The Identity and Meaning of Chashmonai [1]

By Mitchell First (MFirstatty@aol.com)

The name Chashmonai appears many times in the Babylonian Talmud, but usually the references are vague. The references are either to beit Chashmonai, malkhut Chashmonai, malkhut beit Chashmonai, malkhei beit Chashmonai, or beit dino shel Chashmonai.[2] One time (at Megillah 11a) the reference is to an individual named Chashmonai, but neither his father nor his sons are named.

The term Chashmonai (with the spelling חשמוניי) appears two times in the Jerusalem Talmud, once in the second chapter of Taanit and the other in a parallel passage in the first chapter of Megillah.[3] Both times the reference is to the story of Judah defeating the Syrian military commander Nicanor,[4] although Judah is not mentioned by name. In the passage in Taanit, the reference is to echad mi-shel beit Chashmonai.[5] In the passage in Megillah, the reference is to echad mi-shel Chashmonai. Almost certainly, the passage in Taanit preserves the original reading.[6] If so, the reference is again vague.

Critically, the name Chashmonai is not found in any form in I or II Maccabees, our main sources for the historical background of the events of Chanukkah.[7] But fortunately the name does appear in two sources in Tannaitic literature.[8]It is only through one of these two sources that we can get a handle on the identity of Chashmonai.

------------

Already in the late first century, the identity of Chashmonai seems to have been a mystery to Josephus. (Josephus must have heard of the name from his extensive Pharisaic education, and from being from the family.) In his Jewish War, he identifies Chashmonaias the father of Mattathias.[9] Later, at XII, 265 of his Antiquities, he identifies Chashmonai as the great-grandfather of Mattathias.[10] Probably, his approach here is the result of his knowing from I Maccabees 2:1 that Mattathias was the son of a John who was the son of a Simon, and deciding to integrate the name Chashmonai with this data by making him the father of Simon.[11]It is very likely that Josephus had no actual knowledge of the identity of Chashmonaiand was just speculating here. It is too coincidental that he places Chashmonaias the father of Simon, where this room for him. If Josephus truly had a tradition from his family about the specific identity of Chashmonai, it would already have been included in his Jewish War.

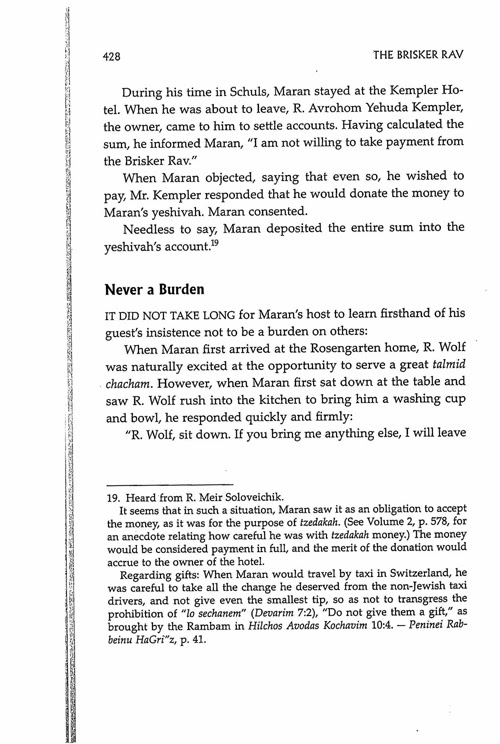

The standard printed text at Megillah 11a implies that Chashmonai is not Mattathias: she-he-emadeti lahem Shimon ha-Tzaddik ve-Chashmonai u-vanav u-Matityah kohen gadol…This is also the implication of the standard printed text at Soferim 20:8, when it sets forth the Palestinian version of the Amidah insertion for Chanukkah; the textincludes the phrase: Matityahu ben Yochanan kohen gadol ve-Chashmonai u-vanav...[12] There are also midrashim on Chanukkah that refer to a Chashmonai who was a separate person from Mattathias and who was instrumental in the revolt.[13]

But the fact that I Maccabees does not mention any separate individual named Chashmonaiinvolved in the revolt strongly suggests that there was no such individual. Moreover, there are alternative readings at both Megillah 11a and Soferim20:8.[14] Also, the midrashim on Chanukkah that refer to a Chashmonai who was a separate person from Mattathias are late midrashim.[15] In the prevalent version of Al ha-Nissimtoday, Chashmonai has no vavpreceding it.[16]

If there was no separate person named Chashmonai at the time of the revolt, and if the statement of Josephus that Chashmonai was the great-grandfather of Mattathias is only a conjecture, who was Chashmonai?

Let us look at our two earliest sources for Chashmonai. One of these is M. Middot 1:6.[17]

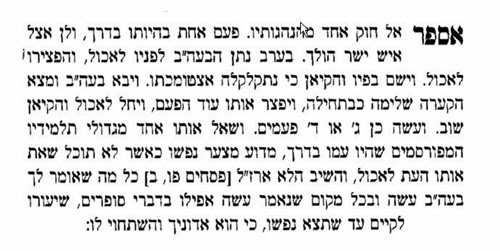

…המוקדבביתהיולשכותארבע

[18]…ייוןמלכיששיקצוםהמזבחאבניאתחשמונייבניגנזובהצפוניתמזרחית

From here, it seems that Chashmonai is just another name for Mattathias. This is also the implication of Chashmonai in many of the later passages.[19]

The other Tannaitic source for Chashmonaiis Seder Olam, chap. 30. Here the language is: malkhut beit Chashmonai meah ve-shalosh =the dynasty of the House of Chashmonai, 103 [years].[20] Although one does not have to interpret Chashmonaihere as a reference to Mattathias, this interpretation does fit this passage.

Thus a reasonable approach based on these two early sources is to interpret Chashmonai as another way of referring to Mattathias.[21] But we still do not know why these sources would refer to him in this way. Of course, one possibility is that it was his additional name.[22] Just like each of his five sons had an additional name,[23]perhaps Chashmonai was the additional name of Mattathias.[24] But I Maccabees, which stated that each of Mattathias’ sons had an additional name, did not make any such statement in the case of Mattathias himself.

Perhaps we should not deduce much from this omission. Nothing required the author of I Maccabees to mention that Mattathias had an additional name. But one scholar has suggested an interesting reason for the omission. It is very likely that a main purpose of I Maccabees was the glorification of Mattathias in order to legitimize the rule of his descendants.[25] Their rule needed legitimization because the family was not from the priestly watch of Yedayah. Traditionally, the high priest came from this watch.[26] I Maccabees achieves its purpose by portraying a zealous Mattathias and creating parallels between Mattathias and the Biblical Pinchas, who was rewarded with the priesthood for his zealousness.[27]Perhaps, it has been suggested, the author of I Maccabees left out the additional name for Mattathias because it would remind readers of the obscure origin of the dynasty.[28](We will discuss why this might have been the case when we discuss the meaning of the name in the next section.)

-----

We have seen that a reasonable approach, based on the two earliest rabbinic sources, is to interpret Chashmonai as another way of referring to Mattathias.

The next question is the meaning of the name. The name could be based on the name of some earlier ancestor of Mattathias. But we have no clear knowledge of any ancestor of Mattathias with this name.[29] Moreover, this only begs the question of where the earlier ancestor would have obtained this name.[30] The most widely held view is that the name Chashmonai derives from a place that some ancestor of Mattathias hailed from a few generations earlier. (Mattathias and his immediate ancestors hailed from Modin.[31]) For example, Joshua 15:27 refers to a place called Cheshmon in the area of the tribe of Judah .[32]Alternatively, a location Chashmonah is mentioned at Numbers 33:29-30 as one of the places that the Israelites encamped in the desert.[33] In either of these interpretations, the name may have reminded others of the obscure origin of Mattathias’ ancestors and hence the author of I Maccabees might have refrained from using it.

It has also been observed that the word חשמנים (Chashmanim) occurs at Psalms 68:32:

.לאלקיםמני מצרים; כוש תריץ ידיוחַשְׁמַנִּיםיאתיו

Chashmanimwill come out of Egypt; Kush shall hasten her hands to God.

(The context is that the nations of the world are bringing gifts and singing to God.[34])

It has been suggested that the name Chashmonaiis related to חשמניםhere.[35] Unfortunately, this is the only time the word חשמנים appears in Tanakh, so its meaning is unclear.[36] The Septuagint translates it as πρέσβεις (=ambassadors).[37] The Talmud seems to imply that it means “gifts.”[38] Based on a similar word in Egyptian, the meanings “bronze,” “natron” (a mixture used for many purposes including as a dye), and “amethyst” (a quartz of blue or purplish color) can be suggested.[39] Ugaritic and Akkadian have a similar word with the meaning of a color, or colored stone, or a coloring of dyed wool or leather; the color being perhaps red-purple, blue, or green.[40] Based on this, meanings such as red cloth or blue cloth have been suggested.[41] Based on similar words in Arabic, “oil” and “horses and chariots” have been proposed.[42] A connection to another hapax legomenon, אשמנים,[43]has also been suggested. אשמנים perhaps means darkness,[44] in which case חשמנים, if related, may mean dark-skinned people.[45]Finally, it has been suggested thatחשמנים derives from the word שמן (oil), and that it refers to important people, i.e., nobles, because the original meaning is “one who gives off light.” (This is akin to “illustrious” in English).[46]

But the simplest interpretation is that it refers to a people by the name חשמנים.[47] An argument in favor of this is that חשמנים seems to be parallel to Kush, another people, in this verse. Also, יאתיוis an active form; it means “will come,” and not “will be brought.”[48]

Whatever the meaning of the word חשמנים, I would like to raise the possibility that an ancestor of Mattathias lived in Egypt for a period and that people began to call him something like Chashmonai upon his return, based on this verse.

Conclusions

Even though Josephus identifies Chashmonaias the great-grandfather of Mattathias, this was probably just speculation. It is too coincidental that he places Chashmonai as the father of Simon, precisely where this room for him.

The most reasonable approach, based on the earliest rabbinic sources, is to interpret Chashmonaias another way of referring to Mattathias, either because it was his additional name or for some other reason. A main purpose of I Maccabees was the glorification of Mattathias in order to legitimize the rule of his descendants. This may have led the author of I Maccabees to leave the name out; the author would not have wanted to remind readers of the obscure origin of the dynasty.

Most probably, the name Chashmonaiderives from a place that some ancestor of the family hailed from.

-----

A few other points:

º Most probably, the name חשמונאי did not originally include an aleph. The two earliest Mishnah manuscripts, Kaufmann and Parma (De Rossi 138), spell the name חשמוניי.[49]This is also how the name is spelled in the two passages in the Jerusalem Talmud.[50]As is the case with many other names that end with אי (such as שמאי), the aleph is probably a later addition that reflects the spelling practice in Babylonia.[51]

º The plural חשמונאים is not found in the rabbinic literature of the Tannaitic or Amoraic periods,[52]and seems to be a later development.[53] (An alternative plural that also arose is חשמונים; this plural probably arose earlier than the former.[54]) This raises the issue of whether the name was ever used in the plural in the Second Temple period.

The first recorded use of the name in the plural is by Josephus, writing in Greek in the decades after the destruction of the Temple.[55] It is possible that the name was never used as a group name or family name in Temple times and that we have been misled by the use of the plural by Josephus.[56] On the other hand, it is possible that by the time of Josephus the plural had already come into use and Josephus was merely following prevailing usage. In this approach, how early the plural came into use remains a question.

Since there is no evidence that the name was used as a family or group name at the time of Mattathias himself, the common translation in Al ha-Nissim: “the Hasmonean” (see, e.g.,the Complete ArtScroll Siddur, p. 115) is misleading. It implies that he was one of a group or family using this name at this time. A better translation would be “Chashmonai,” implying that it was a description/additional name of Mattathias alone.

° The last issue that needs to be addressed is the date of Al ha-Nissim.

According to most scholars, the daily Amidahwas not instituted until the time of R. Gamliel, and even then the precise text was not fixed.[57] Probably, there was no Amidah at all for most of the Second Temple period.[58] The only Amidot that perhaps came into existence in some form in the late Second Temple period were those for the Sabbath and Biblical festivals.[59]Based on all of the above, it is extremely unlikely that any part of our text of Al ha-Nissim dates to the Hasmonean period.

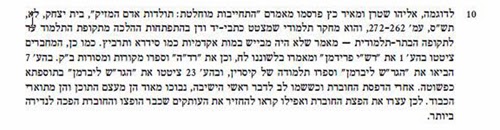

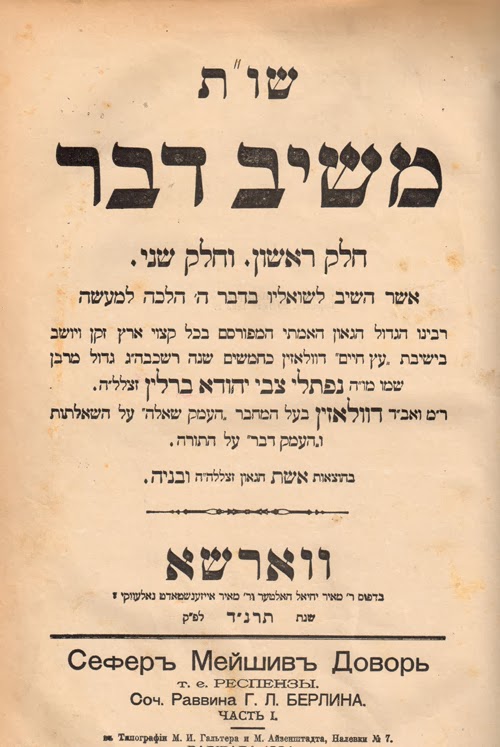

The concept of an insertion in the Amidah for Chanukkah is found already at Tosefta Berakhot 3:14. See also, in the Jerusalem Talmud, Berakhot 4:1 and 7:4, and in the Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 24a, and perhaps Shabbat 21b.[60]But exactly what was being recited in the Tannaitic and Amoraic periods remains unknown. The version recited today largely parallels what is found in the sources from Geonic Babylonia. The version recited in Palestine in the parallel period was much shorter. See Soferim 20:8 (20:6, ed. Higger).[61]The fact that the Babylonian and Palestinian versions differ so greatly suggests that the main text that we recite today for Al ha-Nissim is not Tannaitic in origin. On the other hand, both versions do include a line that begins biymei Matityah(u), so perhaps this line is a core line and could date as early as the late first century or the second century C.E.[62]

In any event, the prevalent version of Al ha-Nissim today, Matityahu … kohen gadol Chashmonai u-vanav, can easily be understood as utilizing Chashmonai as an additional name for Mattathias. But this may just be coincidence. It is possible that the author knew of both names, did not understand the difference between them, and merely placed them next to one another.[63]

On the other hand, we have seen the reading ve-Chashmonai in both Al ha-Nissim and Tractate Soferim. Perhaps this was the original reading, similar to the reading in many manuscripts of Megillah 11a. Perhaps all of these texts were originally composed with the assumption that Mattathias and Chashmonai were separate individuals. But there is also a strong possibility that these vavs arose later based on a failure to understand that the reference to Chashmonaiwas also a reference to Mattathias.

------

Postscript: Anyone who is not satisfied with my explanations for Chashmonai can adopt the explanation intuited by my friend David Gertler when he was a child. His teacher was talking to the class about Mattityahu-Chashmonai and his five sons, without providing any explanation of the name Chashmonai. David reasoned: it must be that he is called חשמניbecause he had five sons (i.e., חמשי metathesized into חשמי/חשמני)![64]

[1] I would like to thank Rabbi Avrohom Lieberman, Rabbi Ezra Frazer, and Sam Borodach for reviewing the draft.

I will spell the name Chashmonaithroughout, as is the modern convention, even though the vav has a shurukin the Kaufmann manuscript of the Mishnah and Chashmunai may be the original pronunciation

[2] The references to beit dino shel Chashmonai are at Sanhedrin 82a and Avodah Zarah 36b.

The balance of the references are at: Shabbat 21b, Menachot 28b and 64b, Kiddushin 70b, Sotah 49b, Yoma 16a, Rosh ha-Shanah 18b and 24b, Taanit 18b, Megillah 6a, Avodah Zarah 9a, 43a, and 52b, Bava Kamma 82b, and Bava Batra 3b. For passages in classical midrashic literature that include the name Chashmonai, see, e.g.,Bereshit Rabbah 99:2, Bereshit Rabbah 97 (ed. Theodor-Albeck, p. 1225), Tanchuma Vayechi 14, Tanchuma Vayechi, ed. Buber, p. 219, Tanchuma Shofetim 7, Pesikta de-Rav Kahana, p. 107 (ed. Mandelbaum), and Pesikta Rabbati 5a and 23a (ed. Ish Shalom). See also Midrash ha-Gadol to Genesis 49:28 (p. 866). The name is also found in the Targum to I Sam. 2:4 and Song of Songs 6:7.

The name is also found in sources such as Al ha-Nissim, the scholion to Megillat Taanit, Tractate Soferim, Seder Olam Zuta, and Midrash Tehillim. These will be discussed further below.

The name is also found in Megillat Antiochus. This work, originally composed in Aramaic, seems to refer to bnei Chashmunai and/or beit Chashmunai. See Menachem Tzvi Kadari, “Megillat Antiochus ha-Aramit,” Bar Ilan 1 (1963), p. 100 (verse 61 and notes) and p. 101 (verse 64 and notes). There is also perhaps a reference to the individual. See the added paragraph at p. 101 (bottom). This work is generally viewed as very unreliable. See, e.g.,EJ 14:1046-47. Most likely, it was composed in Babylonia in the Geonic period. See Aryeh Kasher, “Ha-Reka ha-Historiy le-Chiburah shel Megillat Antiochus,” in Bezalel Bar-Kochva, ed., Ha-Tekufah ha-Selukit be-Eretz Yisrael (1980), pp. 85-102, and Zeev Safrai, “The Scroll of Antiochus and the Scroll of Fasts,” in The Literature of the Sages, vol. 2, eds. Shmuel Safrai, Zeev Safrai, Joshua Schwartz, and Peter J. Tomson (2006). A Hebrew translation of Megillat Antiochuswas included in sources such as the Siddur Otzar ha-Tefillot and in the Birnbaum Siddur.

[3] Taanit 2:8 (66a) and Megillah 1:3 (70c). In the Piotrkow edition, the passages are at Taanit 2:12 and Megillah 1:4.

[4] This took place in 161 B.C.E. On this event, see I Macc. 7:26-49, II Macc. 15:1-36, and Josephus, Antiquities XII, 402-412.The story is also found at Taanit 18b, where the name of the victor is given more generally as malkhut beit Chashmonai.

[5]Mi-shel and beit are combined and written as one word in the Leiden manuscript. Also, there is a chirikunder the nun. See Yaakov Zusman’s 2001 edition of the Leiden manuscript, p. 717.

[6] The phrase echad mi-shel Chashmonai is awkward and unusual; it seems fairly obvious that a word such as beit is missing. Vered Noam, in her discussion of the passages in the Jerusalem Talmud about Judah defeating Nicanor, adopts the reading in Taanit and never even mentions the reading in Megillah. See her Megillat Taanit (2003), p. 300.

There are no manuscripts of the passage in Megillah other than the Leiden manuscript. There is another manuscript of the passage in Taanit. It is from the Genizah and probably dates earlier than the Leiden manuscript (copied in 1289). It reads echad mi-shel-beit Chashmonai. See Levi (Louis) Ginzberg, Seridei ha-Yerushalmi (1909), p. 180.

Mi-shel and Chashmonai are combined and written as one word in the Leiden manuscript of the passage in Megillah and there is no vocalization under the nun of Chashmonai here.

[7] I Maccabees was probably composed after the death of John Hyrcanus in 104 B.C.E., or at least when his reign was well-advanced. See I Macc. 16:23-24. II Maccabees is largely an abridgment of the work of someone named Jason of Cyrene. This Jason is otherwise unknown. Many scholars believe that he was a contemporary of Judah. Mattathias is not mentioned in II Macc. The main plot of the Chanukkah story (=the persecution of the Jews by Antiochus IV and the Jewish rededication of the Temple) took place over the years 167-164 B.C.E.

[8] M. Middot 1:6 (benei Chashmonai) and Seder Olam, chap. 30 (malkhut beit Chashmonai).

[9] I, 36. This view is also found in Seder Olam Zuta, chap. 8.

Earlier, at I, 19, he wrote that Antiochus Epiphanes was expelled by ’Ασαμωναίου παίδων (“the sons of” Chashmonai; see the Loeb edition, p. 13, note a. ). This perhaps implies an equation of Chashmonai and Mattathias, But παίδων probably means “descendants of” here.

[10] XII, 265. Jonathan Goldstein in his I Maccabees(Anchor Bible, 1976), p. 19, prefers a different translation of the Greek here. He claims that, in this passage, Josephus identifies Chashmonaiwith Simon. But Goldstein’s translation of this passage is not the one adopted by most scholars.

There are also passages in Antiquitiesthat could imply that Chashmonai is to be identified with Mattathias. See XX, 190, 238, and 249. But παίδων probably has the meaning of “descendants of ” (and not “sons of”) in these passages, and there is no such identification implied.

The ancient table of contents that prefaces book XII of Antiquities identifies Chashmonai as the father of Mattathias. See Antiquities, XII, pp. 706-07, Loeb edition. (This edition publishes these tables of contents at the end of each book.) But these tables of contents may not have been composed by Josephus but by his assistants. Alternatively, they may have been composed centuries later.

In his autobiographical work Life (paras. 2 and 4), Josephus mentions Chashmonai as his ancestor. But the statements are too vague to determine his identity. This work was composed a few years after Antiquities.

[11] Goldstein suggests (pp. 60-61) that Josephus did not have I Macc. in front of him when writing his Jewish War, even though Goldstein believes that Josephus had read it and was utilizing his recollection of it as a source. Another view is that Josephus drew his sketch of Hasmonean history in his Jewish War mainly from the gentile historian Nicolaus of Damascus.

Most likely, even when writing Antiquities, Josephus did not have II Macc. or the work of Jason of Cyrene. See, e.g., Daniel Schwartz, Sefer Makabimב (2008), pp. 30 and 58-59, Isaiah M. Gafni, “Josephus and I Maccabees,” in Josephus, the Bible, and history, eds. Louis H. Feldman and Gohei Hata (1989), p. 130, n. 39, and Menachem Stern, “Moto shel Chonyo ha-Shelishi,” Tziyyon 25 (1960), p. 11.

[12] I am not referring to the Palestinian version as Al ha-Nissim, since it lacks this phrase.

The text of Al ha-Nissim in the Seder R. Amram (ed. Goldschmidt, p. 97) is the same (except that it reads Matityah). See also R. Abraham Ha-Yarchi (12th cent.), Ha-Manhig (ed. Raphael), vol. 2, p. 528, which refers to Matityah kohen gadol ve-Chashmonai u-vanav, and seems to be quoting here from an earlier midrashic source. Finally, see Midrash Tehillim, chap. 30:6 which refers to Chashmonai u-vanav and then to beney Matityahu. The passages clearly imply that these are different groups.

[13] See the midrashim on Chanukkah first published by Adolf Jellinek in the mid-19th century, later republished by Judah David Eisenstein in his Otzar Midrashim (1915). Mattathias and Chashmonaiare clearly two separate individuals in the texts which Einsenstein calls Midrash Maaseh Chanukkah and Maaseh Chanukkah, Nusach‘ב. See also Rashi to Deut. 33:11 (referring to twelve sons of Chashmonai).

[14] As I write this, Lieberman-institute.com records four manuscripts that have Chashmonaiwith the initial vav like the Vilna edition, two manuscripts that have Chashmonaiwithout the initial vav (Goettingen 3, and Oxford Opp. Add. fol. 23), and one manuscript (Munich 95) that does not have the name at all. (Another manuscript does not have the name but it is too fragmentary.) There are three more manuscripts of Megillah 11a, aside from what is presently recorded on Lieberman-institute.com. See Yaakov Zusman, Otzar Kivei ha-Yad ha-Talmudiyyim(2012), vol. 3, p. 211. I have not checked these.

With regard to the passage in Soferim 20:8, there is at least one manuscript that readsחשמונאי (without the initial vav). See Michael Higger, ed., Massekhet Soferim(1937), p. 346, line 35 (text). (It seems that Higger printed the reading of ms.ב in the text here.)

[15] These midrashim are estimated to have been compiled in the 10th century. EJ 11:1511.

[16] The prevalent version is based on the Siddur Rav Saadiah Gaon (p. 255): Matityah ben Yochanan kohen gadol Chashmonai u-vanav.This version too can be read as reflecting the idea that Chashmonai was a separate person.

[17] Middot is a tractate that perhaps reached close to complete form earlier than most of the other tractates. See Abraham Goldberg, “The Mishna- A Study Book of Halakha,” in The Literature of the Sages, vol. 1, ed. Shmuel Safrai (1987).

[18] The above is the text in the Kaufmann Mishnah manuscript. Regarding the word beney, this is the reading in both the Kaufmann and Parma (De Rossi 138) manuscripts. Admittedly, other manuscripts of Mishnah Middot 1:6, such as the one included in the Munich manuscript of the Talmud, read ganzu beit Chashmonai.But the Kaufmann and Parma (De Rossi 138) manuscripts are generally viewed as the most reliable ones. Moreover, the beit reading does not fit the context. Since the references to Chashmonai in the Babylonian Talmud are often prefixed by the word beit and are never prefixed by the word beney, we can understand how an erroneous reading of beit could have crept into the Mishnah here.

The Mishnah in Middot is quoted at Yoma 16a and Avodah Zarah 52b. At Yoma 16a, Lieberman-institute.com presently records five manuscripts or early printed editions with beit, and none with bnei. At Avodah Zarah 52b, it records three with beitand one with beney. (The Vilna edition has beit in both places.)

Regarding the spelling חשמוניי in the Mishnah, most likely, this was the original spelling of the name. See the discussion below.

[19] See, e.g.,Bereshit Rabbah 99:2: חשמונאי בני ביד נופלת יון מלכות מי ביד, Bereshit Rabbah 97 (ed. Theodor-Albeck, p. 1225): לוישלמשבטוהיוחשמוניישבני, Pesikta Rabbati5a, Tanchuma Vayechi 14, Tanchuma Vayechi, ed. Buber, p. 219, Pesikta de-Rav Kahana, p. 107, and Midrash ha-Gadol to Genesis 49:28. See also the midrash published by Jacob Mann and Isaiah Sonne in The Bible as Read and Preached in the Old Synagogue, vol. 2 (1966), p. עב.

I also must mention the scholion to Megillat Taanit. (I am not talking about Megillat Taanit itself. There are no references to Chashmonai there.) As Vered Noam has shown in her critical edition of Megillat Taanit, the two most important manuscripts to the scholion are the Parma manuscript and the Oxford manuscript.

If we look at the Parma manuscript to the scholion to 25 Kislev, it uses the phrase nikhnesu beney Chashmonai le-har ha-bayit, implying that the author of this passage viewed Chashmonaias Mattathias.

On 14 Sivan, the Oxford manuscript of the scholion tells us that חשמונאיידוכשגברה, the city of קסרי was conquered. Probably, the author of this passage is referring to the acquisition of Caesarea by Alexander Yannai, and the author is using Chashmonai loosely. Probably the author meant beit Chashmonai or malkhut beit Chashmonai. (One of these may even have been the original text.)

On 15-16 Sivan, the Parma manuscript of the scholion tells us about the military victory of חשמונאיבני over Beit Shean. We know from Josephus (AntiquitiesXIII, 275-83 and Jewish War I, 64-66) that this was a victory that occurred in the time of John Hyrcanus and that his the sons were the leaders in the battle. But it would be a leap to deduce that the author of this passage believed that John was חשמונאי. Probably, the author was using חשמונאיבניloosely and meant beit Chashmonai or malkhut beit Chashmonai. Not surprisingly, the Oxford manuscript has beit Chashmonai here.

In the balance of the passages in the scholion, if we look only at the Parma and Oxford manuscripts, references to beit Chashmonai or malkhut beit Chashmonai are found at 23 Iyyar, 27 Iyyar, 24 Av, 3 Tishrei, 23 Marchesvan, 3 Kislev, 25 Kislev, and 13 Adar.

[20] This passage is quoted at Avodah Zarah 9a. In the Vilna edition, the passage reads malkhut Chashmonai. The three manuscripts presently recorded at Lieberman-Institute.com all include the beitpreceding חשמונאי. The other source recorded there is the Pesaro printed edition of 1515. This source reads חשמוניימלכות.

[21] One can also make this argument based on the passage in the first chapter of Megillah in the Jerusalem Talmud: משלחשמונייאחדויצא. This passage tells a story about Judah (without mentioning him by name). But the parallel passage in the second chapter of Taanit reads: חשמונייביתמשלאחדאליוויצא. As pointed out earlier, almost certainly this is the original reading. Moreover, if a passage intended to refer to a son of Chashmonai, the reading we would expect would be: חשמוניימבניאחד ויצא.

[22] Goldstein, p. 19, n. 34, writes that the Byzantine chronicler Georgius Syncellus (c. 800) wrote that Asamόnaios was Mattathias’ additional name. Surely, this was just a conjecture by the chronicler or whatever source was before him.

[23] The additional names for the sons were: Makkabaios (Μακκαβαîος), Gaddi (Γαδδι), Thassi (Θασσι), Auaran (Αυαραν) and Apphous (Απφους). These were the names for Judah, John, Simon, Eleazar and Jonathan, respectively. See I Macc. 2:2-4.

[24] See, e.g., Goldstein, pp. 18-19. Goldstein also writes (p. 19):

Our pattern of given name(s) plus surname did not exist among ancient Jews, who bore

only a given name. The names of Mattathias and his sons were extremely common in

Jewish priestly families. Where many persons in a society bear the same name, there

must be some way to distinguish one from another. Often the way is to add to the over-

common given name other names or epithets. These additional appellations may describe

the person or his feats or his ancestry or his place of origin; they may even be taunt-epithets.

The names Mattityah and Mattiyahu do occur in Tanakh, at I Ch. 9:31, 15:18, 15:21, 16:5, 25:3, 25:21, Ezra 10:43, and Nehemiah 8:4. But to say that that these names were common prior to the valorous deeds of Mattathias and his sons is still conjectural. (Admittedly, the names did become common thereafter.)

[25] See, e.g.,Daniel R. Schwartz, “The other in 1 and 2 Maccabees,” in Tolerance and Intolerance in Early Judaism and Christianity, eds. Graham N. Stanton and Guy G. Stroumsa (1998), p. 30, Gafni, pp. 119 and 131 n. 49, and Goldstein, pp. 7 and 12. See particularly I Macc. 5:62.

As mentioned earlier, I Maccabees was probably composed after the death of John Hyrcanus in 104 BCE, or at least when his reign was well-advanced. See I Macc. 16:23-24.

[26] According to I Macc. 2:1, Mattathias was from the priestly watch of Yehoyariv. Of course, even if he would have been from the watch of Yedayah, the rule of his descendants would have needed legitimization because they were priests and not from the tribe of Judah or the Davidic line.

[27] See, e.g., Goldstein, pp. 5-7 and I Macc. 2:26 and 2:54. Of course, the parallel to Pinchas is not perfect. As a result of his zealousness, Pinchas became a priest; he did not become the high priest.

[28]Goldstein, pp. 17-19. Josephus, writing after the destruction of the Temple and not attempting to legitimize the dynasty, would not have had this concern. (I am hesitant to agree with Goldstein on anything, as his editions of I and II Maccabees are filled with far-reaching speculations. Nevertheless, I am willing to take his suggestion seriously here.)

[29] As mentioned earlier, the identification by Josephus of Chashmonai as the great-grandfather of Mattathias is probably just speculation.

[30] It has been suggested that it was the name of an ancestor. See, e.g., H. St. J. Thackeray, ed., Josephus: Life(Loeb Classical Library, 1926), p. 3, who theorizes that the Hasmoneans were named after “an eponymous hero Hashmon.” Julius Wellhausen theorized that, at I Macc. 2:1, the original reading was “son of Hashmon,” and not “son of Simon.” See Emil Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ, revised and edited by Geza Vermes, Fergus Millar, and Matthew Black, vol. 1 (1973), p. 194, n. 14.

[31] See I Macc. 2:70, 9:19, and 13:25.

[32] See, e.g.,Isaac Baer, Avodat Yisrael (1868), p. 101, EJ 7:1455, and Chanukah (ArtScroll Mesorah Series, 1981), p. 68.

[33] See, e.g.,EJ 7:1455. Another less likely alternative is to link the name with Chushim of the tribe of Benjamin, mentioned at I Ch. 8:11.

[34] The probable implication of the second part of verse 32 is that the people of Kush will hasten to spread their hands in prayer, or hasten to bring gifts with their hands. See Daat Mikra to 68:32.

[35] This is raised as a possibility by many scholars. Some of the rabbinic commentaries that suggest this include R. Abraham Ibn Ezra and Radak. See their commentaries on Ps. 68:32. See also Radak, Sefer ha-Shoreshim,חשמן, and R. Yosef Caro, Beit Yosef, OH 682. The unknown author of Maoz Tzur also seems to adopt this approach (perhaps only because he was trying to rhyme with השמנים).

[36] Some scholars are willing to emend the text. See, for example, the suggested emendations at Encyclopedia Mikrait 3:317, entry חשמנים(such as משמנים = from the oil.) The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (1906) writes that there is “doubtless” a textual error here.

[37] So too, Origen (third century).

Some Rishonim interpret the termחשמנים here as rulers or people of importance. See, e.g.,the commentaries on Psalms 68:32 of Ibn Ezra (סגנים) and Radak. See also Radak, Sefer ha-Shoreshim, חשמן, and R. Yosef Caro, Beit Yosef, OH 682. What motivates this interpretation is the use of the term in connection with Mattathias. But we do not know the meaning of the term in connection with Mattathias.

[39] On the Egyptian wordḥsmn as bronze or natron, and reading one of these into this verse, see William F. Albright, “A Catalogue of Early Hebrew Lyric Poems,” Hebrew Union College Annual 23 (1950-51), pp. 33-34. Jeremy Black, “Amethysts,” Iraq 63 (2001), pp. 183-186, explains that ḥsmn also has the meaning amethyst in Egyptian. But he does not read this into Ps. 68:32. (He reads it into the Biblical חשמל.)

[40] See, e.g., Black, ibid., and Itamar Singer, “Purple-Dyers in Lazpa,” kubaba.univ-paris1.fr/recherche/antiquite/atlanta.pdf.

[41] Ludwig Koehler and Walter Baumgartner, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (1994), vol. 1, p. 362, interpret “bronze articles or red cloths.” Mitchell Dahood, Psalms II:51-100 (Anchor Bible, 1968) interprets “blue cloth.”

Based on the Akkadian, George Wolf suggests thatחשמנים refers to nobles and high officials because they wore purple clothing. See his Studies in the Hebrew Bible and Early Rabbinic Judaism (1994), p. 94

[42] For “oil,” see Encyclopedia Mikrait 3:317, entry חשמנים (one of the many possible interpretations mentioned there). For “horses and chariots,” see Daat Mikrato 68:32 (citing the scholar Arnold Ehrlich and the reference to the coming of horses and chariots at Is. 66:20).

[43] See Is. 59:10 באשמנים (in the ashmanim).

[44] Ernest Klein, A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the Hebrew Language for Readers of English (1987), p. 58, writes that it usually translated as “darkness.” Some Rishonim who adopt this interpretation are Menachem ben Saruk (quoted in Rashi) and Ibn Janach. Note also the parallel to Psalms 143:3. On the other hand, the parallel to בצהרים at Is. 59:10 suggests that the meaning of באשמנים is “in the light,” as argued by Solomon Mandelkern in his concordance Heikhal ha-Kodesh (1896), p. 158.

[45] See Midrash Tehillim (ed. Buber, p. 320): שחורים אנשים. This is the fourth interpretation suggested there. Buber puts the second, third, and fourth interpretations in parenthesis, as he believes they were not in the original text. The first interpretation is מנותדורונות. The second and third interpretations are farfetched plays on words.

Also, the original reading in the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan translation of חשמנים seems to be אוכמנא or אוכמנאי, meaning “dark people.” See David M. Stec, The Targum of Psalms (2004) p. 133. The standard printed editions have a different reading (based on an early printed edition) and imply that חשמנים was the name of a particular Egyptian tribe.

[46] See Mandelkern, p. 433, who cites this view even though he disagrees with it.

[47] A modern scholar who takes this approach is Menachem Tzvi Kadari. See his Millon ha-Ivrit ha-Mikrait (2006). This also seems to be the approach taken in the standard printed edition of the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, even though this does not seem to be the original reading. See also Rashi to Ps. 68:32, citing Menachem ben Saruk who claims that they are the residents of Chashmonah. See also Radak, Sefer ha-Shoreshim,חשמן(second suggestion) and Mandelkern, p. 433.

Gen. 10:14 mentions כסלחים as one of the sons of Mitzrayim. Interestingly, one of the three early texts of the Septuagint (codex Alexandrinus, fifth cent.) reads Χασμωνιειμ (=Chasmonieim) here. If this were the original reading, this would suggest that there were a people called Hashmanim (or something similar) in second century B.C.E. Egypt. But the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus codices (which are earlier than the Alexandrinus codex) do not have this reading; they have something closer to the Hebrew. Most likely, the reading in the Alexandrinus codex is just a later textual corruption. See John William Wevers, Notes on the Greek Text of Genesis (1993), p. 136.

[48] See similarly Deut. 33:21, Proverbs 1:27, Isaiah 41:5 and 41:25, and Job 3:25, 16:22, 30:14, and 37:22.

[49]The Kaufmann manuscript dates to the tenth or eleventh century. The Parma (De Rossi 138) manuscript dates to the eleventh century. The vocalization in both was inserted later. In the Kaufmann manuscript, there is a patach under the nun and a chirik under the first yod. Also, the vavis dotted with a shuruk. (The Parma manuscript does not have vocalization in tractate Middot; the manuscript is not vocalized throughout.).

The Leiden manuscript of the Jerusalem Talmud includes a chirik under the nun in the passage in Taanit (66a). See Zusman’s 2001 edition of the Leiden manuscript, p. 717. There is no vocalization under the nun in the passage in Megillah (70c).

[50] חשמונאי is the spelling in all but one of the manuscripts and early printed editions of Seder Olam. One manuscript spells the name חשמוני. See Chaim Joseph Milikowsky, Seder Olam: A Rabbinic Chronography (1981), p. 440.

Also, חשמוניי is the spelling in the text of Pesikta de-Rav Kahana that was published by Bernard Mandelbaum in his critical edition of this work (p. 107). (But see the notes for the variant readings.) Also, חשמוניי is the spelling in the text of the Theodor-Albeck edition of Bereshit Rabbah, at section 97 (p. 1225). (But see the notes for the variant readings.). See also ibid., p. 1274, note to line 6 (חשמניי).

Also, Lieberman-institute.com cites one manuscript of Menachot 64b with the spelling חשמוניי. This is also the spelling used by R. Eleazar Kallir (early seventh century). See his piyyutfor Chanukkah לצלעינכוןאיד (to be published by Ophir Münz-Manor).

[51] I would like to thank Prof. Richard Steiner for pointing this out to me.

[52] Jastrow, entry חשמונאי, cites the plural as appearing in some editions of Bava Kama 82b (but not in the Vilna edition.) Lieberman-institute.com presently records five manuscripts of Bava Kama 82b. All have the word in the singular here.

The EJ (7:1454) has an entry “Hasmonean Bet Din.” The entry has a Hebrew title as well: חשמונאיםשלדיןבית. The entry cites to Sanhedrin 82a and Avodah Zarah 36b, and refers to “the court of the Hasmoneans.” (In the new edition of the EJ, the same entry is republished.) Yet none of the manuscripts presently recorded at Lieberman-institute.com on these two passages have the plural. (Lieberman-institute.com presently records two manuscripts of Sanhedrin 82a and three manuscripts of Avodah Zarah 36b. According to Zusman, Otzar Kivei Ha-Yad Ha-Talmudiyyim, vol. 3, p. 233 and 235, there are three more manuscripts of Sanhedrin 82a extant. I have not checked these.)

Probably, the reason for the use of the plural in the EJ entry is that scholars began to use the plural for this mysterious bet din, despite the two references in Talmud being in the singular. See, e.g., Zacharias Frankel, Darkhei ha-Mishnah (1859), p. 43.

Other erroneous citations to a supposed word חשמונאים are found atChanukah (ArtScroll Mesorah Series), p. 68, n. 6.

[53] The earliest references to this plural that I am are aware of are at Midrash Tehillim 5:11 (ובניו חשמונאים), and 93:1 (חשמונאיםבני). But it is possible that חשמונאיםmay not be the original reading in either of these passages. The reference at 5:11 is obviously problematic. Also, the line may be a later addition to the work. See Midrash Tehillim, ed. Buber, p. 56, n. 66. (This work also refers to חשמונאיבית and ובניוחשמונאי. See 22:9, 30:6, and 36:6.) The next earliest use of this plural that I am aware of is at Bereshit Rabbati, section Vayechi, p. 253 (ed. Albeck): חשמונאיםבני. This work is generally viewed as an adaptation of an earlier (lost) work by R. Moshe ha-Darshan (11th cent.)

[54]חשמונים is found in the piyyutשמנהכלאעדיף by R. Eleazar Kallir (early seventh century) and in the works of several eighth century paytannimas well. Perhaps even earlier are the references in Seder Olam Zuta.See, e.g., the text of this work published by Adolf Neubauer in his Seder ha-Chakhamim ve-Korot ha-Yamim, vol. 2 (1895), pp. 71, 74 and 75. See also the Theodor-Albeck edition of Bereshit Rabbah, section 97, p. 1225, notes to line 2, recording a variant with the reading חשמונים. Also, Yosippon always refers to theחשמונים when referring to the group in the plural. (In the singular, his references are toחשמונאי and חשמוניי.) Also, Lieberman-institute.com cites one manuscript of Megillah 6a (Columbia X 893 T 141) with the reading חשמונים.

[55] See his Jewish War, II, 344, and V, 139, and AntiquitiesXV,403 (Loeb edition, p. 194, but see n. 1).

[56] It is interesting that a similar development occurred in connection with the name “Maccabee.” The name was originally an additional name of Judah only. Centuries later, all of the brothers came to be referred to by the early church fathers as “Maccabees.” See Goldstein, pp. 3-4.

[57] See, e.g., Allen Friedman, “The Amida’s Biblical and Historical Roots: Some New Perspectives,” Tradition 45:3 (2012), pp. 21-34, and the many references there. Friedman writes (pp. 26-27):

The first two points to be noted concerning the Amida’s history are that: (1) R. Gamliel

and his colleagues in late first-century CE Yavneh created the institution of the Amida,

its nineteen particular subjects, and the order of those subjects, though not their

fully-fixed text, and (2) this creation was a critical part of the Rabbinic response to the

great theological challenge posed by the Second Temple’s destruction and the ensuing

exile…

See also Berakhot 28b.

[58] Admittedly, this view disagrees with Megillah 17b which attributes the Shemoneh Esreh of eighteen blessings to an ancient group of 120 elders that included some prophets (probably an equivalent term for the Men of the Great Assembly.) But note that according to Megillah 18a, the eighteen blessings were initially instituted by the 120 elders, but were forgotten and later restored in the time of R. Gamliel and Yavneh. See also Berakhot 33a, which attributes the enactment of תפילות to the Men of the Great Assembly.

[59] See, e.g., the discussion by Joseph Tabory in “Prayers and Berakhot,” in The Literature of the Sages, vol. 2, pp. 295-96 and 315-316. Tabory points to disagreements recorded between the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai regarding the number of blessings in the Amidotfor Yom Tov and Rosh ha-Shanah when these fall on the Sabbath. See Tosefta Rosh ha-Shanah 2:16 and Tosefta Berakhot 3:13. Disagreements between the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai typically (but not exclusively) date to the last decades of the Temple period. See EJ 4:738. The reference to Choni ha-Katan in the story at Tosefta Rosh ha-Shanah also perhaps supports the antiquity of the disagreement. (This individual is not mentioned elsewhere in Tannaitic or Amoraic literature.)

[60] With regard to Birkat ha-Mazon, the practice of reciting Al ha-Nissim here seems to only have commenced in the Amoraic period. See Shabbat 24a.

[61] The first two words of the Palestinian version, פלאיךוכניסי, are also referred to in שמנהכלאעדיף, a Chanukkah piyyut by R. Eleazar Kallir (early seventh century).

[62] Early authorship of Al ha-Nissim is suggested by the fact that some of its language resembles language in I and II Macc. See particularly I Macc. 1:49, 3:17-20, 4:24, 4:43, 4:55, and II Macc. 1:17 and 10:7. See also perhaps I Macc. 4:59. The original Hebrew version of I Macc. was still in existence at the time of Jerome (4th century). See Goldstein, p. 16.

[63] It has already been pointed out that Josephus, having I Maccabees 2:1 in front of him (=Mattathias was the son of John who was the son of Simon), was faced with a similar problem. The solution of Josephus was to conjecture that Chashmonai was the father of Simon.

[64] I Macc. 2:2-4 states explicitly that Mattathias had five sons: John, Simon, Judah, Eleazar and Jonathan. Another brother, Ιωσηπον (=Joseph), is mentioned at II Macc. 8:22.But it has been suggested that the original reading here was Ιωαννης (=John), or that Joseph was only a half-brother, sharing only a mother.