi Shlomo Heiman and Rabbi Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz- considered this a matter of pikuach nefesh (a life and death situation), and as such it superseded even Shabbos. Consequently, on a Shabbos in November 1940, Rabbi Sender Linchner, Rabbi Boruch Kaplan and Irving Bunim traveled by taxi throughout the Flatbush section of Brooklyn raising money, because time was of the essence. With the help of the Almighty, they were successful in raising $45,000 and the Joint released the money- adding the $5000 deficit- to Vilna. Miraculously the rebbeim and talmidim were rescued!

Among the rescued gedolim were the Amshenover Rebbe, Rabbi Shimon Sholom Kalish, Rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin, the Lutsker Rav, Rabbi Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, Rosh HaYeshiva of the Mirrer Yeshiva and the son of the famed Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel (the Alter of Slobodka) who went to Palestine; the Modzitzer Rebbe; Rabbi Reuven Grozovsky, the Kaminetzer Rosh Yeshiva; Rabbi Avraham Jofen, the Novardoker Rosh Yeshiva who came to the United States; and Rabbi Yechezkel Levenstein, mashgiach of the Mirrer Yeshiva who went to Shanghai. (82)