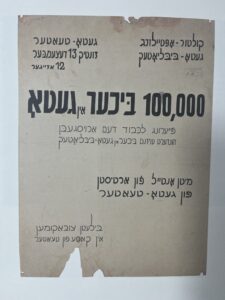

Abraham Rosenberg, R. Chaim Heller, R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach on Conversion, Abortion, Mercy Killings, and new pictures and videos of R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg

Marc B. Shapiro

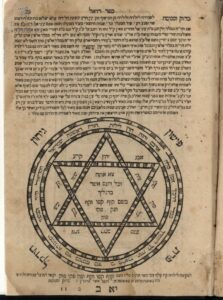

1. In my post here I discussed the enigmatic plagiarizer Abraham Rosenberg. As we saw, in 1923 and 1924 Rosenberg published articles on the Jerusalem Talmud in the Orthodox journal Jeschurun, and he later published Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi. In this last work, Rosenberg refers to R. Chaim Heller as his friend. I and so many others assumed that “Rosenberg” was a pseudonym, but Moshe Dembitzer, the expert on everything related to R. Heller, has pointed out to me that this appears not to be the case. Here is a letter Dembitzer found in the JDC archives from R. Heller to Cyrus Adler. As you can see, R. Heller mentions A. Rosenberg—the letter that is unclear must be an “A”—and one of his essays on the Jerusalem Talmud. He also mentions that Rosenberg “is considered only one of the ordinary students.”

![]()

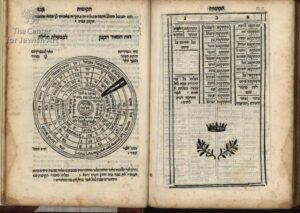

Dembitzer also found another connection between R. Heller and Rosenberg. Here is a note from R. Charles B. Chavel’s edition of Hizkuni’s commentary on the Torah, p. 525.

![]()

Here is Rosenberg’s Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi, p. 102, where he cites the same explanation that Chavel cited in the name of R. Heller (but Rosenberg takes credit for it himself).

![]()

Regarding the plagiarisms of Rosenberg, I must also thank Gershon Klapper who alerted me to other examples. He wrote to me:

Rosenberg’s first article (לחקר תלמוד הירושלמי) opens אין מן הצורך לשנות את הידוע כי תלמוד הבבלי שנחתם לא זזה ידם של חכמי ישראל ממנו, very similar to how R. Heller’s ע”ד מסורת הש”ס בירושלמי begins, אין מן הצורך לשנות את הידוע כי תלמוד הירושלמי הוא עדין כשדה שאין עובד בו. But the next part of his introduction to that article is taken, slightly rearranged, from Steinschneider’s ספרות ישראל vol. 2, p. 103 (it reappears at the beginning of ע”ד תקוני נוסחאות בירושלמי, which includes most of this article’s content), as is the line beginning פעולתם של הגאונים. He does paraphrase some other language from R. Heller in the introduction, but again it isn’t word-for-word.

His second article (פסוקי המקרא שבתלמוד) opens

כי חכמי התלמוד היו בקיאים בכל ספרי התנ”ך עד להפליא, – דבר זה ידוע לכל מי שלמד גמרא, ואפילו למי שהצליף בה סקירה שטחית. כמעט מכל דף ודף שבתלמוד נראה, כי פסוקי התנ”ך, ואפילו המקראות “האובדים והנדחים” שברשימות השמות בעזרא ובדברי הימים היו שגורים על פי התנאים והאמוראים בתכלית הדיוק. בעלי התוספות (ב”ב ד’ קי”ג בד”ה תרוייהו) לא חששו להחליט, שהאמוראים פעמים שלא היו בקיאים בפסוקים. אבל כבר הודו שם בעלי התוס’ עצמם שאין החלטה זו מוכרחת וכמו שכתב הרשב”ם שם. וגם הראיה שהביאו מדברי ר’ חייא בר אבא, שאינו יודע אם נאמר בי’ הדברות טוב או לא (ב”ק נה.) אינה מוכרחת שהרי ברור הדבר, כי דברי רחב”א, אינם אלא דברי בדיחותא, כדי לדחות את השואל.

Almost every word of this comes from an article of the same title by Yisrael Chaim Tawiow which appeared in HaShiloach 29 (July-Dec. 1913). The rest of the second article is taken from Baer Ratner, סדר עולם רבא pp. 103ff. and Samuel Rosenfeld, משפחת סופרים pp. 98, 100, 105, etc.

Klapper also called my attention to Rosenberg’s plagiarism of part of a paragraph in R. Heller’s article that appears in Le-David Zvi (David Zvi Hoffmann Jubilee Volume, Hebrew section). Compare p. 56 there with Rosenberg, Al Devar Tikunei Nushaot bi-Yerushalmi, p. 11. As Klapper notes, it is quite ironic that Rosenberg leaves out the following sentence from R. Heller that occurs in the middle of the passage he plagiarizes:

ויש שיועיל לנו הציון לברוח מן העבירה ולעשות מצוה לאמר דבר בשם אומרו

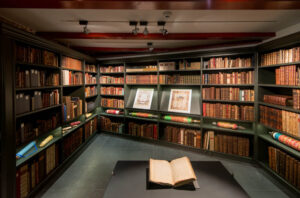

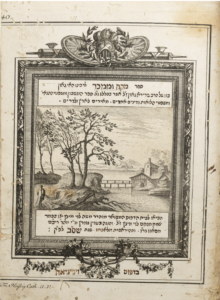

While on the topic of R. Chaim Heller, first let me share this wonderful picture from R. Ahron Soloveichik’s wedding in which one can see the Rav, R. Heller and R. Yaakov Kamenetsky. As far as I know, this picture has never appeared online. I thank Yoel Hirsch for providing me with the picture.

![]()

From R. Kamenetsky’s recently published Emet le-Yaakov al Nakh, vol. 1, p. 185 n. 2, we learn that in 1937 R. Kamenetsky visited Boston to discuss with R. Soloveitchik opening a yeshiva together.

In 1924 R. Heller published his study of the Samaritan version of the Torah, Ha-Nusah ha-Shomroni shel ha-Torah (Berlin, 1924). In 1972 Makor, which published so many valuable reprints of old seforim, decided to also reprint R. Heller’s Ha-Nusah ha-Shomroni. The problem was that R. Heller had an heir, and she was the only one with the legal right to reprint his books. This led to the following letters sent by Miriam Heller’s attorney (the letters are found in the Israel State Archives, 14924/3, available here [before the recent cyber attack on the archives], pp. 35ff.). From these letters, we learn that there were other unauthorized reprints of R. Heller’s works.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

One final point about R. Heller is the following: In 1912 he was appointed rav of the city of Lomza. Here is a report on his appointment from the newspaper Ha-Mitzpeh, March 29, 1912.

![]()

The writer is simply amazed that a Polish city, full of Hasidim, would hire as its rav a “Rabbi Dr.” Of course, R. Heller was a very unique “Rabbi Dr.”

2. Because I discussed conversion in the last post, I would like to call attention to R. Yoel Amital’s discovery of how R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach’s view on the matter has been presented.[1] The issue R. Amital focuses on is whether a conversion for someone who does not observe mitzvot takes effect. I am referring to one who tells the beit din at the time of conversion that he accepts the mitzvot, but we see later that this was not the case.

In his letter in R. Zvi Cohen’s Tevilat Kelim (1975), R. Auerbach is clear that ex post facto such a conversion is still valid.

The crucial words are:

בכגון דא נלענ”ד שכל המסייעים לגירות כזו, אף שבדיעבד הם גרים גמורים, אפי”ה המגיירים אותם עוברים בלאו של לפני עור וגו’

According to R. Auerbach, because be-diavad such converts are Jewish, to convert them is a violation of lifnei iver. As R. Auerbach explains, before conversion, these people could work on Shabbat and eat non-kosher, but now that they are Jewish they are forbidden to do so. By converting people who will be committing these and other sins, the beit din has violated the prohibition of lifnei iver.

As R. Amital shows, in subsequent printings of R. Cohen’s book, R. Auerbach’s letter is printed with a significant addition (here underlined):

בכגון דא נלענ”ד שכל המסייעים לגירות כזו, אף שהם טועים לחשוב שבדיעבד הם גרים גמורים, אפי”ה המגיירים אותם עוברים בלאו של לפני עור וגו’

And

בכגון דא נלענ”ד שכל המסייעים לגירות כזו, אף אם הם טועים לחשוב שבדיעבד הם גרים גמורים, אפי”ה המגיירים אותם עוברים בלאו של לפני עור וגו’

![]()

When this letter was printed in R. Auerbach’s Minhat Shlomo, vol. 1, no. 35:3, the wording was altered further:

בכגון דא נלענ”ד שכל המסייעים לגירות כזו, אף דהם טועים לחשוב שהם גרים גמורים, אפי”ה גם לשטתם המגיירים אותם עוברים בלאו של לפני עור וגו’

In Ha-Ma’yan 56 (Nisan 5776), p. 89, in response to R. Amital’s article, R. Aharon Goldberg, a grandson of R. Shlomo Zalman, published a picture of R. Auerbach’s original letter. The wording is identical to what appears in the first edition of R. Cohen’s book. So how to explain the later additions? R. Goldberg states that it is possible that the later changes were made with the consent of R. Auerbach. Although there is no evidence of this, I find it unlikely that R. Cohen would have altered R. Auerbach’s letter while R. Auerbach was still alive. A general rule of censorship and alteration of texts is that it is done after the author is no longer alive.

Leaving aside the updated version of the letter, there is still a problem that R. Amital confronts. According to R. Auerbach’s original letter, those who convert but do not become religious, their conversion is still valid. However, R. Auerbach also signed a public letter together with the Steipler, R. Shakh, and R. Elyashiv, which states that such a conversion has no validity. So which is it?

R. Mordechai Halpern has shown that R. Auerbach sometimes presented a “public” halakhah that was stricter than his true opinion, but which for some reason he did not wish to publicize.[2] R. Amital suggests that in this case we have a similar example where R. Auerbach publicly advocated a “strict” position regarding conversion that was not in line with his true opinion. (I put “strict” in quotes because while this position is strict in not regarding a conversion as valid, it is also “lenient” in that it tells someone who converted and did not intend to become religious that she can leave her husband without a get, does not need to fast on Yom Kippur, etc.)

R. Amital also claims, implausibly in my opinion, that the public letter R. Auerbach signed does not really stand in contradiction to the letter he sent to R. Cohen. How so? The public letter speaks of people who convert without accepting to observe mitzvot, while R. Auerbach in his letter to R. Cohen is referring to people who in front of the beit din do accept to observe mitzvot, but in their inner heart do not really have such an intention.

Contrary to R. Amital, this is clearly not what the public letter means. It is referring to people who converted in a beit din, but never intended to follow halakhah. It is simply impossible to read this public letter as referring to, in the words of R. Amital: גרים שלא קיבלו עליהם כלל בבית דין לקיים תורה ומצוות. There is no beit din in the world that does not require converts to accept Torah observance. The issue the letter was addressing is converts who, despite their verbal acceptance of mitzvot, do not follow through in practice. According to the letter, such a conversion is not valid. This is so obvious that one wonders how R. Amital could have ever offered his suggestion to explain the contradiction.

R. Halpern himself notes that he knows that R. Auerbach never backed away from his earlier position, as seen in his letter to R. Cohen, that someone who was converted by a proper beit din, but did not intend to observe mitzvot, ex post facto the conversion is still valid. Yet he states that R. Auerbach later concluded that this liberal approach should not be publicized.[3]

Even with the initial two “corrected” versions of R. Auerbach’s letter, R. Auerbach mentions that rabbis who convert people who have no intention of observing Torah violate the prohibition of putting a stumbling block before the blind. R. Auerbach states that until now the person converting violated Shabbat and ate non-kosher food and these were not sins. But now, after the conversion, he is violating the Torah. R. Auerbach concludes his letter as follows:

נמצא שכל המגיירים והמסייעים לכך הו”ל כגדול המחטיאו, ועוברים בלאו של ולפני עור לא תתן מכשול

The implication of this is that ex post facto the conversion is indeed valid, as otherwise there would be no sin committed by the convert and there would be no issue of putting a stumbling block before the blind. In the words of R. Yisrael Rozen:[4]

למדנו מדבריו שהגירות חלה, דאי לאו הכי אין כאן מכשול, שהרי נשאר בגיותו

In fact, we find many poskim who say that we should not convert people who do not intend on observing mitzvot, because then they will be punished for their sins. This shows that these poskim regard a conversion without intent to observe mitzvot as valid ex post facto. In a previous post here I cited a number of examples of this, and here is one more.

R. Raphael Shapiro, Torat Refael, vol. 3, no. 42, has a short responsum about whether to convert a woman who will not be observant. It was sent to R. Mordechai Klatchko of Volozhin, who would later come to the U.S. and serve as a rav in Boston.[5] R. Klatchko was clearly a fine talmid hakham, as can be seen from the two volumes of his Tekhelet Mordekhai. R. Klatchko wrote to R. Shapiro arguing that the woman should be converted even if she was not going to be observant so that her intended husband (or perhaps current husband) could fulfill the mitzvah of procreation (which he could not do if his children would not be halakhically Jewish). R. Shapiro disagrees and states that it is forbidden to convert her, as she will certainly not observe the niddah laws, and this will cause them both to violate a Torah prohibition.

![]()

What is important for our purposes is that both R. Klatchko and R. Shapiro assume that one who converts without intending to observe Jewish law is regarded as a valid convert. As long as the person goes through a halakhically proper conversion ceremony, that is what activates the conversion. It is hard for people today to understand how R. Shapiro never even raises the possibility that a conversion is invalid if the person converting intends to routinely violate fundamental Jewish laws by living an irreligious lifestyle. But as can be seen in so many different examples, a widespread view in prior generations—I don’t know if it was the majority view or not—was that as long as the conversion is carried out properly, what happens later, and what is in the convert’s heart at the time of the conversion ceremony, have no legal significance.[6]

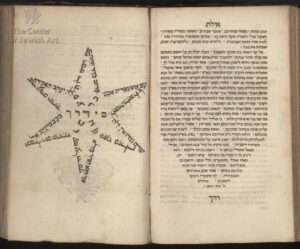

Here is one further example of this approach, Be-Mar’eh ha-Bazak, vol. 4, no. 96.[7]

![]()

As you can see, the approach of Kollel Eretz Hemdah is that there is no possibility of voiding a conversion carried out by a proper beit din, even if the people converting had no intention of observing mitzvot. At the beginning of the volume, it states that the responsa were reviewed by R. Zalman Nehemiah Goldberg, R. Nachum Rabinovitch, and R. Yisrael Rozen, all significant figures in their own right.

Finally, it is also worth noting that no less a figure than R. Isaac Jacob Weiss refused to void a conversion even though the woman who converted never observed mitzvot. See Minhat Yitzhak, vol. 1, nos. 121-123.

I have a good deal more to say about conversion, but in the interest of space, let me just call attention to a couple of interesting things I recently saw. The first is that R. Moses Sofer states that non-Jews are rewarded in this world if they convert to Judaism.[8] I do not know of anyone else who says that there is a divinely ordained reward for one who converts.

The second interesting discussion about conversion I recently saw is R. Aviad Sar Shalom Basilea, Emunat Hakhamim, ch. 24 (pp. 264-265 in the Jerusalem, 2016 edition). Adopting the type of anachronistic explanation that some commentators have been fond of, R. Basilea assumes that Mahlon converted Ruth and married her with huppah and kiddushin. But this creates a problem, because if Ruth was Jewish, why did Naomi push her away? R. Basilea offers a possible answer: Naomi held like the Rif and the Rambam that since Ruth’s immersion in the mikveh was not before three men, it was invalid even be-diavad. However, Mahlon held like the other poskim that be-diavad, tevilah by oneself if valid.

והנה נעמי היתה סוברת כרי”ף והרמב”ם שאפילו בדיעבד אינה גיורת ולכן השתדלה להרחיקה, ומחלון היה סבור כאותם הפוסקים הסוברים כי גיורת גמורה היתה ולכן נשאה

Does anyone, even from the most traditional communities, still offer explanations along these lines? Here is what R. Shimon Shkop wrote in a different context, and you can see that he was not a fan of this type of explanation.[9]

ודבר זה מביא לידי גיחוך, כעין הפלפולים אם פרעה היה סובר שעבודא דאורייתא

Some time ago I was looking at Abba Appelbaum’s book Rabbi Azariah Figo (Drohobycz, 1907), and he offers the following examples of anachronistic explanations (p. 54):[10]

R. Gershon Ashkenazi (1618-1693), one of the greatest halakhists of his day, also wrote a work of homiletics, Tiferet ha-Gershuni. In his derashah for parashat Mas’ei (p. 236 in the 2009 edition) he portrays the daughters of Zelophehad as arguing from halakhic logic.

In his derashah for parashat Va-Yera (p. 48), in discussing the descendants of Ishmael, R. Ashkenazi suggests that they held that the law of ketubah is rabbinic.

אם כן בני ישמעאל היו סבורים כתובה מדרבנן

Appelbaum also calls attention to R. Meir Schiff’s elaboration at the end of his commentary to Bava Kamma (found in the Vilna Shas). He portrays the incident of Esau selling his firstborn status from a halakhic angle. As such, Jacob’s thoughts were no different than those of a later halakhic scholar:

ונסתפק יעקב באומרו כיום מחמת שני דברים, שגריעותא דבכורה מחמת דבר שלא בא לעולם ומחמת אונאה . . . ויעקב נתיירא או למד הפשט כרש”י ולזה אמר ויאמר השבע לי כמ”ש בח”מ סי ר”ט ס”ד בהגה”ה

Another example, not mentioned by Applebaum, is R. Samuel Edels (Maharsha) in his aggadic commentary to Sanhedrin 57b. R. Edels wonders why Pharoah commanded the Hebrew midwives to kill the newborn Hebrew children, as it would have made much more sense to have Egyptian midwives do this. He explains that the children were to be killed before birth and for non-Jews this would be regarded as murder, which Pharoah wanted to avoid.[11] He thus turned to Hebrew midwives as for them it is not murder to kill an unborn child.

Quite apart from the far-fetched nature of the explanation, as well as its assumption that even before the giving of the Torah the Israelites were bound by Jewish law, not Noahide law, I don’t think any reader of the biblical story would find it reasonable that Pharoah was concerned about anyone violating the commandment against murder. However, the passage is also of interest in seeing how Maharsha regarded the prohibition against abortion.[12] He even portrays Pharoah as thinking that there is no prohibition for Jews to abort a fetus, including right before birth.

דודאי פרעה לא שאל מהם להרוג הזכרים בידים דבן נח מוזהר על שפיכות דמים ולכך לא אמר כן למילדות המצריות שהוזהרו על שפיכות דמים אפילו בעוברים אבל למילדות העבריות אמר שהותר לכם להרוג עובר במעי אמו וראיתם על האבנים קודם שיצא לאויר העולם אם בן הוא וגו’ וכיון שאי אפשר בהם לפטור משפיכות דמים רק בתחילת יציאת הולד קודם שיצא ראשו או רובו הוצרך לתת להם סימנין כמו שכתוב בפרק קמא דסוטה [יא ע”ב]

There has been a good deal of discussion as to how to understand the Maharsha’s words שהותר לכם. Some assume that he meant that Pharoah was in error in thinking that there is no prohibition for Jews to abort a fetus.[13] It is also possible to explain that the prohibition against abortion for Jews is only rabbinic,[14] so at that period of time there was no prohibition. R. Yaakov Farbstein states flatly:[15]

ומבואר במהרש”א דאין איסור לישראל בהריגת העוברים

This notion, that the Maharsha is saying that there is no prohibition for Jews to abort a fetus, is not in line with the overwhelming majority view beginning with the rishonim. However, in one Tosafot, Niddah 44a-b, s.v. ihu, it does state that abortion is permitted for Jews, and it does not mention that there needs to be a good reason for this or provide a timeline after which abortion is not allowed.

וא”ת אם תמצי לומר דמותר להורגו בבטן . . . וי”ל דמכל מקום משום פקוח נפש מחללין עליו את השבת אף ע”ג דמותר להרגו

Pretty much every halakhist who deals with abortion struggles with this Tosafot, as they have found it very hard to accept that any rishon could permit abortion without restrictions. One approach offered is that Tosafot is saying that there is no Torah prohibition, but there would still be a rabbinic prohibition.[16]

R. Moshe Feinstein, in his classic responsum on abortion, claims that there is a mistake in Tosafot, and instead of the two appearances of דמותר it should instead say דפטור ההורגו in both places.[17] This is in line with the phenomenon I have discussed on a few occasions, where R. Moshe is prepared to deny the authenticity of problematic texts. R. Eliezer Waldenberg offered a strong rejoinder to R. Moshe.[18]

והנה עם כל הכבוד, לא אדוני, לא זו הדרך, וחיים אנו עפ”ד גאוני הדורות, והמה טרחו כל אחד ואחד לפי דרכו לבאר ולהעמיד כוונת דברי התוס’ בנדה וליישבם, ואף אחד מהם לא עלה על דעתו הדרך הקלה והפשוטה ביותר לומר שיש ט”ס בדברי התוס’ ובמקום מותר צריך להיות אסור [צ”ל פטור]

While no other authorities agree with R. Moshe that the Tosafot contains a mistaken text, many regard the language of Tosafot as not exact.[19]

Returning to R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, I know of another example where he did not want a view of his to be widely shared. R. Amit Kula discusses R. Avigdor Nebenzahl’s argument that according to a variety of sources one who is suffering greatly is allowed to commit suicide. He further adds that it would be permitted to kill another in this circumstance (active euthanasia), for if you are allowed to kill yourself for a good purpose, you can do it to another as well. R. Nebenzahl adds that some of what he says comes from R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach. He also quotes R. Auerbach that one can take medicine to reduce pain even if it will shorten one’s life.[20]

This information, which appeared in the first edition of R. Nebenzahl’s Be-Yitzhak Yikare, is not found in subsequent editions. R. Kula tells us that in these editions R. Nebenzahl inserted a note that the section was removed at the instruction of an unnamed scholar, and R. Mordechai Halpern quotes R. Nebenzahl that this scholar was none other than R. Auerbach.[21]

I find this of interest because if there is one thing that everyone knows, it is that Judaism does not allow active euthanasia (mercy killing). As is usually the case, matters are more complicated as has recently been shown by R. Yitzchak Roness in an article in Ha-Ma’yan.[22] He notes that R. Moshe Sternbuch does not believe that there is any prohibition for non-Jews to engage in mercy killing, since it is carried out for a good purpose. R. Yitzhak Zilberstein also inclines towards this position, and R. Moshe Feinstein suggests this as well, writing:[23]

אפשר שבן נח אינו אסור ברציחה שהוא לטובת הנרצח ושאני בזה האיסור לישראל מהאיסור לבן נח

R. Moshe and others specifically have in mind a non-Jew engaging in mercy killing of a Jew. The proof brought is the famous story of the death of R. Hanina ben Teradyon (Avodah Zarah 18a) where R. Hanina permits the executioner to raise the flame and remove the wool from his heart, thus actively hastening his death. R. Shaul Yisraeli goes the furthest, and for someone suffering greatly, and near death, he thinks that active euthanasia is permitted even if performed by a Jew.

R. Roness then notes that there is a dispute if one suffering great pain is allowed to commit suicide. For the side that permits this, R. Zilberstein adds that if it is permitted for the suffering individual, it will also be permitted for another to assist (active euthanasia). R. Roness also cites R. Hershel Schachter who states that active euthanasia, with the agreement of the patient, is not to be regarded as murder. He even suggests that for one suffering greatly, active euthanasia should be permitted:[24]

ההורג את חברו ברשותו יש לומר דאין בו לאו דרציחה אלא רק לאו דאך את דמכם, דלא גרע הורג חברו ברשותו מההורג את עצמו . . . ולמנוע א”ע מלסבול ייסורים דינו כפקו”נ, וכמשמעות התוס’ הנ”ל. ואם באמת כ”ה גדר היתר זה, א”כ אף בחולה הסובל יסורים קשים ומתחנן לאחרים ליטול את נפשו, אם נאמר כנ”ל, דבכה”ג אין לומר דבטלה דעתו וכו’, ג”כ הי’ צ”ל מותר מטעם פקו”נ ועיין בזה

And finally, here is what R. Chaim Kanievsky responded when asked if a Jewish patient near death could allow a non-Jew to end his life. R. Chaim does not say this is murder. On the contrary, he is inclined to permit it.[25]

אם שוהה אדם בבית חולים דעכו”ם ויש לו יסורים רבים במחלתו האנושה, ורוצה הרופא לחסוך לו היסורים ולקרב מותו ושואל ממנו רשות, האם מותר לו להסכים לזאת. והשיב רבנו שליט”א “יתכן שיש ללמוד זה ממעשה דרחב”ת” . . . והיאך הסכים רחב”ת שהעכו”ם יקרב מותו, והשיב רבנו: “איפה שהחולה מרגיש שזה טובתו יתכן שמותר כמו שמותר להתפלל עליו שימות.”

My question is, how come the “liberal” views I have mentioned are not better known?

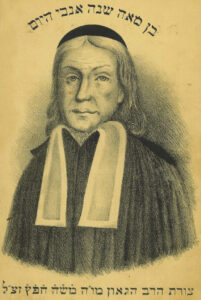

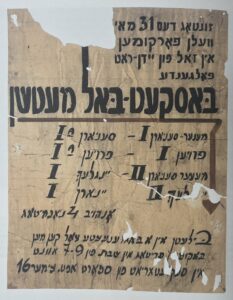

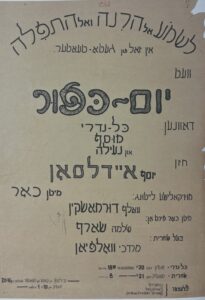

7. In my last post here I included the first-ever color pictures of R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg. These went around the world very quickly, and as is the nature of the internet, where the pictures came from was soon forgotten. In fact, within 24 hours someone who does not read the Seforim Blog sent them to me as a great new discovery. When I told him that I am the one who published the pictures he was at first incredulous, stating that he just got them from his cousin.

Here are two more pictures of R. Weinberg that he sent to his family. They are from before World War II when he was still in Germany. In the picture where he is lying the ground, I do not know who the couple next to R. Weinberg is.[26]

![]()

![]()

And for an extra treat, here are the only known videos of R. Weinberg, and one of them is in color. I thank Noam Cohn for putting this together, at my request, from his family’s collection. The first part has R. Weinberg with R. Arthur Ephraim Weil, the rav of Basel, and R. Leo Adler who succeeded Weil as rav of Basel in 1956. The second video, in which you can see R. Weinberg in color together with R. Samuel Brom, the rav of Lucerne, is from winter 1958-1959 at the Silberhorn kosher hotel in Grindelwald. The hotel had just inaugurated its new mikveh, and it was important to the family who owned the hotel that R. Weinberg give his approval to the mikveh.[27] At 1:12 and 3:20 you can also see the famed educator and student of R. Weinberg, Dr. Gabriel H. Cohn. Here is a picture from the event and you can see R. Brom and Dr. Cohn standing next to R. Weinberg.

![]()

Regarding R. Adler, before coming to Basel he studied ten years at the Mir Yeshiva, including in Shanghai. After the war he was in New York where he taught Torah at Yeshiva University.[28]

8. In my last post here I had the following quiz questions.

Please identify the following and email me your answers:

1. There are two se’ifim in the Shulhan Arukh that only contain two words.

2. There is one siman in the Shulhan Arukh whose number is the gematria of the subject of the siman.

The answer to no. 1 is Yoreh Deah 65:6: נוהג בכוי, and Even ha-Ezer 126:42: מותרת בויו

The answer to no. 2 is Orah Hayyim no. 586. This is the laws of shofar, and the gematria of shofar is 586. This was noted by R. Jacob Emden and I mentioned this in my article “‘Truth’ and Authorial Intent in the Study of Torah,” available here.

A number of people provided the correct answers for no. 1 and no. 2, but no one got both of my intended answers. However, Moshe Schwartz got no. 2 right with a different answer than I was thinking of (meaning he answered both questions correctly). He noted that Yoreh Deah 107 speaks about cooking eggs, and the gematria of ביצה is 107.[29] Also, shortly before this post was completed, Sol Reich provided another example: Yoreh Deah 334 is about הלכות נידוי וחרם and the gematria of נידוי וחרם is 334.

9. Information about my summer tours with Torah in Motion to Central Europe and Spain is available here.

* * * * * * *

[1] “Ha-Im Giyuram shel Gerim she-Einam Shomrim Mizvot Hal Be-Diavad? Berur Da’at ha-Gaon Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach ZTL,” Ha-Ma’yan 56 (Tishrei 5776), pp. 43-46.

[2] Halpern, Refuah, Metziut ve-Halakhah (Jerusalem, 2011), pp. 35ff.

[3] Amital, “Ha-Im Giyuram,” p. 45.

[4] Ve-Ohev Ger (Alon Shvut, 2010), p. 161 n. 1.

[5] See R. Hayyim Fischel Epstein, Teshuvah Shelemah, vol. 2, Even ha-Ezer, nos. 29-30, and R. Elijah Klatzkin, Hibbat ha-Kodesh, no. 11, where they respond to R. Klatchko’s question about a get written in Roxbury (a neighborhood in Boston), but the get only mentioned “Boston”. This is mentioned by Hayyim Karlinsky, Rabbi Hayyim Fischel Epstein (New York, 1963), pp. 26-27.

This R. Klatchko should not be confused with an earlier R. Mordechai Klatchko of Lida who also wrote a book titled Tekhelet Mordekhai. It is noteworthy that R. Klatchko of Lida wrote a lengthy haskamah for the Mishnah Berurah. Regarding R. Klatchko of Lida, see here.[6] For another example, see R. Dov Cohen, Va-Yelkhu Sheneihem Yahdav (Jerusalem, 2009), pp. 333-334. Here R. Cohen describes how, at the direction of R. Isser Yehudah Unterman, he converted a woman intent on marrying a completely irreligious Jew. This is the sort of conversion that today would not be allowed in Israel or in any of the batei din recognized by the Israeli Chief Rabbinate. See also R. Avraham Shapiro, Kuntres Aharon in his edition of R. Isaac Jacob Rabinowitz, Zekher Yitzhak (Jerusalem, 1990), p. 396, who suggests that according to Maimonides, when it comes to conversion and acceptance of mitzvot, כיון שקבל בפה אין דבריו שבלב דברים.

For a convert who is not observant, there is one halakhic consequence, at least according to many authorities: When they divorce the get should not say ben (or bat) Avraham avinu, but ploni ha-ger. See R. Shimon Yakobi, Bitul Giyur Ekev Hoser Kenut be-Kabbalat ha-Mitzvot (Jerusalem, 2009), pp. 103ff. (This is an official publication of the Israel rabbinical courts.) See also ibid., p. 105, for the shocking statistic that from 1996-2008, 97% of converts who divorced in the State of Israel were irreligious. There is no reason to doubt that the number of non-divorced converts who are irreligious is similar. If only 3% of converts in Israel are religious, then, as Yakobi rightly notes, it raises serious concerns about the conversion process.

[7] A similar responsum dealing with the same case appears in Be-Mar’eh ha-Bazak, vol 3, no. 89.

[8] Derashot Hatam Sofer, vol. 2, p. 301c. s.v. yeshalem.

[9] Hiddushei Rabbi Shimon ha-Kohen (Jerusalem, 2011), vol. 4, p. 324 (Kuntres Likutim, no. 5).

[10] I can’t say whether there is any plagiarism in this book, but another publication of Appelbaum was plagiarized from Abraham Berliner. See Nehemiah Leibowitz, “Al Devar ha-Takanah be-Venetzia,” Ha-Tzofeh le-Hokhmat Yisrael 13 (1929), p. 90.

Regarding anachronistic explanations, I think most would also include in this category R. Moses Sofer’s statement that Joseph wished to pray with a minyan rather than pray vatikin by himself. See Hatam Sofer al ha-Torah, vol. 1, p. 227.

[11] The same approach is independently suggested by R. Judah Rosanes, Parashat Derakhim, Derush 17, and R. Pinhas Horowitz, Panim Yafot, Ex. 1:15.

R. Ishmael holds that abortion is treated as murder for non-Jews (Sanhedrin57b) and Maimonides rules this way (Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Melakhim9:4). This halakhah has often been cited as proof that the crime of abortion is stricter for non-Jews than Jews, and that public policy should be in line with this. Yet in Sanhedrin 57b the Tanna Kamma disagrees with R. Ishmael and does not regard abortion as murder. In fact, according to the Tanna Kamma, abortion would seem to be permissible for non-Jews. R. Jeremy Wieder has raised the question, which I would like someone to offer a serious reply to, that while Maimonides and other authorities accept R. Ishmael as the binding decision, who says that non-Jews have to accept this? Why can’t non-Jews “poskin” like the Tanna Kamma? See here at minute 35:30.

R. Shneur Zalman Fradkin,Torat Hesed, Even ha-Ezer, no. 42:5 (in the note), suggests that Tosafot,Niddah 44a, that I discuss in the text, adopts the Tanna Kamma’s position, not the view of R. Ishmael. See Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 14, p. 184. The implications of this with regard to non-Jews are obviously significant.

See also R. Jacob Emden, Em la-Binah (Jerusalem, 2020), p. 197:

בילדכן את העבריות: לא גזר על שפיכות דמים אלא על העוברים

R. Emden seems to be saying that abortion is not regarded as murder for non-Jews. Perhaps relevant to this, it is worth noting that R. Meir Mazuz states that one should encourage a non-Jewish woman pregnant by a Jewish man to have an abortion. SeeMakor Ne’eman, vol. 3, no. 1509. See also R. Hanan Aflalo,Asher Hanan, vol. 8, no. 74. R. Joseph Babad, Minhat Hinnukh, 296:7, states that abortion is not murder for non-Jews, and therefore there is no law of rodef when it comes to a non-Jew seeking to kill a fetus. (Since later in this post I mention suicide, it is worth noting that R. Babad also states that non-Jews are not prohibited from committing suicide. See Minhat Hinnukh 34:8.)

Regarding abortion for Jews, R. Hershel Schachter has an interesting shiur here. His approach is, I think, the most lenient among contemporary poskim, as he states that for the health of the mother abortion is permitted up until the end of pregnancy, which is long after the time that the fetus is viable.

R. Schachter’s approach might be identical with the very lenient perspective of R. Abraham Isaac Bloch. See R. Mordechai Gifter,Milei de-Iggerot, vol. 7, p. 341:

בגדר האיסור דהריגת עוברין בישראל, שמעתי מאדמו”ר הגאב”ד ור”מ דטלז ז”ל הי”ד, שהוא מגדר בל תשחית, אשר לפי”ז כל שהוא לצורך רפואה או פגם משפחה, אין בזה גדר האיסור דהשחתה

[12] I would have thought that the Maharsha’s words could have halakhic significance, but R. Nahman Yehiel Michel Steinmetz states otherwise, noting אין לומדים הלכה מדברי הגדה. See Meshiv Nevonim, vol. 6, p. 250. See also R. Weinberg’s comments regarding the Maharsha in Seridei Esh, vol. 3, no. 126.

[13] See e.g., Siftei Maharsha: Shemot, pp. 16-17.

[14] For opinions that the prohibition against abortion is only rabbinic, see R. Yishai Yitzhak Shraga, Torat ha-Ubar (Jerusalem, 2017), pp. 72ff.

[15] Ohalei Yaakov: Shemot, p. 1.

[16] See R. Eliezer Waldenberg, Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 9, p. 231, vol. 14, p. 184.

[17] Iggerot Moshe, Hoshen Mishpat 2, p. 295. There are a couple of strange things in this responsum, which first appeared in the R. Yehezkel Abramsky Memorial Volume. For example, see p. 298 how R. Moshe describes R. Joseph Hayyim’s responsum in Rav Pealim. (The word שהחכם in the bottom line right column should be שהתחכם, as it appears in the R. Abramsky Memorial Volume.) Yet as R. Waldenberg points out, Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 14, p. 186, R. Moshe’s summary of Rav Pealim is inaccurate and he also does not show much regard for R. Joseph Hayyim, leading R. Waldenberg to write: והוא פלאי, ושרי ליה מריה בזה. See Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 14, p. 186. (R. Moshe actually ends his own responsum by saying ושרי ליה מריה בזה about R. Waldenberg.)

R. David M. Feldman wrote to R. Waldenberg that R. Moshe did not write the responsum on abortion, and that could explain what he saw as various problems in this responsum. SeeTzitz Eliezer, vol. 20, p. 140.

![]()

I find this approach completely untenable, although in conversation with me R. Feldman insisted on it. Some might suggest that others were involved in writing the responsum, and that explains the passage dealing with Rav Pealim. I find this impossible to accept, and would prefer to assume that at least with regard to the inaccurate Rav Pealim description, that R. Moshe did not have the text in front of him and was citing from memory from what had earlier been shown to him. As such, it is easy to imagine how he could have forgotten the details, as we have all had similar experiences. For more on this responsum, see my post here.

[18] Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 14, p. 183.

[19] See R. Zvi Ryzman, Ratz ke-Tzvi, vol. 2, p. 295.

[20] Tehumin 37 (2017), p. 124.

[21] Refuah, Metziut, ve-Halakhah, p. 28.

[22] “Ha-Im Muteret ‘Hamatat Hesed’ al Yedei Amirah le-Goy,” Ha-Ma’yan 62 (Tamuz 5782), pp. 54-64.

[23] Iggerot Moshe, Hoshen Mishpat 2, p. 313.

[24] Ginat Egoz, p. 74.

[25] R. Yosef Aryeh Lorintz, Mishnat Pikuah Nefesh, p. 26.

[26] The pictures in this post are now kept at Ganzach Kiddush Hashem in Bnei Brak.

[27] All the big rabbis stayed and ate at the Silberhorn hotel, and yet until 1975 it had no hashgachah. People knew the family that owned it to be absolutely reliable in matters of kashrut, and like the other kosher hotels in Switzerland, the kashrut was trusted without any hashgachah. In 1974 the Swiss rabbinate informed the various kosher hotels that they would need to acquire a hashgachah, thus ending the era of religious owners’ kashrut being trusted without any outside supervision. (Thanks to Dr. Joshua Sternbuch who passed on this information from the family who owned the Silberhorn hotel.)

Regarding R. Weil of Basel, R. Weinberg thought very highly of him. In one letter to R. Joseph Apfel (the date is unclear), R. Weinberg writes:

הרב ד”ר ווייל הוא אדם מצוין מאד בהשכלתו ובמדותי’. הוא מתלמידי בית מדרשנו מזמנו של הגרע”ה והגרד”ה ז”ל

In R. Weinberg’s letter to R. Apfel, March 16, 1952, he writes:

הרב דשם ד”ר ווייל (מתלמידי בית מדרשנו) הוא אדם תרבותי ובעל מדות

[28] Letter from Adler to Weinberg, Aug. 31, 1954.

[29] Already in elementary school I heard this word, as the name of the talmudic tractate, pronounced “beah”. I never understood why, and the rebbe probably wouldn’t have explained it if I asked. R. Solomon Luria states that we avoid the word beitzah as it also has a crude meaning (testicle), and therefore we use another word in its place. Yet it is reported that both the Vilna Gaon and the Hatam Sofer, as well as many others, did not accept this idea and used the word “beitzah”. See Otzrot ha-Sofer 18 (5768), pp. 82-83; R. Aharon Maged, Beit Aharon, vol. 11, pp. 254ff., R. Mordechai Tziyon, She’elot ha-Shoel, vol. 2, pp 350ff. (for many modern authorities).

Regarding the pious practice of eating eggs at seudah shelishit, see Kaf ha-Hayyim 289:12.

%20(1)_html_699a7594.jpg)

%20(1)_html_mf930eff.jpg)

%20(1)_html_a83250b.png)

%20(1)_html_6f0244b5.png)

%20(1)_html_635ceb31.png)

%20(1)_html_22fab565.png)

-Heschel%201c%20small.jpg)

-Heschel%201d%20small.jpg)

.jpg)