From Print to Pixel: Digital Editions of the Talmud Bavli

Ezra Brand

Ezra Brand is an independent researcher who resides in Tel Aviv. He has an MA from Revel Graduate School at Yeshiva University in Medieval Jewish History, and has studied in the Talmud Department of Bar-Ilan University. He has contributed a number of times previously to the Seforim Blog (tag), and a selection of his research can be found at his Substack blog. His most recent major work is a “Guide to Online Resources for Scholarly Jewish Study and Research”. He is currently working on an overview of names and naming in early Jewish literature. He can be reached at ezrabrand@gmail.com; any and all feedback is greatly appreciated.

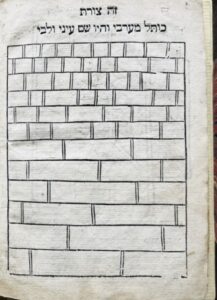

Intro – the tzurat hadaf[1]

It is a surprising fact that despite incredible advancements in technology, the layout of the Talmud has remained the same for centuries. The Bomberg edition from the 16th century, a groundbreaking achievement, still sets the standard. Yoel Finkelman writes in his recent, impressive overview of the layout of the printed Talmudic page:[2] “What is remarkable about the Gemara’s mise-en-page (the term for tzurat ha-daf in the academy) is not its invention, but its staying power as the normative way to produce texts of the Talmud.”[3] Finkelman then delves into the “history of the tzurat ha-daf of the Gemara.”

For an illustration of the lengths to which traditional publishers have gone to preserve the traditional tzurat hadaf, even in the 21st century, see Elli Fischer and Shai Secunda’s 2012 review article of the then-just-released “Artscroll Digital Library Schottenstein Talmud (English) App”, for the iPad:[4]

Since this elucidation is significantly longer than (and, in fact, already includes the actual text of) the Hebrew/Aramaic original, each Vilna page ends up being reproduced two to five times for every English page (a grey bar shows the reader which segment of the Vilna corresponds to the facing elucidation). This decision, both brilliant and perverse, added well over 10,000 pages, bringing the entire series to 73 volumes. The perversity of adding 10,000 apparently superfluous pages is obvious, but the brilliance of the decision was that it always kept the “original” page before the reader.

The digital daf

At the outset, Finkelman (in the above-mentioned article) highlights that the material manifestation of the written word can be broadly attributed to three factors: 1) The technological and material resources that are utilized to create and disseminate texts, 2) The economic and market forces that influence the demand for knowledge and education, and 3) The cultural perceptions of the role and function of language.[5] The ongoing decline in printing costs during the 20th and 21st centuries, coupled with the increasing accessibility of education, have led to significant advancements in all these factors.[6]

The advent of the internet has opened up entirely new avenues for publishing and designing the daf. Furthermore, for the very first time, readers have the opportunity to customize their reading experience, tailoring it to their unique preferences.

One popular author writes:[7]

“After more than a thousand years as the world’s most important form of written record, the book as we know it faces an unknown future. Just as paper superseded parchment, movable type put scribes out of a job, and the codex, or paged book, overtook the papyrus scroll, so computers and electronic books threaten the very existence of the physical book.”

However, one could plausibly say that the claim of the death of books has been greatly exaggerated. Physical books continue to be highly popular, and their sale has only continued to grow. And Orthodox Jews have yet an additional incentive to continue to buy physical books, as they can’t use ebooks on Shabbat and Chag. Regardless, there’s no question that we are in the middle of a decades-long revolution in how we have the ability to consume text, if one so chooses.

Despite the vast technological advancements that have revolutionized publishing, the digital daf is a peculiar return to pre-printing press methods in at least one regard: nowadays, the Talmud can be studied in isolation, without the surrounding commentaries. Most of the layouts that will be examined below diverge from the traditional tzurat hadaf that has been preserved for more than four centuries. In this way, they resemble the medieval Talmudic manuscripts, which include only the Talmud itself (sometimes accompanied by Rashi’s commentary).[8]

Let’s turn our attention to another aspect that Finkelman highlights: the groundbreaking nature of implementing a universal pagination system. Bomberg himself astutely utilized pagination and indexing as a key selling point.[9] Similarly, one of the numerous revolutionary features of digital editions such as Sefaria and Al-HaTalmud is the capacity to reference not only the daf and amud, but also the section number. (I’ll explain the specific details of this later in this piece.) One can cite using section number, and hyperlink directly to that section. Every amud has around 10-15 sections, so this narrowing down is considerable. Even without reference to a specific section, checking a reference is far easier in a digital edition: with a simple “control + f”, one can search for a word from the quote. Gone are the frustrating days of scanning a giant wall of text in an amud to find a quote.

What will be discussed in this review

My focus here will be on modern editions that are available open-access digitally, online.[10] Therefore, I won’t review modern print editions.[11] I will also not review digital editions that, in my opinion, are inferior in every way to the editions discussed here.[12] And I won’t discuss editions targeted towards beginner students.[13]

As one of the resources exclusively pertains to Kiddushin (Katz’s Mahberot Menahmiyot), my sample will be from Tractate Kiddushin, specifically Kid. 2b, which solely features the Gemara without the Mishnah. Images will only be of Gemara, Rashi, and Tosafot, meaning that, I will exclude the surrounding glosses (Mesoret HaShas, etc). I will not be discussing supplementary texts and commentaries, and hyperlinks to outside sources that each has.[14] I will be discussing different customization and viewing options.

Another caveat: This piece is focused on layout, and so it will not discuss the textual accuracy of the editions.[15]

An interesting element of modern editions is the typography; specifically the choices of font. However, this will not be discussed here.[16]

Outline

Intro – the tzurat hadaf 1

The digital daf 2

What will be discussed in this review 4

Outline 5

Tzurat hadaf AND customizable 6

Mercava 6

Shitufta 7

Static PDF 9

Mahberot Menahmiyot (=MM) 9

Gemara Sedura HaMeir 10

Talmud HaIgud – Society for the Interpretation of the Talmud (האיגוד לפרשנות התלמוד) 12

Digital, not customizable 14

Wikisource 14

Pirkei Talmud Me’utzavim – R’ Dan Be’eri 15

Talmud Or Meir 18

Dicta 19

Digital and customizable 20

Sefaria 20

Al-Hatorah 22

Speculation on the future 24

Concluding Thought 27

Tzurat hadaf AND customizable

At present, Mercava contains only Tractate Berachot. It includes a menu option that enables users to toggle punctuation and nikud. It is also worth noting that Mercava is presently in beta version, as stated explicitly by the page header. Many of the menu options are grayed out or non-functional, resulting in a suboptimal user experience. Often, it seems that two features cannot be employed simultaneously, without any discernible explanation.

Quite basic. It has section splits, which are the same as those of Sefaria and Al-Hatorah.[17] Like them, it enables linking to a specific section. However, it diverges from the section numbering in Sefaria and Al-Hatorah by commencing from 0 instead of 1, resulting in all section numbers in Shitufta being one less from those of Sefaria and Al-Hatorah.

Static PDF

Mahberot Menahmiyot (=MM)[18]

By Prof. Menachem Katz.

Image of Talmud text, from p. 3, line # 7:

MM is a static PDF. It divides every sentence into a separate line, as opposed to splitting into larger blocks of sections. The lines are numbered. It offers complete punctuation, without nikud.[19] MM displays citations for biblical verses, Mishnah, and Tosefta, as well as additional features discussed in the introduction.

Gemara Sedura HaMeir [20]

With punctuation, and split by line.

Talmud HaIgud – Society for the Interpretation of the Talmud (האיגוד לפרשנות התלמוד) [21]

The text is split into lines and numbered, similar to MM. Due to the nature of the work, the primary purpose of the Talmudic text in the Talmud HaIgud is not for its own sake, but to serve as a basis for subsequent commentary.

Digital, not customizable

Wikisource[22]

The crowd-sourced Wikisource is a sister-project of Wikipedia. It is replete with hyperlinks to primary sources, and to external secondary sources. Like MM, the text contains punctuation but not nikud. Instead of using numbered sections (like Sefaria and Al-Hatorah) or lines (like MM), the text is divided into unnumbered paragraphs. Moreover, these paragraphs are longer than those found in Sefaria and Al-Hatorah.

Pirkei Talmud Me’utzavim – R’ Dan Be’eri[23] [24]

Available as downloaded Word docs, from the Da’at website, for a few chapters. I consider this to be not customizable.[25] Has nikud, punctuation, and is split into numbered lines.

Has nikud, punctuation, and is split into numbered lines. While there are technically some customization options available, they are limited in scope.[26]

Dicta has a suite of powerful tools, which combined could make for an incredible studying experience. These include automated tools for nikud and for Biblical sources.[27] Unfortunately, at this time it appears that the only way to view a passage of Talmud is via search results. There, a link is offered to the page in Sefaria. There is a section called Library, with powerful tools for reading rabbinic works, but only 300 works are currently offered there.[28]

Here’s a screenshot, of what appears after searching the first words of Kidushin 2b (“אי נמי שדות בכסף יקנו”), opening the first result, and scrolling to 2b:

Digital and customizable

Sefaria[29]

Image of customization options:

Splits into numbered sections. In our example, there are 15 sections. The default Hebrew doesn’t split these into paragraphs, but there is an option to split into paragraphs. Many tractates have nikud, some have punctuation. Our example page doesn’t have punctuation, even though it shows that option. Sefaria gives the option to remove nikud. As mentioned, as with Shitufta and Al-Hatorah, one can hyperlink to a specific section.

Al-Hatorah[30]

The section numbers in circles on the right side of the page are hyperlinked, which is a convenient feature. In the example page we are looking at, there is no nikud, unlike Sefaria. However, there is a period after each section, which provides a slight advantage over Sefaria‘s lack of punctuation, as it helps to break up the passages when viewing with no section breaks.

While Al-Hatorah also includes hyperlinked sections, it does not explicitly label which section is which, unlike Sefaria. Therefore, finding a specific section requires trial and error. As with Shitufta and Sefaria, it is possible to hyperlink to a particular section in Al-Hatorah.

One notable difference is that Al-Hatorah does not expand acronyms, as Sefaria does. For instance, מ“ט is not expanded to מאי טעמא, and אב“א is not expanded to איבעית אימא.

Speculation on the future

Secunda and Fischer, in the faraway land of 2012 (cited at the beginning of this piece), envision a future Talmud app:

“First of all, it would be a virtually borderless intertextual web. Talmudic passages that shed light upon one another would be linked in intricate overlapping networks. Passages citing earlier texts—biblical verses, the Mishnah, other rabbinic texts, the apocrypha—would be hyperlinked to the collection in which the cited text originally appears. Passages would also link to later commentaries, super-commentaries, relevant excerpts from legal codes and responsa, manuscript variants, monographs, homiletic interpretations, and, indeed, translations and elucidations. Discussions of Akkadian medicine would call forth images of Babylonian tablets. People, places, historical events, concepts, practices, and all sorts of other realia mentioned in the text would link to relevant explanatory pages, pictures, recordings, and video clips. […] [T]wo new Jewish text websites, themercava.com and sefaria.org, offer promising platforms for crowd-sourced translation, commentary, and discussion of the Bavli and other Jewish texts. […]”[31]

While some aspects of this idealistic vision have been realized, many others have not, at least not yet. Moreover, it remains unclear whether a more crowdsourced and social-media-oriented approach, (suggested in an un-cited part of Secunda and Fischer’s article), would even be desirable. In retrospect, the year 2012 was marked by somewhat utopian thinking, with Wikipedia and Facebook having recently achieved great success in spreading knowledge and connecting people worldwide. It seemed only natural to aspire to something similar in the realm of literature. However, today, with greater awareness of the unpredictable dynamics of such systems (such as misinformation), it is far from clear that such a goal is attainable or even desirable.

In my view, Sefaria, Al-Hatorah, and Dicta are the most promising candidates for realizing the immersive and highly hyperlinked experience envisioned by Fischer and Secunda. Once this is achieved, the resulting research tools are likely to be extremely powerful as well. However, the idea of leveraging comparative sources, as described by the authors, still seems quite far off, particularly with the current set of available tools.

Regarding the social and chavruta aspect discussed by Fischer and Secunda, a new possibility has emerged that was not even envisioned a year ago: an artificial intelligence-powered chavruta. I recently experimented with ChatGPT by providing it with the first paragraph of Kidushin 2b.[32]

As usual, ChatGPT demonstrated impressive coherence and confidence. However, it provided laughably incorrect interpretations. In fact, in some cases, it provided interpretations that were the exact opposite of the correct one.

I conducted a comparable test by inputting a paragraph of Ramban’s commentary on that sugya, requesting an explanation from ChatGPT. To my surprise, ChatGPT provided a reasonably good rephrasing in English. Although some of it was correct and some of it was incorrect, even the incorrect part was not entirely off. However, ChatGPT still requires further yeshiva study before being able to serve as a teacher.[33]

Given the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence and large language models, it appears highly likely that AI will continue to improve its ability to interpret the Talmud, along with all other sources, including digitized manuscripts. It may not be long before we turn to AI to obtain the ultimate p’shat in the Talmud.[34] Furthermore, there is a possibility that AI could eventually bring comparative sources to bear, as previously mentioned.

To update the speculative future envisioned by Fischer and Secunda, my ideal Talmud study experience would be an app with a GTP plug-in acting as a virtual chavruta/Rebbe, to interpret text and answer questions. In fact, something like this is already being tested by Khan Academy.[35]

With current tools, it will even be possible to create a virtual shiur.[36] In the future, it could even be live and interactive, happening in real time.

Another interesting idea that is ripe to be explored is visualization of the Talmudic text. This was put to the test by Yael Jaffe, in a 2015 Columbia dissertation.[37] Jaffe writes in her abstract (bolding is mine):

“This study investigates the effect of access to a visual outline of the text structure of a Talmudic passage on comprehension of that passage. A system for defining the text structure of Talmudic passages was designed by merging and simplifying earlier text structure systems described for Talmudic passages, following principles taken from research on text structure. Comprehension of two passages were compared for students who did traditional reading of a Talmudic passage (the passages had punctuation added, and a list of difficult words and their meanings was appended) (the control condition), and students who read the passage with these same materials as well as with an outline of the text structure of that passage (the experimental condition) […]

The results provide evidence that awareness of the text structure of a Talmudic passage helps readers when the passage is concrete and somewhat well organized. ”[38]

It is interesting to note that Jaffe’s control group had punctuation added. There is, in fact, no good reason why the punctuation should not be added to all the standard Vilna-Romm editions. This is something that I did as a matter of course in my gemaras in my yeshiva days, and I presume that I was not the only one.[39]

Concluding Thought

Will there ever be a single Talmud application to rule them all, similar to how the Bomberg layout remained the standard for 500 years, and continues to do so? Such a scenario is improbable and perhaps even unwanted in today’s rapidly changing and complex digital landscape. It would suggest a lack of progress. We may have to wait for the arrival of the Messiah or, at the very least, the AI singularity to provide the ultimate Talmud super-app.

[1] This piece was written as part of preparation for the workshop “Editions of Classical Jewish Literature in the Digital Era”, to be held at University of Haifa, June 18-20, 2023, at which I’ll be presenting. I want to express my gratitude to Menachem Katz for his efforts in organizing that workshop, and for inviting me to speak there. I’d also like to thank Eliezer Brodt for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this piece. I would also like to thank my father, my brother, and S. Licht for reviewing, making suggestions, and helping clarify in conversation some of the ideas discussed.

[2] Finkelman, ”From Bomberg to the Beit Midrash: A Cultural and Material History of Talmudic Page Layout”, Tradition (Winter 2023), Issue 55.1, p. 14. I’d like to thank Eliezer Brodt for bringing this article to my attention.

[3] Immediately before, he writes (my bolding): “[T]he famous and ubiquitous tzurat ha-daf (page layout) of the Gemara was never exclusively by Talmudists for Talmudists. It was a common practice for producing non-Jewish European glossed texts in manuscript and later print from the high middle-ages though the sixteenth century. Some copyists and later printers of the Gemara—whether those printers were Jews or not—adopted it from contemporary Christian textual production.” This point is also made by Michele Chesner, in her interview on the Seforim Chatter podcast: “With Michelle Chesner discussing old books, Seforim, and more” (April 29, 2020).

[4] “Brave New Bavli: Talmud in the Age of the iPad”, Jewish Review of Books (Fall 2012). Archived here.

[5] Finkelman, pp. 16-17.

[6] Relatedly, I have heard the theory a few times from Prof. Meir Bar-Ilan that the writing down of the Talmud may have occurred due to the spread of the Chinese invention of printing to the West in the early medieval period. For some work on when the Mishnah and Talmud were first written, with previous scholarship cited, see: Yaakov Elman, “Orality and the Redaction of the Babylonian Talmud”, Oral Tradition, 14/1 (1999): 52-99 ; Shamma Friedman, “The Transmission of the Talmud and the Computer Age”, in Sharon Liberman Mintz and Gabriel M. Goldstein, eds., Printing the Talmud: From Bomberg to Schottenstein (2005), pp. 143-154 (esp. pp. 146-148) ;

יעקב זוסמן, “‘תורה שבעל פה‘ פשוטה כמשמעה: כוחו של קוצו של יו“ד“, מחקרי תלמוד ג, א (תשס“ה), עמ‘ 209-384 (נדפס שוב כספר ב– 2019) ; נחמן דנציג, “מתלמוד על פה לתלמוד בכתב: על דרך מסירת התלמוד הבבלי ולימודו בימי הביניים“, בר–אילן ל–לא (תשס“ו), עמ‘ 49-112.

[7] Keith Houston, The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time (2016), introduction (available via Amazon Kindle sample). He adds in a footnote: “It is worth introducing “codex” as a technical term: it means specifically a paged book, as opposed to a papyrus scroll, clay tablet, or any of the myriad other forms the book has taken over the millennia.”

[8] Recently pointed out by Ari Zivotofsky in a Seforim Blog post (“The Longest Masechta is …”, March 31, 2023): “[I]t is worth noting that ambiguity regarding sizes of masechtot only arose when commentaries began to be put on the same page as the text of the gemara. In other words, until the era of the printing press there was no ambiguity as to which masechta was the longest.” See also Finkelman, pp. 18-19 ; Friedman, “Printing”, p. 148. The early Soncino editions also only contained the Gemara and Rashi, see Finkelman, pp. 22-24. And see the recent statement of Yehuda Galinsky (bolding is mine): “The end of the thirteenth century witnessed a discernable growth in the composition of glossed works in Ashkenaz. It was from this time onwards that authors penned influential talmudic and halakhic works from France and Germany with the intention that they be accompanied by a supplementary gloss, which was to be copied alongside the text […] Instead, we find stand-alone commentaries that were copied separately from the text it was interpreting. In contrast to the well-known layout of the printed Talmud page, the writings of Rashi and Tosafot were written and usually copied as stand-alone commentaries and not as actual glosses to be copied on the same page.” (Judah Galinsky, “The Original Layout of the Semak”, Diné Israel, Volume 37 (2023), pp. 1*-26*, pp. 1-2.) A commenter to Zivotofsky’s blogpost pointed out that there is a print edition that contains only the Talmud (with supplementary indexes). It was printed 25 years ago. Here’s bibliographic info according to the National Library of Israel catalog entry:

תלמוד בבלי: כולל כל המשנה והמסכתות הקטנות : נערכו, סודרו והודפסו מחדש בכרך אחד, עם חלוקה לפסקאות, איזכורים מהמקרא, מלווים בשבעה מפתחות בסגנון אנציקלופדי, כולל מפתח ערכים אלפבתי, בעריכת צבי ה‘ פרייזלר … הרב שמואל הבלין … הרב חנוך הבלין (1998).

As an aside, Finkelman states (p. 18) that “The earliest [Talmudic manuscripts] are Geniza fragments from the ninth century”. However, see Friedman, pp. 147-148, that the earliest Talmudic manuscript is a scroll that can be dated to the 7th century.

[9] Finkelman, pp. 25-28. See also the interesting point by Finkelman, p. 41 (based on Jordan Penkower), that Bomberg was also the one to establish the standard method of citation for Tanach in the Jewish world: “In his first Mikraot Gedolot, Bomberg made a significant addition by adding chapter numbers and (in the second edition) verse numbers, features with little Jewish precedent which were based on thirteenth-century Catholic developments.”

[10] See my recent “Guide to Online Resources for Scholarly Jewish Study and Research – 2022”, where I discuss many of the resources discussed in this piece with more breadth. There I also discuss many of the resources excluded from this review for the reasons enumerated further. Bar-Ilan Responsa Project’s Talmud is online, but is not open-access. Bar-Ilan Responsa Project’s Talmud is linked from Yeshiva.org.il’s Talmud pages, top right of page. (See on Yeshiva.org.il in a later footnote.) That version of Bar-Ilan Responsa Project’s Talmud has punctuation, but no nikud, and is not split into sections/paragraphs, and is inferior in every way than the editions discussed here.

For the same reason (not open-access), I have not reviewed any editions on Otzar HaHochma, or other digital libraries which require a subscription.

[11] Such as Vagshal, Oz VeHadar, Shas Vilna HeChadash, Gemara Sedura. See image here of layout of Gemara Sedura. (See Shimon Steinmetz’s interesting piece here on self-censorship in the Vagshal edition: “Vagshal’s revision of the history of the Vilna Talmud, or, One of the most egregious examples of censorship I have ever seen”.) The best completely static tzurat hadaf edition that I could find available online as open-access is the Moznaim edition, available at Daf-yomi and HebrewBooks. It is a PDF, simply re-typeset. There are also printed editions with punctuation, such as Steinsaltz-Koren; Oz VeHadar; and Tuvia’s. See these news articles from 2016 on Oz VeHadar’s (ongoing?) Talmud edition with nikud and punctuation: here and here. And see the National Library of Israel (=NLI) catalog entry here. See also the NLI catalog entry on Yosef Amar’s 1980 Talmud edition (17 vols.) with nikud based on Yemenite pronunciation, here. And see NLI catalog entries of Koren’s (ongoing?) Talmud edition with nikud and punctuation: Sanhedrin (2014) ; Bava Metzia (2015) ; Sukkah (2016) ; Bava Batra (2017) ; Kidushin (2018).

[12] So I won’t discuss the following: Kodesh.snunit ; Mechon Mamre ; Daf-yomi.com > “Text”. Daf-yomi.com’s “Chavruta commentary” and “tzurat hadaf” are indeed worthwhile. See previous note on Daf-yomi.com’s Moznaim tzurat hadaf edition. The Friedberg Project website Hachi Garsinan technically has a few digital editions of Talmud on their website, but they are all for the purpose of presenting the manuscript variants. So I won’t be reviewing that, since this piece is focused on layout and UX/UI, and in that regard, the edition is sub-par. (Again, this is not necessarily a critique, as this isn’t the point of those editions.) As I say further, in this piece I will not discuss the editions’ textual accuracy. For this reason, I also won’t discuss The Academy of the Hebrew Language’s Ma’agarim edition. Tashma.jewishoffice.co.il’s Talmud shows promise, but for now seems to be inferior in every way than the editions discussed here. The website Yeshiva.org.il (פרשני – ויקישיבה) has the Chavruta commentary of the Talmud. However, as mentioned, the original PDFs of Chavruta commentary are available on the Daf-yomi.com website, so in my opinion it’s clearly best to use that. There’s no advantage to the text version (except for the ability to copy-paste). Yeshiva.org.il’s Chavruta is fully editable, wiki-style. But I see that as a negative, as you don’t know what you’ll be getting.

[13] Such as Gemara Brura and The People’s Talmud. See more at R’ Josh Waxman’s blogpost, “Some excellent Talmud projects out there” (March 5, 2020).

[14] For example, Sefaria and Al-Hatorah have the Steinsaltz translation and commentary, and Wikisource has extensive links to other resources.

[15] Many of the textual elements of the Vilna-Romm edition have been superseded by better editions (though many are still incomplete). Some examples:

תלמוד: דקדוקי סופרים (השלם); הכי גרסינן

רש“י: מהדורות פרופ‘ אהרן אהרנד

תוספות ; תוספות ישנים; רבינו חננאל : מהדורות רב קוק

עין משפט: עינים למשפט של ר‘ יצחק אריאלי (כל שבעה כרכים זמינים בהיברובוקס, לדוגמא, כאן)

מסורת הש“ס: דקדוקי סופרים השלם; תלמוד האיגוד

[16] For now, see Yakov Mayer in his recent ground-breaking book on the first edition of Talmud Yerushalmi (which was also printed by Bomberg’s press), who cites previous studies on typefaces used by Bomberg: Yakov Z. Mayer, Editio Princeps: The 1523 Venice Edition of the Palestinian Talmud and the Beginning of Hebrew Printing (2022, Hebrew).

See also the recent book by Simon Garfield, Just My Type: A Book About Fonts (2011 ) for a fascinating, well-written, popular overview of typesetting and fonts. On medieval handwriting styles of Hebrew, see the monumental 3-volume series, under Malachi Beit-Aryeh’s editorship (each area is a different volume):

מפעל הפליאוגראפיה העברית, אסופות כתבים עבריים מימי–הביניים (1987-2017)

On second temple era styles, see the various works by Ada Yardeni, especially:

עדה ירדני‘ ספר הכתב העברי: תולדות, יסודות, סגנונות, עיצוב (1991).

[17] It is unclear to me who first made these section splits. It’s a question I’d be quite interested in knowing the answer to.

[18] Links to all of parts of MM:

Compare Katz’s similar work on Yerushalmi (which also includes textual variant apparatus, and short commentary, unlike his work on Bavli), available at his Academia.edu site: “פסחן ומצתן של נשים Women on Passover and Matzah”.

[19] I personally prefer this style (punctuation, without nikud). See my discussion later.

[20] Tractate Sukka, p. 2 (ב). Not to be confused with Gemara Sedura (no HaMeir). Currently available online: Tractate Sukka (2013, here) and Tractate Avoda Zara (2015, here). See more on the project here.

[21] From the latest volume available online:

נתנאל בעדני, סנהדרין פרק חמישי (תשע“ב), עמ‘ 4.

See more on the project here.

[22] See more on the project here.

[23] See also some of R’ Be’eri’s other editions, available on Da’at website, here and here. On R’ Be’eri, see the Hebrew Wikipedia entry on him: דן בארי – ויקיפדיה

[24] Screenshot of downloaded Word document.

[25] To explain: Even though everything in the Word doc can be customized, this isn’t built into the website. Any of the editions in this “Digital” section can be pasted into a Word document and customized.

[26] Notably, the text itself is actually an image, which makes copying it impossible.

[27] Dicta was started by Prof. Moshe Koppel of Bar-Ilan University. He has contributed to Seforim Blog.

[28] As of 15-Apr-23.

[29] See more on the project here.

[30] See more on the project here.

[31] Compare also, at length, Friedman, “Printing”, pp. 150-154 ; Shai Secunda, “Resources for the Critical Study of Rabbinic Literature in the Twenty-First Century” in Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum (CRINT) 16, Christine Hayes (ed.), (2022), pp. 621-632.

[32] On 15-Apr-23, at https://chat.openai.com/.

[33] I should point out that I did not have access to GPT-4, which is the latest version of GPT. So I could not test whether GPT-4 is more capable at interpreting Talmud. For a discussion of some sources of the Yeshivish dialect of English possibly used as datasets for training ChatGPT-4, see my “From the Shtetl to the Chatbot: Some contemporary sources of Yeshivish content, in light of ChatGPT-4”.

[34] For some preliminary algorithmic research on the Talmud, see, for example, Satlow M., Sperling M. (2017). “Naming Rabbis: A Digital List”; Satlow M., Sperling M. (2020), “The Rabbinic Citation Network”; Satlow M., Sperling M. (2020). “The Rabbinic citation network”, AJS Review ; Zhitomirsky-Geffet M., Prebor G. (2019), “SageBook: toward a cross-generational social network for the Jewish sages’ prosopography”, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 34(3), pp. 676–695 ; “A graph database of scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud”, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, Volume 36, Issue Supplement_2, October 2021, Pages ii277–ii289, https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqab015, Published: 22 February 2021. See also Shira Shmidman, “Self-Evident Questions and Their Role in Talmudic Dialectic”, AJS Review (2023), p. 128: “Recently, I analyzed talmudic questions (that open with the phrase baʿei or beʿah minei) and discovered that by charting the questions by the generation in which they were asked, one can identify chronological trends of question asking in the Babylonian Talmud.”

[35] See Sal Khan, “Harnessing GPT-4 so that all students benefit. A nonprofit approach for equal access”, Khan Academy Blog (March 14, 2023). See especially this description: “Khanmigo [=the AI tool] engages students in back-and-forth conversation peppered with questions. It’s like a virtual Socrates, guiding students through their educational journey. Like any great tutor, Khanmigo encourages productive struggle in a supportive and engaging way.” For fun, I asked ChatGTP for a clever name for an AI chavruta/Rebbe. It gave me ten options. One of them is a great one (ChavrutAI), while three of them were hilarious ( AIvrumi; AIsh Torah; RoboRabbi). RoboRabbi could provide many of the intellectual aspects of being a rabbi: psak, eitza, questions in learning, and divrei torah.

[36] With tools like ChatGPT (content), ElevenAI (voice), D-ID (video), one can create any style of shiur. See my “Heimish High-Tech: Video in Yeshivish dialect using Generative artificial intelligence”. For training sources for the Yeshivish dialect, see my article: “From the Shtetl to the Chatbot: Some contemporary sources of Yeshivish content, in light of ChatGPT-4”.

[37] Jaffe, The Relevance of Text Structure Strategy Instruction for Talmud Study: The Effects of Reading a Talmudic Passage with a Road-Map of its Text Structure (2015). See especially ibid. Appendix E (pp. 103-104).

[38] On visualizations, see also this article, and the bibliography cited there:

יעקב אמיד, “עיצוב ייצוגים גרפיים של דיון תלמודי: תחום דעת מתחדש בהכשרת מורים להוראת תלמוד“

See also the lengthy intro of Menachem Katz to his Mahberot Menahmiyot (discussed earlier), with relevant bibliography. One good existing resource for outlines and charts for Talmud is Daf Yomi Advancement Forum – Kollel Iyun HaDaf. See Josh Waxman, “Some excellent Talmud projects out there” (cited earlier), #2. A fascinating related project is that of R’ Dr. Michael Avraham on mapping out the logic of the Talmudic sugya, using the tools and notation of modern logic. See his massive series Studies in Talmudic Logic, currently at 15 volumes. Note the surprising claim made in the abstract of vol. 14 of the series (Andrew Schumann, ed., Philosophy and History of Talmudic Logic, bolding is mine): “The Talmud introduces a specific logical hermeneutics, completely different from the Ancient Greek logic. This hermeneutics first appeared within the Babylonian legal tradition established by the Sumerians and Akkadians to interpret the first legal codes in the world and to deduce trial decisions from the codes by logical inference rules. The purpose of this book is (i) to examine the Talmudic hermeneutics from the point of view of its meaning for contemporary philosophy and logic as well as (ii) to evaluate the genesis of Talmudic hermeneutics which began with the Sumerian/Akkadian legal tradition. The logical hermeneutics of the Talmud is a part of the Oral Torah that was well expressed by the Tannaim, the first Judaic commentators of the Bible, for inferring Judaic laws from the Holy Book.”

[39] My suggestion for breaking the tzurat hadaf into sections: the pilcrow (¶). On the pilcrow, see the entertaining popular book, Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks (2013) by Keith Houston, chapter 1. (Available from Amazon for free as a Kindle sample.)

It should be pointed out that trop is an early medieval Hebrew form of punctuating the Biblical text. A few alternatives of punctuating the Torah arose in Geonic times.

On early nikud of Mishnah and Talmud, especially nikud bavli (we use nikud tavrani), see Yeivin:

ישראל ייבין, מסורת הלשון העברית המשתקפת בניקוד הבבלי (תשמ“ה), פרקים ב–ו.

I will point out the following: Tuvia’s edition adds nikud. But once one is past the beginner stage, nikud does little to enhance the reading experience, and in fact many readers find it a distraction. Modern Hebrew rarely uses nikud. Exceptions are for literature geared towards children and beginners (as noted), as well as instances where decoding is especially difficult, such as poetry, transliterated foreign words, and ambiguous words. In contrast, punctuation is a huge boost to faster comprehension, as Jaffe notes. Modern Hebrew texts use standard punctuation, like all modern languages.

.jpg)

.jpg)

There are two notable works by R. Emden, his Siddur, (

There are two notable works by R. Emden, his Siddur, (

.jpg)