A Mild Case of Plagiarism: R. Abraham Kalmankes’ Ma’ayan Ha-Hokhmah

1. The Accusation.

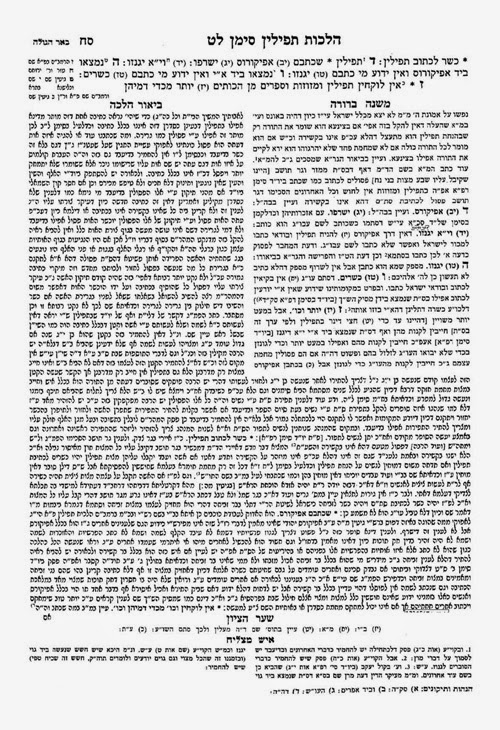

Rabbi Joseph Samuel ben R. Zvi (d. 1703) – more popularly known as ר'שמואל ר'חיים ר'ישעיה'ס – served as a member of the rabbinic court in Cracow for some 26 years, after which he was appointed Chief Rabbi of Frankfurt in 1689.1 An avid collector of books and manuscripts, he made good use of them in listing in the margins of his copy of the Talmud variant readings, emendations, and annotations to the text of, and commentaries on, the Babylonian Talmud. These were published posthumously in the Amsterdam and Frankfurt editions of the Talmud, 1714-21. Today, they are incorporated in every edition of the Vilna Talmud, and every student of the Talmud benefits from the efforts of this great rabbinic scholar.2

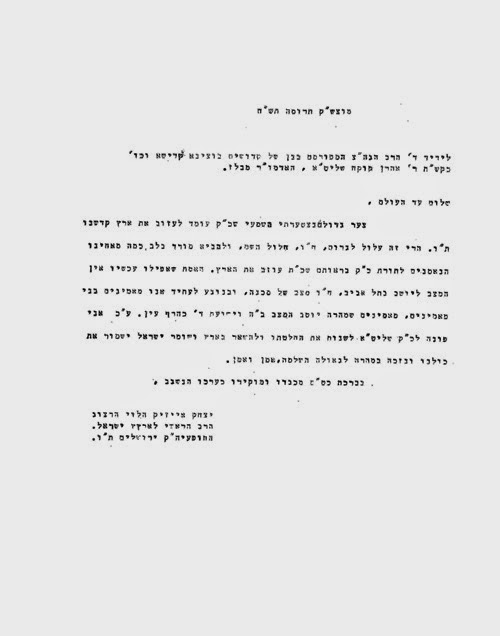

One of the many tasks of the leading rabbis in the 17th and 18th centuries was to write letters of approbation on behalf of mostly young rabbinic scholars seeking to publish their manuscripts. R. Joseph Samuel wrote some 40 such letters of recommendation during his lifetime, not an insignificant number in those days.3 This, despite the fact that he looked askance at the recommendations that many of his colleagues were writing, and was less than impressed by the quantity and quality of books being published. Indeed, at one point he called for – and apparently instituted – a moratorium on the publication of rabbinic works in Germany, claiming that many of them were superfluous and some were even harmful.4

On January 2, 1701, R. Joseph Samuel wrote a letter of approbation for a kabbalistic work by R. Mordechai Ashkenazi, an otherwise unknown author (then) who was a protégé of the distinguished Italian rabbi and kabbalist, R. Abraham Rovigo (d. 1713).5 The book, entitled אשל אברהם, and the letter of approbation, were published later in 1701 in Fürth. After a lengthy critique of the proliferation of works on Kabbalah in the late 17th century, the letter reads, in part:6

They [the new authors of kabbalistic works] are guilty of two evils. First, they neither know nor understand the deeds of God. Second, they cause the common folk to slight the rabbis expert in the exoteric Torah. The common folk assume that rabbis not expert in Kabbalah are not true scholars. So they cast away their expert rabbis, listening instead to the enchanters, whose wisdom is borrowed from others. I can testify that this is true [i.e., that the enchanters’ wisdom is borrowed from others], for I was involved in such a case. I recall vividly how some fifty years ago I owned a copy of a delightful kabbalistic work entitled התחלת חכמה. Some upstart student, a novice with no knowledge based on accumulated learning, printed the book under his own name. He simply plagiarized the entire book.

![]()

![]() 2. The Identity of the Plagiarized Book.

2. The Identity of the Plagiarized Book.

No book entitled התחלת חכמה has ever appeared in print. It therefore could not have been plagiarized by anyone. Moreover, R. Joseph Samuel did not reveal the name of the plagiarist and the title of the book in its plagiarized form. This literary riddle was first raised in print early in 1976 by the noted bibliophile, Abraham Schischa of London.7 The solution was not long in coming. That same year, R. Shmuel Ashkenazi, also a noted bibliophile, solved the riddle.8 He correctly identified התחלת חכמה as the title of a kabbalistic book in manuscript form, still available in a variety of contemporary libraries.9 In book form, it was entitled מעין החכמה and it first appeared in print in Amsterdam in 1652.10 The plagiarist who published מעין החכמה under his own name was R. Abraham Kalmankes of Lublin. Ashkenazi provided other useful information as well, but all that is important for our purposes is that he clearly identified R. Abraham Kalmankes as a plagiarist. As such, he agreed fully with R. Joseph Samuel’s characterization (in his letter of approbation) of the novice upstart student. The late Professor Gershom Scholem also identified R. Abraham Kalmankes as a plagiarist. He would write:11

והוא [ר'אברהם קלמנקס] הדפיס ס'התחלת חכמה הגניבה [כך כתוב] על שמו,

וכבר יש רמז לדבר בהסכמת הרב מפרנקפורט לס'אשל אברהם.

"He [R. Abraham Kalmankes] published the pirated book entitled Hathalat Hokhmah under his own name. The matter is alluded to in the letter of approbation by the rabbi of Frankfurt to the book entitled Eshel Avraham."

It is our contention that R. Abraham Kalmankes has received less than a fair hearing in the court of modern scholarship. If we reopen the investigation, it is because much of the evidence has either been misconstrued or overlooked. The reader will have to decide for himself whether or not Kalmankes was, in fact, a plagiarist, and whether or not he should be better remembered for his seminal contribution to Jewish teaching and literature.

3. מעין החכמה.

a) Claims of the Author/Editor

מעין החכמה, the first book to appear under R. Abraham Kalmankes’ name, is a short introduction to Lurianic Kabbalah. Indeed, it was among the earliest such works to appear in print. The title page of the quarto sized volume is followed by a one-and-a-half page introduction (pages 2-3). The introduction is followed by the text (pp. 4-22), which consists of 78 tightly-knit chapters (פרקים), perhaps more properly labeled today as paragraphs. Thus, several of the “chapters” consist of no more than15 lines of print (and, sometimes, even less). Scattered throughout the book are occasional comments in parentheses. These may reflect an educational tool used by the original author to clarify a difficult term by means of a gloss, creating -- in effect -- what we would call today a footnote. Or, as appears likely, these may reflect a second hand, i.e., material added to the base text by someone other than the author, e.g., a later editor of the original manuscript. Our immediate concern, however, will not be with the book’s content or structure, but rather with its authorship. What are the claims of the title page and the introduction? What do they tell us about the authorship of

מעין החכמה?

The title page basically announces the content of the book.12 It is a kabbalistic manual, we are informed, the likes of which has yet to appear in print. It provides the kabbalistic underpinning upon which all of R. Isaac Luria’s teachings rest. The title page then indicates that the book’s secret teachings are being brought to press [ Hebrew:תעלומים הוציא לאור] by “the exceedingly wise and young divine kabbalist, R. Abraham, son of the Gaon, Chief Rabbi and Head of the Yeshiva, R. Aryeh Leib, scion of the Kalmankes family of Lublin.” Note that the phrase “being brought to press by” is ambiguous. It is unclear from the title page whether R. Abraham Kalmankes is being presented as the author, editor, or publisher of מעין החכמה.

We perforce turn to the introduction, which – if read carefully – resolves much of the ambiguity of the title page.13The introduction, written and signed by R. Abraham Kalmankes, begins with a justification for the book’s publication. Briefly, Kalmankes, himself a victim and survivor of the Chmielnitzki massacres, informs the reader that he was puzzled by the seemingly endless exile of the Jews, with redemption nowhere in sight. After much reflection – and deeply influenced by kabbalistic teaching – Kalmankes concluded that it was faulty prayer that was prolonging the exile of the Jewish people. Jewish prayer was not piercing the heavens and reaching God on high. He compared the state of the Jewish people to a ship adrift at sea, with no one on board who knows how to steer the ship to safety. Nothing will change, argued Kalmankes, until kabbalistic teaching spreads throughout the Jewish communities. The seeds of redemption were planted by R. Isaac Luria, the master of proper kabbalistic prayer. Alas, he died before redemption set in, but he left a successor, R. Hayyim Vital, who in turn left “a basket full of manuscripts,” i.e. he reduced to writing the kabbalistic teachings of R. Isaac Luria, especially those relating to prayer. Once these teachings were mastered by Jews the world over, redemption would be at hand.

Unfortunately, “the basket full of manuscripts” was not being made available to the Jewish community at large. Kalmankes explains that those who horde the manuscripts refuse to publish them. This, for two reasons. First, for reasons of vanity. By retaining the manuscripts for themselves, they became the masters of esoteric teaching and the power brokers to whom all had to turn for guidance. Second, for reasons of profit. The owners of the manuscripts charged a hefty price for those who wished to view and copy them. Kalmankes decided to put an end to this scandalous state of affairs by acquiring and publishing one of the manuscripts that preserved some of the key esoteric teachings of R. Isaac Luria. Moreover, he “added a few comments of his own, in order to benefit the many readers,” almost certainly a reference to the comments in parentheses mention above. He gave the manuscript a new title, מעין החכמה [Wellspring of Knowledge], for “just as a wellspring begins with a narrow opening that ultimately widens as it fills with water, so too this book begins with nuggets of wisdom that broaden and deepen as one grows in wisdom.” Kalmankes concludes the introduction with the following signature: “These are the words of the youngest

member of the group, Abraham, son of my father and teacher Rabbi Aryeh, son of the Gaon, our teacher and rabbi, the honorable R. Joseph Kalmankes Yaffe of Lublin.”

b) Editions

Some of the confusion surrounding מעין החכמה relates to the multiplicity of published kabbalistic works with the title מעין החכמה, some of which have been mistakenly ascribed to Kalmankes in library catalogues throughout the world.

Confusion surrounding Kalmankes’ alleged plagiarism is also due, in part, to variant readings that appear in the later printed editions of מעין החכמה, for which Kalmankes can hardly be held responsible. After brief mention of some unrelated kabbalistic works with the title מעין החכמה, we will list and describe each of the printed editions of Kalmankes’ מעין החכמה.

An anonymous kabbalistic treatise entitledמעין חכמה (ascribed in part to Moses) is included in the collection entitled ארזי לבנון (Venice, 1601).14 It is unrelated to Kalmankes’ מעין החכמה. The Ashkenazic printing house of the partners Judah Leib b. Mordecai Gimpel and Samuel b. Moses Ha-Levi published yet another anonymous kabbalistic treatise entitled מעין החכמה (Amsterdam, 1651).15 Frequently reprinted, it too is unrelated to Kalmankes’ מעין החכמה.

Four different editions of Kalmankes’ מעין החכמה have appeared in print. They are:

1. מעין החכמה, Amsterdam, 1652. Printed by the Immanuel Beneviste publishing house during the lifetime of its author/editor Abraham Kalmankes, it is the only reliable edition of Kalmankes’ מעין החכמה. As such, we will claim that Kalmankes can be judged only on the basis of this, and no other, edition of מעין החכמה. For a detailed description of the book, its title page, and introduction, see above.16

2. מעין חכמה, Koretz, 1784. This edition was printed by the Johann Anton Krieger publishing house which, in Koretz, was devoted to the publishing of kabbalistic and hasidic works.17 Although Kalmankes’ title of the book is retained, the title page ascribes the book to R. Isaac Luria and makes no mention of Abraham Kalmankes. More importantly, this edition omits Kalmankes’ introduction to the book. The text is a slightly revised and updated version of the Kalmankes edition. It incorporates most of Kalmankes’ parenthetical notes, with slight revision.18 The text was edited in its present form sometime between 1698 and 1784, i.e. well after Kalmankes’ death.19

3. מעיין חכמה, Polonnoye, 1791. Printed by the Samuel b. Yissokhor Baer Segal publishing house, this edition of מעין החכמה appears at the end of a collection of kabbalistic works whose title page reads: ספר הר אדני. מעיין חכמה is accorded no title page of its own. It begins with a skewed version of Kalmankes’ introduction, entitled: הקדמת המחבר ספר מעיין חכמה. No such title is applied to Kalmankes’ introduction in the first edition. We have already indicated (see above) that the introduction is omitted entirely from the second edition, so no such title appears there. The introduction to this, the third edition, closes with the name of the author: אברהם בן מהו'ארי'בן הגאון מה'משה יוסף קלמן מלובלין. In the first edition, however, Kalmankes’ grandfather’s name is given as: הגאון מורנו ורבנא כמוהר"ר יוסף קלמנקס ייפה מלובלין, with no mention of either משה or קלמן. The text that follows is entitled: התחלת החכמה האלהות כפי דרך האר"י אשכנזי ז"ל הנקרא ספר מעיין החכמה. It differs considerably from the text published in the first two editions. It mostly lacks Kalmankes’ parenthetical comments strewn throughout the first two editions. It regularly omits readings that appear in the first two editions, and often adds material that is lacking in the first two editions. Indeed, it is a different manuscript version of the Lurianic digest that was first published by Kalmankes in 1652.20

4. מעין החכמה, Lvov, 1875. No publisher’s name is given. This is a hybrid version drawn from two earlier printed editions. Kalmankes’ introduction is drawn from the skewed version that accompanies the Polonnoye, 1791 edition. The text is drawn from the Koretz, 1784 edition.21 As such, this edition has no independent value and requires no further discussion.

c) Relationship of the Published Editions to the Extant Manuscripts

No one has written more intelligently about the history of Lurianic kabbalistic manuscripts than Yosef Avivi.22 What follows is essentially a brief account of the relationship between the published editions of Kalmankes’מעין החכמה and the extant manuscripts, based largely (but not entirely) upon the results of Avivi’s investigations.

Numerous manuscripts copies of the kabbalistic treatise entitled התחלת החכמה, most of them dating to the 17th and 18th centuries, are extant in libraries throughout Europe, Israel, and the U.S. While they vary slightly from each other, they clearly reflect a single recension of an early 17th century kabbalistic treatise. The anonymous treatise, whose original title is unknown, was written by a disciple of Luria in Damsascus and then sent to Italy. There, the manuscript was copied and circulated under a variety of names such as קונטרס ההיכלות, כללי חכמת שיעור קומה, התחלת החכמה, and התחלת חכמה. It was precisely because a manuscript copy of התחלת חכמה came into the possession of R. Joseph Samuel b. R. Zvi of Cracow sometime prior to 1652, that he was so startled when he saw Kalmankes’ printed edition of מעין החכמה. Even after the printed edition made its debut in 1652, new manuscript copies of the kabbalistic treatise were written and circulated under a variety of titles, now including the title מעין החכמה.

Avivi has shown that the התחלת החכמה manuscripts formed the first part of a larger Lurianic treatise that originally included a second part as well. Whereas the first part focused entirely on עולם האצילות, the second part focused on עולם הבריאה -- and is extant in manuscript form only. The two parts were separated from each other, and largely due to Kalmankes’ publication, the first part became an independent work entitled מעין החכמה. In sum, Kalmankes’ מעין החכמה is an accurate copy (with the addition of occasional glosses by Kalmankes) of an anonymous early 17th century Lurianic treatise that circulated widely under a variety of titles, including the title התחלת החכמה.

4. R. Abraham Kalmankes.

a) Family History

The accusation of plagiarism leveled against R. Abraham Kalmankes by R. Joseph Samuel b. R. Zvi, and seconded by both R. Shmuel Ashkenazi and Gershom Scholem, was not accompanied by any discussion of R. Abraham Kalmankes himself. When and where did he live? How did he make a living? What other books did he author? Was he an inveterate plagiarizer?23 Had such an investigation been conducted, we suspect that the accusation of plagiarism would not have been leveled at all.

In a brief biographical account of Kalmankes published in 1992, the author of the account bemoans the fact that so little is known about Kalmankes’ life history.24 Nonetheless, much more is known about him – and his family -- than the meager snippets of information recorded in the 1992 biographical account or in the standard discussions of מעין החכמה. We will take as our point of departure the clear reference in Kalmankes’ introduction to מעין החכמה to his distinguished grandfather, “the Gaon, our Teacher and our Rabbi, R. Joseph Kalmankes Yaffe of Lublin.” For our purposes, what is most important about the grandfather is that after an illustrious rabbinic career in Lublin, he spent his last years in Prague, where he died, and remains buried to this day.25 The elaborate epitaph on his tombstone informs us that he died at the age of 56 on Sunday,13 Tishre, in the year 5397 (= October 12, 1636).26 The significance of this information will become apparent shortly, but first we need to turn elsewhere.

In 1678, at the family owned printing press in Lublin, R. Abraham Kalmankes published the only other work he would publish in his lifetime. Entitled ספר האשל, it is a masterful (and typical seventeenth century) rabbinic commentary on the book of Genesis.27It was the first installment of a planned commentary on the entire Torah, but apparently the rest of the commentary either never materialized or was never published. The commentary is essentially a midrashic-halakhic work, replete with citations from the Midrash, Talmud, Codes (especially R. Joseph Karo’s שלחן ערוך), and kabbalistic literature. The volume itself is accompanied by a series of letters of recommendations by rabbis from Kremenitz, Lublin, Brisk, Pinsk, Grodno, Vilna,28 and more, all attesting to Kalmankes’ rabbinic scholarship. Once again, Kalmankes prefaced his work with an informative introduction. Kalmankes alludes to the many trials and tribulations that accompanied him through life, including hazardous trips to Egypt and the land of Israel. He was near death on several occasions during his travels, but managed to make his way back safely to Lublin.29 Upon his return, he undertook to publish two works in his lifetime. This, in order to fulfill the talmudic dictum: “Happy is he who arrives here [i.e., on High] with his talmudic teaching in hand.”30 Since according to biblical teaching, a matter is established by “two witnesses,” Kalmankes was determined to author two books and publish them, so that he would have them “in hand” when necessary. The first book, ספר האשל, intended for a more or less popular audience, took the form of a commentary on the book of Genesis. The second book, entitled ברכת אברהם, was intended for talmudic scholars only. Kalmankes informs us that the manuscript copy of ברכת אברהם was completed and that he looked forward to its publication. Sadly, it was never published. What needs to be noted immediately is that Kalmankes never imagined that his earlier publication of מעין החכמה could count as one of his “two witnesses”! (And this was in 1687, long before R. Joseph Samuel b. R. Zvi leveled his accusation of plagiarism in 1701.) Indeed, מעין החכמה is not mentioned at all in Kalmankes’ introduction to ספר האשל. Clearly, he did not consider it a book that he had authored.

Elsewhere in the introduction, Kalmankes notes that he will make a special effort to cite דברי תורה from his grandfather, R. Joseph Kalmankes, who he describes as: "א"א זקני מ"ו הגאון מוהר"ר יוסף קלמנקס, זצ"ל, אשר מנוחתו כבוד בק"ק פראג." Kalmankes adds that upon his grandfather’s death in Prague, all of his writings were lost, and that he – Kalmankes – will therefore record his grandfather’s teachings as he heard them from his disciples. “For,” explains Kalmankes, “I merited to sit at his feet only until the age of ten. Thus, I was a child, and have no real knowledge of his novellae.” We, of course, cannot be certain whether Kalmankes sat at his grandfather’s feet in Lublin or Prague (or both). If only in Prague, and if Kalmankes was ten years old when his grandfather died, we have the latest possible date of birth for Kalmankes, namely 1626, for we have already established that Kalmankes’ grandfather died in 1636. Kalmankes, of course, could have been born earlier than 1626, and we have reason to believe that this was the case.

At the other end of the spectrum, it seems likely that R. Abraham Kalmankes died somewhere between 1678 and 1701. That he was still alive in 1678 is attested by the publication of ספר האשל in that year, and by several of the letters of recommendation dated 1678, all of which describe Kalmankes as alive and well. Since Kalmankes never responded to the devastating accusation of plagiarism made against him in 1701 by a leading rabbinic contemporary, it is probably safe to assume that he died before the accusation appeared in print. Though we cannot pinpoint the year of his death with precision, the most likely candidates are either 1692 or 1693. Kalmankes died in Lvov, where he served on its rabbinic court as דיין.31 The text of the epitaph on his tombstone was copied and published in 1863 and reads:32

ביום טוב נהפך כי טוב פעמים ואבל ומספד ונהי בכפלים

ט"ו בחודש ניסן נגנז צנצנת המן המאיר באספקלריא המאירה

כבוד מורינו ורבנו ומאורנו נתבקש בישיבה של מעלה

הגאון האלוף עין הגולה מו"ה אשר יעקב אברהם בן הרב מוהר"ר אריה קלמנקש

צלל במים אדירים של תורה וחיבר ס'אשל אברהם על שמו נקרא

ובשביל שזיכה את הרבים יבוא שלום וינוח על משכבו בשלום

Thus, Kalmankes died on 15 Nisan on a Tuesday.33 But in which year? The text states unequivocally that it was in the year whose numerical value was embedded in the biblical phrase תתן אמת ליעקב.34 But the copyist (in 1863) informed his readers that, due to an erasure, he could no longer determine which letters from the phrase were enlarged or highlighted on the original tombstone. This makes it difficult, but not impossible – as we shall see – to calculate Kalmankes’ approximate year of death. Since Kalmankes died on the first day of Passover which fell on a Tuesday, seven candidates (between the years 1678 and 1701) present themselves: 1679, 1686, 1689, 1692, 1693, 1696, and 1699. The Hebrew equivalents for these years are: [5]439, [5]446, [5]449, [5]452, [5]453, [5]456, and [5]459. Now the numerical value of a combination of letters from the phrase תתן אמת ליעקב must add up exactly to one or more of the above Hebrew dates. Only two solutions are possible: [5]45235 and [5]453.36 These are 1692 and 1693, respectively.37 In sum, if we had to give mostly approximate dates for the three generations of the Kalmankes family mentioned by R. Abraham Kalmankes in both of his publications, they would be:

R. Joseph Kalmankes: 1580-1636

R. Aryeh Kalmankes: 1600-167038

R. Abraham Kalmankes: 1620-169339

b) Citation from מעין החכמה in ספר האשל

Critical for our discussion is the fact that R. Abraham Kalmankes cites מעין החכמה in his ספר האשל!40 It is the only reference to מעין החכמה in ספר האשל.The passage reads:41

או יאמר מאמר הר"י ז"ל באשר נקדים מאמר מהאר"י לור"י[א] הנזכר בספר מעיין החכמה

אשר הביאותיו לבית הדפוס בפ'י"ד שבשעת הבריאה...

Or we can explain this by citing a passage from R. Isaac of blessed memory, i.e., by first introducing a passage by R. Isaac Luria Ashkenazi -- which is mentioned in chapter 14 of the book מעיין החכמה, which I brought to press [literally: to the publishing house] -- which states that during the period of creation…

If one examines chapter 14 of מעין החכמה, the passage cited by Kalmankes in ספר האשל appears exactly as referenced, but Luria’s name appears nowhere in the text of chapter 14! This is precisely because מעין החכמה was a repository of Lurianic teaching which he – Kalmankes – brought to press. Kalmankes never claimed authorship of the book, and he tells us so in his own words in 1678, long before any accusation was leveled against him.

5. Conclusions.

Ultimately, whether or not Kalmankes is viewed as a plagiarist will depend largely on one’s definition of plagiarism.42 In terms of literary (as distinct from oral) plagiarism, a reasonable definition would seem to be:

Plagiarism is the act of appropriating in print another person’s ideas, writings, or words, and passing them off as one’s own by not providing proper attribution to their original source.

Even aside from the definition itself, the moral opprobrium attached to any specific act of plagiarism will depend on a variety of factors. Thus, it seems to me, that the more literal and lengthy the borrowing, the more heinous the offense. Motive too will surely play a role in determining the severity of the offense. We turn to the specifics of the Kalmankes case.

One can certainly sympathize with R. Joesph Samuel’s outrage when, in the 1650’s, he chanced upon a copy of the recently published מעין החכמה. He leafed through its pages and realized instantaneously that it was virtually word for word a printed copy of a manuscript he owned under the title התחלת חכמה. Worse yet, prominently displayed on the title page of the pirated book was the name of the “divine kabbalist,” R. Abraham Kalmankes, a name otherwise unknown to R.Joseph Samuel. He could only conclude that this was a blatant case of plagiarism that called for condemnation. Indeed, he was still upset about the matter some fifty years later!

But, as we have seen, the title page of מעין החכמה is somewhat ambiguous about Kalmankes’ role in its authorship and publication. It simply states that Kalmankes הוציא לאור the תעלומים, i.e., he published the secret or hidden digest of Lurianic teaching. One suspects that R. Joseph Samuel never examined Kalmankes’ introduction to מעין החכמה. Had he done so, he surely would have noticed that Kalmankes admits openly that he is publishing a manuscript that contains a digest of Lurianic teaching, authored by a disciple of Luria – and not by him. Kalmankes’ states unequivocally that his contribution to the volume is limited to the few comments he added (almost always in parentheses) and to the new title, מעין החכמה, he provided for it. It is only in the third edition of מעין החכמה, published in Polonnoye, 1791 – long after Kalmankes’ death – that a skewed version of Kalmankes’ introduction is labeled: הקדמת המחבר ספר מעיין חכמה, in effect suggesting that Kalmankes was the author of מעין החכמה. Anyone who reads this skewed version of Kalmankes’ introduction, and compares it to the original, will realize at once that it is was created in 1791 in order to harmonize its content with that of a different manuscript version of the Lurianic digest (one that lacked Kalmankes’ comments) that was being attached to it.43

We have also the clear evidence from Kalmankes’ introduction to ספר האשל, published by him in 1678, that he sought to author and publish two books in his lifetime, so as not to be embarrassed when he was called “on High.” He provides the titles of both books, yet makes no mention of the fact that he had authored and published a book called מעין החכמה. He knew full well that this was a book written by others, which he had brought to press. Indeed, as we have seen, he cited מעין החכמה in his ספר האשל. When doing so, he stated openly that it was a Lurianic work that he had brought to press.

There doesn’t seem to be much evidence here for plagiarism, as defined above. Kalmankes’ מעין החכמה was based upon a Lurianic manuscript that was anonymous and was circulating under a variety of titles. Kalmankes never claimed authorship of the manuscript, and indicated clearly that all he did was to provide the manuscript with a new title and some brief annotation. This he did for the best of motives, namely to bring about the ultimate redemption of the Jewish people. He did not pass off the work as his own (other than the title and the annotations, which were legitimately his own creation); he withheld no proper attribution.

On the other hand, three distinguished scholars, R. Joseph Samuel of the seventeenth century, and R. Shmuel Ashkenazi and the late Professor Gershom Scholem of the twentieth century, were persuaded that Kalmankes was a plagiarist. Perhaps they felt that the appearance of Kalmankes‘ name on the title page of מעין החכמה, preceded by the words "אב בחכמה ורך בשנים המקובל האלוהי כמוהר"ר,” with no mention of any manuscript or attribution to others, was sufficiently misleading – and, perhaps, even deliberately intended – to create the impression that Kalmankes was the author of the book. If so, they would argue, he deserves to be listed among the plagiarizers. I am not persuaded that this is the case, but in deference to the three distinguished scholars mentioned above, I have allowed the title of this essay to read as it does. At best (or: worst), it is a mild case of plagiarism, if even that.44

NOTES

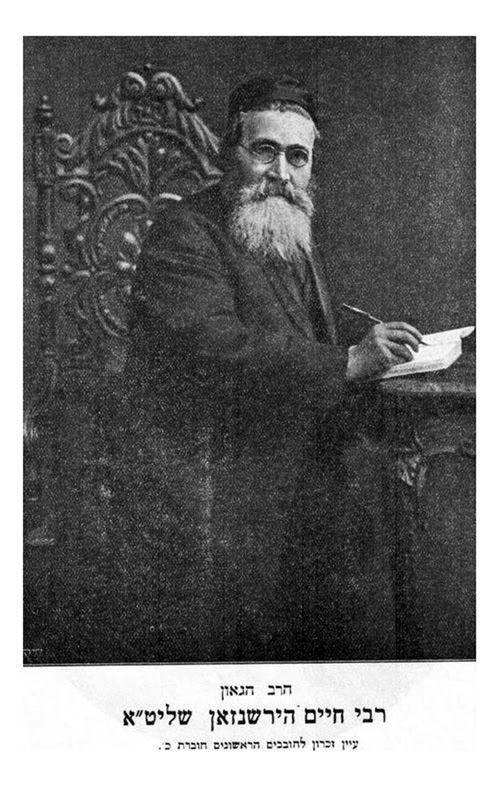

1 For biographical studies of R. Joseph Samuel b. R. Zvi, see H.N. Dembitzer,

כלילת יופי (Cracow, 1893), vol. 2, pp. 144b-152b; M. Horovitz, Frankfurter Rabbinen (Jerusalem, 1969), ed. J. Unna, pp. 94-97 and 296-297; and idem,

רבני פרנקפורט (Jerusalem, 1972), ed. J. Unna, pp. 67-69 and 212. For the epitaph on his tombstone, see idem, אבני זכרון (Frankfurt, 1901), p. 151. For legendary accounts of R. Joseph Samuel, see E. Sternhell, ",תולדות יצחק" p. 2b, in Y.I. Billitzer, באר יצחק (Paks, 1898); and Y.L. Maimon, שרי המאה (Jerusalem, 1955), vol. 1, pp. 231-233.

2 For an assessment of R. Joseph Samuel’s contribution to the printed text of the Talmud, see Y. S. Spiegel, עמודים בתולדות הספר העברי: הגהות ומגיהים (Ramat-Gan, 2005), second edition, pp. 404-407.

3 See L. Loewenstein, מפתח ההסכמות (Lakewood, 2008), ed. S. Eidelberg, pp. 99-100.

4 H.N. Dembitzer, op. cit., vol. 2, p. 150a.

5 See G. Scholem, חלומותיו של השבתאי ר'מרדכי אשכנזי (Jerusalem, 1938); and Y. Tishby, נתיבי אמונה ומינות (Jerusalem, 1964), pp. 81-107. Cf. the historical vignette in Rabbi P. Katzenellinbogen, יש מנחילין (Jerusalem, 1986), ed. Y.D. Feld, pp. 74-75.

6 The original reads:

ושתים רעות עושים כי לא ידעו ולא יבינו אל פעולות השם, גם גורמים להשניא בעיני המון את חכמי תורה שבנגלה, כסבורים העם דמאן דלא ידע האי לאו גברא רבה הוא, ומשליכים אחרי גיום חכמים חרשים ושומעים לקול מלחשים, אשר בטליתות שאינן שלהם מלבשים, כאשר בקושטא קא אמינא בדידי הוה עובדא, נהירנא זה חמישים שנה שבידי ספר נחמד כתוב על חכמת הקבלה נקרא תחלת חכמה, והנה קם מאן דהו תלמיד חדש שישן אין בו והדפיסו על שמו, והנה גנוב הוא אתו.

7 A. Schischa, “שלושה ספרים נעלמים,” עלי ספר 2(1976), pp. 237-240.

8 S. Ashkenazi, “שתי הערות,” עלי ספר 3(1976), pp. 171-173. For an expanded version of Ashkenazi’s comments in עלי ספר, see his אסופה: ארבעה מאמרים מאוצרות הר"ש אשכנזי שליט"א (Jerusalem, 2014), pp. 49-53. Cf. S.Z. Havlin, “הערת העורך,” עלי ספר 11(1984), p. 134.

9 These include the National Library in Jerusalem, the Bodleian Library at Oxford, and a host of other libraries in Europe and the United States. For an early description of two such manuscripts in the National Library in Jerusalem, see G. Scholem, כתבי יד בקבלה (Jerusalem, 1930), p. 63, manuscript 2512, and p, 117, manuscript 47. The Bodleian Library lists some 10 manuscript copies of התחלת חכמה in its collection. See A. Neubauer, Catalogue of the Hebrew Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library and in the College Libraries of Oxford (Oxford, 1886), column 1001. Cf. the corrections to these listings in M. Beit-Arie and R.A. May, eds., Catalogue of the Hebrew Manuscript in the Bodleian Library: Supplement of Addenda and Corrigenda (Oxford, 1994), passim. A manuscript copy of התחלת חכמה was in the private library of R. Joseph Solomon Delmedigo in 1631. See his נובלות חכמה (Basel, 1631), p. 195a. The precise title of the book varies in the manuscripts, with the most common titles being התחלת חכמה and

התחלת החכמה.

10 See L. Fuks and R.G. Fuks-Mansfeld, Hebrew Typography in the Northern Netherlands 1585-1815 (Leiden, 1984), vol. 1, pp. 176-177, entry 233.

11 See the undated loose page, in Scholem’s hand, appended to Scholem’s copy of מעין חכמה at the National Library in Jerusalem. Cf. ספריית גרשם שלום בתורת הסוד היהודית: קטלוג (Jerusalem, 1999), vol. 1, p. 312, entry 4188.

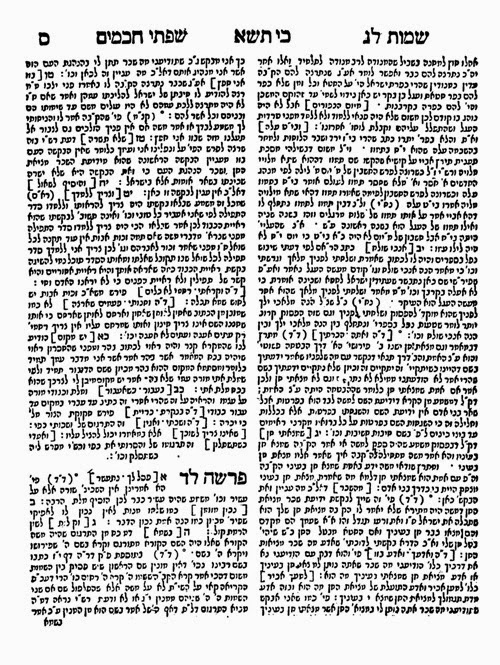

12 See the scan of the title page.

![]()

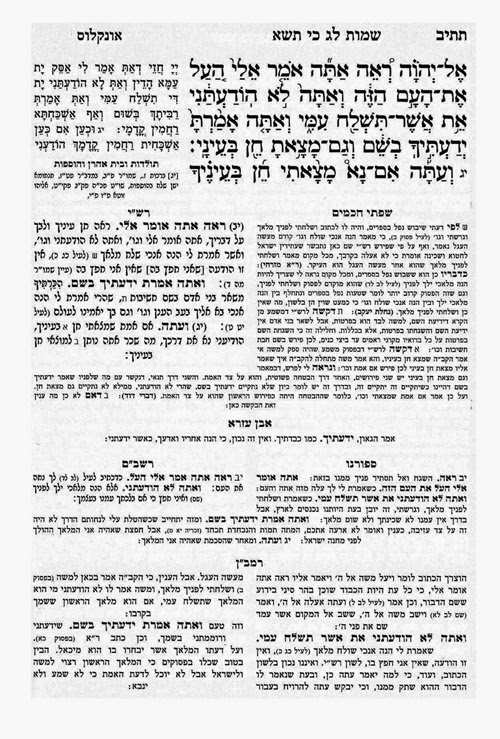

13 See the scan of the introduction.

14 The title is so listed on the pages of the treatise itself in ארזי הלבנון, pp. 46b-47a. On the title page of ארזי הלבנון, it is listed as מעיין החכמה. The frequent and easy interchange between the spellings מעין and מעיין and the spellings חכמה and החכמה characterizes virtually all the printed editions of the various books bearing these titles.

15 L. Fuks and R.G. Fuks-Mansfeld, op. cit., vol. 1, p. 195, entry 270,

16 Only a handful of copies are extant world wide. To the best of my knowledge, the first edition of Kalmankes’

מעין החכמה has not been photo-mechanically reproduced, and it is not available online (as of the date this note was recorded). Nor is it available on any of the standard electronic collections of rabbinic literature, such as HebrewBooks,

אוצר החכמה, or

אוצרות התורה. I am indebted to the National Library in Jerusalem and the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York for making their copies available to me. The scans of the title page and the introduction are reproduced here courtesy of the Bibliotheca Rosenthalia, now in the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam (online catalogue:

http://permalink.opc.uva.nl/item/001748453).

17 H. D. Friedberg, תולדות הדפוס העברי בפולניא (Antwerp, 1932), p. 61.

18 One key revision appears on p. 1, chapter 2, where ספר ויקהל משה is referenced. The book is not mentioned in the first edition of Kalmankes’ מעין החכמה, nor could it have been, since ספר ויקהל משה was not published until 1698. The reference is to R. Moshe Graf, ויקהל משה (Dessau, 1698). It does not appear likely that Kalmankes saw Graf’s work in manuscript form, since מעין החכמה was published in 1652 and Graf was born in 1650.

19 For the date of Kalmankes’ death, see below. The Koretz, 1784 edition was photo-mechanically reproduced in Jerusalem, 1970.

20 The Polonnoye, 1791 edition of מעיין חכמה was photo-mechanically reproduced in Jerusalem, n.d. (circa 1998), in a thin, dark blue, hardbound volume whose spine and outer cover read צדיק יסוד עולם, and whose title page reads הר אדני. (In other words, when seeking a copy in a bookshop of the reprint of the Polonnoye, 1791 edition of מעיין חכמה, whatever else you do, don’t ask for a copy of מעיין חכמה.)

21 As noted by S. Ashkenazi (see above, note 8), the title page of the Lvov edition indicates that its text is based upon the Koretz edition, and reproduces the very biblical phrase used by the Koretz edition for indicating its original date of publication in 1784. But by highlighting a different set of letters within the same biblical phrase, the Lvov edition announces to the reader that its date of publication is 1875.

22 Y. Avivi, קבלת האר"י (Jerusalem, 2008), 3 volumes, passim. See especially vol. 1, pp. 204-208, 443; and vol. 2, pp. 565-568, 840-841. See also, idem, “כתבי האר"י באיטליה עד שנת ש"פ",” עלי ספר 11(1984), pp. 91-134; and “הערה,” עלי ספר 12(1986), p. 133.

23 “Plagiarism is something people may do for a variety of reasons but almost always something they do more than once.” So T. Mallon, Stolen Words: Forays into the Origins and Ravages of Plagiarism (New York, 1989), preface, p. xiii.

24 Rabbi M.Y.S. Goldenberg, “פתח דבר,” to the reissue of R. Abraham Kalmankes’ ספר האשל (Brooklyn, 1992).

25 On R. Joseph Kalmankes Yaffe of Lublin, see J. Kohen-Zedek, שבת אחים ( St. Petersburg, 1898), pp. 59-76; S. B. Nissenbaum, לקורות היהודים בלובלין, (Lublin, 1920), second edition. pp. 36-37; S. Buber, אנשי שם (Cracow, 1895), p. 89, entry 217; and S. Englard, “צפונות יוחסין (א), “ ישורון 3(1997), p. 680, note 6 and p. 694, note 36a.

26 See K. Lieben, גל עד (Prague, 1856), German section, p. 46; Hebrew section, pp. 34-35.

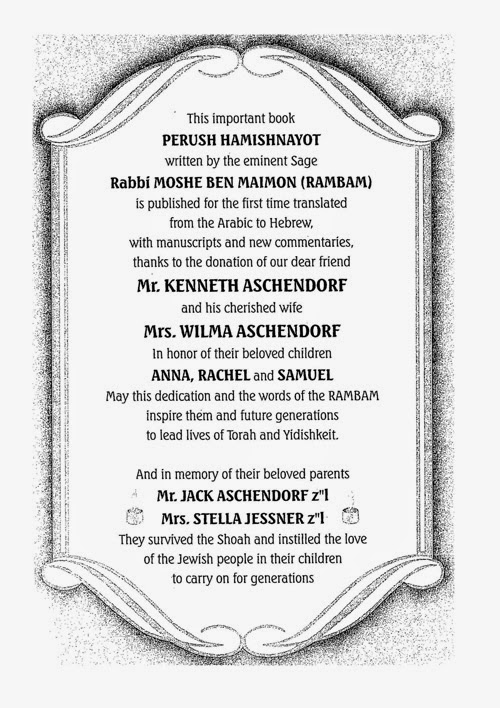

27 R. Abraham Kalmankes, ספר האשל (Lublin, 1678). Few copies have survived. For the copy at the Bodleian Library, see M. Steinschneider, Catalogus Librorum Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana (Berlin, 1860), vol. 1, column 752, entry 4458:1; and A.E. Cowley, A Concise Catalogue of the Hebrew Printed Books in the Bodleian Library (Oxford, 1929), p. 45. For the copy at the British Library, see J. Zedner, Catalogue of the Hebrew Books in the British Museum (London, 1867), p. 14. For the copy at Yeshiva University’s Mendel Gottesman Library, see B. Strauss, אהל ברוך (London, 1959), p. 31, entry 534. To the best of my knowledge, the first edition of Kalmankes’ ספר האשל has not been photo-mechanically reproduced, and is it not available online (as of the date this note was recorded). Nor is it available on any of the standard electronic collections of rabbinic literature, such as HebrewBooks, אוצר החכמה, or אוצרות התורה. A new edition of this exceedingly rare volume was made available by Rabbi M.Y.S. Goldenberg (Brooklyn, 1992) and we are indebted to him. Nonetheless, one needs to use this new edition with caution; the text has been “improved” for the modern reader. A comparison of the texts of the title page, as they appeared in 1678 and 1992, serves as an indicator of the occasional liberties taken with the text. A seemingly enigmatic woodcut (opposite the opening page of the commentary on Genesis) depicting a Jew (Kalmankes?) drawing water from a well (מעין החכמה?) – and framed in an elaborate frame marked by two angelic beings holding up a crown inscribed with the words כתר תורה – was not reproduced in the 1992 edition. See the attached scans:

28 The letter of recommendation from Vilna, dated 1673, was written by its Chief Rabbi, R. Moses b. David Kramer (d. 1687), the paternal great-great-grandfather of the Vilna Gaon.

29 These vicissitudes of life may account for the additional first names of Kalmankes, who in ספר האשל is identified as אשר יעקב אברהם קלמנקס. For the practice of changing names and/or adding additional first names when confronted by difficult circumstances, see R. Judah He-Hasid, ספר חסידים (Jerusalem, 1957), ed. R. Margulies, p. 214, paragraph 245 and notes. Cf. A. Teherani, כתר שם טוב (Jerusalem, 2000), vol. 1, pp. 293-315.

30 B. Pesahim 50a and parallels.

31 S. Buber, op. cit., p. 45, entry 101.

32 G. Suchestow, מצבת קודש (Lemberg, 1863), second edition, vol. 1, no pagination, entry 32.

33 The opening line ביום טוב נהפך כי טוב פעמים signals that Kalmankes died on a holiday that fell on the day when כי טוב was said twice. The next line identifies the holiday as 15 Nisan, i.e., the first day of Passover. The day כי טוב was said twice refers, of course, to the third day of creation, i.e. Tuesday. See Gen. 1:10 and 12.

34 Buber, loc. cit., writes with confidence that the highlighted letters are אמ"ת, which would indicate that Kalmankes died in [5]441 or 1681. But in 1681, the first day of Passover fell on a Thursday, not on a Tuesday. Suchestow was more circumspect, indicating it was no longer possible to determine which of the engraved letters were enlarged or highlighted. He left the problem unresolved. The usual practice for highlighting was the placement of a protruding dot over the engraved letters that were to be used for reckoning the year of death. The problem cannot be resolved by emending the second line to read ט"ז בחודש ניסן instead of ט"ו בחודש ניסן, since the second day of Passover can never fall on a Tuesday. See שלחן ערוך, אורח חיים, סימן תכח: א.

35 By highlighting the letters תתן אמ'ת'לי'עקב'.

36 By highlighting the letters תתן א'מ'ת' לי'עקב'.

37 These dates are based upon the assumption that the text of Kalmankes’ epitaph, as copied and published by Suchestow in 1863, is an accurate copy of the original. But this may not be the case. Suchestow’s מצבת קודש is marred by egregious errors. He sometimes copied and published as many as four different versions of the same epitaph! In another instance, he divided an epitaph into two parts, creating two dead persons when only one was called for. See the critiques of Suchestow in S. Buber, op. cit. (above, note 25), pp. vi-viii and in R. Margulies, “",לתולדות אנשי שם סיני 26(1949-50), p. 113 ( and throughout the later installments to this essay published in סיני between 1950 and 1952). Given that Kalmankes’ tombstone was close to 200 years old when it was copied in 1863, it is likely that the epitaph could be read only with great difficulty. While any attempt at emending the received text is speculative, a slight emendation of the first lines of the epitaph yields the following text:

שנת תתן אמ"ת ליעקב

ביום טוב נהפך טוב פעמים ואבל ומספד ונהי בכפלים

ט"ו בחודש ניסן נגנז צנצנת המן המאיר באספקלריא המאירה

The sense would be that Kalmankes died on 15 Nisan, on יום טוב, on a day when טוב was twice overturned. It was overturned first, because every day of the week of creation was described as טוב(with the exception of the second and seventh days); and second, because it was יום טוב, a holiday. This would allow for 15 Nisan to fall on a Thursday, and indeed in 1681 (the numerical equivalent of אמ"ת), the first day of Passover fell on a Thursday. If so, Kalmankes may well have died in 1681.

38 These dates are an approximation. We know only that R. Aryeh Kalmankes died in 1671 or earlier, as his name appears with ברכת המתים in several letters of approbation dated 1671 and appended to ספר האשל.

39 These dates, as well, are an approximation. For possible evidence that R. Abraham Kalmankes died in 1681, see above, note 37. If Kalmankes was born in 1620, he would have been 32 years old when מעין החכמה was published in 1652. This fits well with his description on its title page as a רך בשנים. It also fits well with R. Joseph Samuel’s characterization of him (at the time) as an “upstart student.” It would also mean that he was nearing 60 years of age in 1678, when he published ספר האשל. This fits well with his bemoaning the fact – in the introduction to the volume – that the hair on his head and beard had turned gray and that old age was overtaking him.

40 It is astonishing that the author of the most comprehensive study of the Kalmankes family, J. Kohen-Zedek, שבת אחים (see above, note 25), concluded on pp. 67-68, that the authors of מעין החכמה and ספר האשל were two different people named Kalmankes (cousins, of course)! Among his proofs is the alleged fact that the author of ספר האשל was unaware of the existence of מעין החכמה. Alas, Kohen-Zedek overlooked the passage cited here. So too Gershom Scholem, who wrote: "המחבר [של ספר מעין החכמה] לא הזכיר את הספר בספריו הוא, כגון ספר האשל." See the loose page in Scholem’s hand and the Scholem Library Catalogue, referred to above, note 11. Scholem, however, did not conclude with Kohen-Zedek that the authors of מעין החכמה and ספר האשל were two different people. Even more astonishing is the fact that the late bibliophile, R. Reuven Margulies, cited Kohen-Zedek’s conclusion approvingly. See R. Margulies, “לתולדות אנשי שם בלבוב,” סיני 26(1949-50), p. 219. It appears likely that Scholem (in part) and Margulies were misled by Kohen-Zedek.

41 ספר האשל (Lublin, 1678), p. 8b. We have printed the text as it appears

in the first edition. In the 1992 edition, it appears on p. 29 as follows:

או יאמר באשר נקדים מאמר הר"י לוריא הנזכר בספר מעיין החכמה אשר הביאותיו לבית הדפוס בפ'י"ד, שבשעת הבריאה...

42 In general, see A. Lindey, Plagiarism and Originality (New York, 1952); T. Mallon, op. cit. (above, note 23); and J. Anderson, Plagiarism, Copyright Violation and Other Thefts of Intellectual Property: An Annotated Bibliography with a Lengthy Introduction (Jefferson, North Carolina, 1998).

43 Thus, in the introduction to the first edition of מעין החכמה, Kalmankes states:

וגם מעט מזער מדעתי הוספתי אך לזכות הרבים היא כוונתי (I added but a few comments of my own; my only intention is to benefit the many). In the Polonnoye, 1791 edition this was radically changed to: וגם מעט מזער מדעתי לא הוספתי אך לזכות הרבים היא כוונתי (I added not even the fewest of comments of my own; my only intention is to benefit the many). This change was made necessary because the kabbalistic manuscript now appended to Kalmankes’ introduction, and being published together with it for the first time, did not contain Kalmankes’ additional comments.

44 I am deeply grateful to Rabbi Menachem Silber for reading and commenting on an earlier draft of this essay. The errors that remain are entirely mine.

,_title_page_small.jpg)

_title_page_small.jpg)

,_introduction,_p._2a_small.jpg)

,_intoduction,_p._2b_small.jpg)

,_woodcut_small.jpg)

,_title_page_small.jpg)

,_title_page_small.jpg)