Chaim Zelig Slonimsky and the Diskin family

by Zerachya Licht

Two years ago, the Seforim Blog published an article, written by Zecharya Licht, about the maskil, Chaim Zelig Slonimsky, and the Chanuka controversy he'd ignited.

Last year, the Seforim Blog published published Part I of another article, also written by Zecharya Licht, which again focused on the above-mentioned maskil. This second article highlighted Slonimsky's relationship with the Diskin Family.

Part II of the article, which had already been published, zeroed in on Slonimsky's relationship with R' Binyomin Diskin of Horodna, the patriarch of the illustrious and rabbinical Diskin family. In this article, Licht reproduced hitherto unknown letter written by R' Yehoshua Leib's son, Binyomin Diskin to the maskil, Shmuel Yosef Finn. In that letter, Binyomin Diskin mentions the relationship between Slonimsky and Diskin’s grandfather R' Binyomin of Horodna.

Presented here is Part II of the monograph which focuses on R' Yehoshua Leib's connection with Slonimsky. In the appendixes, R' Yehoshua Leib's positive relationship to the Haskalah is discussed. The enlightenment of the wider Diskin family, and R' Abbele Paslover's attitude towards the books published by the maskilim, are also discussed here.

Perakim א' through ד' appear in Part I.

פרק ה: מציאות הנפש - השכלתו הכללית של מהרי"ל דיסקין.

נספח א: יחסו של מהרי"ל דיסקין להשכלה כללית בעודו משמש ברבנות באירופה.

נספח ב: יחסם להשכלה כללית של שאר בניו וחתנו של רבי בנימין דיסקין.

נספח ג: הסכמות מרבי אבלי לספרי משכילים.

פרק ה

מציאות הנפש - השכלתו של מהרי"ל דיסקין

בחנוכה שנת תרי"ב הוציא חז"ס לאור את ספרו 'מציאות הנפש' ששמו המלא הוא 'מציאות הנפש וקיומה חוץ לגוף – מבואר על פי ראיות נכוחות הלקוחות מן בחינות הטבע'. בדבריו "אל הקורא" כתב המחבר, שספרו מיועד לאלה "אשר ספר אלה [ספרים ההולכים על דרך העיון והמחקר] ואלה [ספרי מוסר והיראה הנמצאים אתנו למרבה] בלתי נכון לפניהם לפשט עקמומיות שבלב, והמה האנשים אשר ..."

נראים הדברים שספרו 'מציאות הנפש' מצא חן בעיני הרבנים, ויעיד עליו העובדה שספר זה צוטט ע"י הגאון רבי מרדכי גימפל יפה האב"ד ראזיאני[1] בספרו 'תכלת מרדכי' על הרמב"ן (בראשית א, יד). אמנם מה שמעניין ביותר הוא שיתכן מאד שגם הגאון רבי יהושע ליב דיסקין זצ"ל עשה שימוש בספר זה. שהרי בכתביו של מהרי"ל דיסקין נמצא כתוב:

העיקר, ידוע אנחנו מאמינין בהשארות הנפש, ואולם חה"ע[2] מודים בזה, לפי שלא נמצא בעולם שום נברא שנעדר מן העולם, כי אם לבוש צורה אחרת, וכן הנשרף נשאר אפר והעודף בעשן נשאר נחלק למים ואויר, ונפש זה שהכרנוה בחיים איפה היא? אם לא שישנה בפני עצמה וכו'.[3]

רעיון זה שיש להוכיח השארת הנפש מ'חוק שימור החומר' שגילו המדענים בני המאה ה-18 מופיע בפרק ראשון מהספר 'מציאות הנפש'. מטרת הפרק היא, בלשונו של חז"ס, ש"יבאר שאין הפסד וכליון, השבתה ואבדון בעולם ואם הנפש נמצאה במציאות אי אפשר עוד שיאבד נצחה אחרי מות הגוף". סביר להניח שמהרי"ל דיסקין ראה דבר זה בשם חכמי האומות העולם בספרו של חז"ס ומשם רשם רשימתו הנ"ל.

כבר פרסם הפרופסור מלך שפירא בספרים בלוג שהגאון רבי יהושע ליב ציין לספר 'הכורם' מהמשכיל נפתלי הירץ הומברג[4]. הומברג היה מחבריו של משה מנדלסון ואף כתב את ה'ביאור' על חומשים במדבר ודברים. מה שמפתיע ביותר הוא מה שגילה הרב אליעזר בראדט במאמרו על קופרניקוס[5] שבסדר יומו של מהרי"ל דיסקין שנתפרסם מתוך כתב ידו מצאנו שמהרי"ל דיסקין קיבל על עצמו "לעיין בספרים פלפול אגדה דרוש מחקר פלוסופי' השכלה...". לאור תגליות אלו לא רחוק הוא לומר כהשערתי שמהרי"ל עיין גם בספר של עמיתו חז"ס. טרם שנמשיך לשרטט עוד פרטים אודות חז"ס ופעילותיו הספרותית, אעיר על איזה פרטים שבתוך סדר היום הנ"ל של מהרי"ל.

יש להעיר שהמהדיר בספר זכרון יהוסף, סילף כוונת מהרי"ל דיסקין, בכוונה או שלא בכוונה. בהערה כ"ב 'מפרש' המהדיר הנ"ל, שקבלתו של מהרי"ל דיסקין ללמוד 'ספרי פלוסופיה' היינו ספרים כמו מורה נבוכים להרמב"ם וכדומה, דבר זה עדיין בכלל הגיוני. אבל בהערה כ"ג 'מפרש' שקבלת מהרי"ל דיסקין ללמוד 'ספרי השכלה', היינו ספרי קבלה והיא מלשון 'השכל וידוע אותי', זה הפירוש כבר מביא הקורא לידי גיחוך[6]. הכל יודעים מה זה 'השכלה' ואין כאן מקום לפרשה בתרי אנפין. ועוד, אפילו אם יתעקש בזה המתעקש, הלא סדר הדברים מורה שמהרי"ל קבע הזמן לפני הליכתו לשינה לדברים יותר קלים הדורשים שיעור פחות של ריכוז המוח: פלפול, אגדה, דרוש, מחקר, פילוסופיה, השכלה. ואם נפרש כולם כפשוטם, הרי לפנינו סדר של לימוד דברים קלים ולא כל כך רציניים כמו שאר לימודיו במשך היום, אבל אם נפרש שהכוונה לקבלה אז אין כאן סדר של מהכבד אל הקל. וכבר שקלו וטרו בזה באוצר החכמה פורום ואין צורך לכפול את הדברים. עוד פרט חשוב שראוי להעיר עליו הוא, שמהרי"ל קבע לימודו ב"פרשה חומש ורש"י ואבן עזרא". וידוע שפירוש האבן עזרא אהוב ביותר על בעלי המחקר והשכלה. וגם על פרט זה לא דלגו עיניו של המהדיר הנ"ל, וכדי להגן על מהרי"ל דיסקין וגינוניו האנטי-משכיליים מצא לנכון להוסיף בהערה ד' שהגרנ"צ ווייס רשם כמה פעמים על דברי האב"ע "אין הדין כן – מהרי"ל דיסקין זצ"ל". הרי במקום שאנו יכולים ללמוד ממהריל"ד שיש לקבוע לימודינו בפירוש האבן עזרא, בא המהדיר להעיר לנו שדברי האבן עזרא הם נגד הדין!

עובדה נוספת מעניינת מאד מופיעה בהקדמה ל'אלון בכות' [הספד על מהרי"ל] שנכתבה על ידי תלמידו הרב יעקב אורנשטיין[7] ובה הוא מונה את אותן החכמות שהשתלם בהן אביו של מהרי"ל, הגאון רבי בנימין, כחכמות שהצטיין בהן גם מהרי"ל:

החכמות שיש בהם צורך לתוה"ק בכולם היה לו עשר ידות, בהנדסה, באלגיברה, בתכונות שמים וגלגלי המזלות, בכל אלה למד ולימד הפליא עצה הגדיל תושיה – בכל אלה לו דומיה תהילה[8] ע"כ דבריי מעטים.[9]

הרי לנו עדות מפי תלמיד מהרי"ל שניתן ללמוד ממנה, שבאותן חכמות שהצטיין בהן רבי בנימין דיסקין, ואחריו חז"ס, גם מהרי"ל הצטיין בהן, והן אלגברה ותכונות השמים.

¨¨¨

נחזור לספר 'מציאות הנפש'. בהשקפה הראשונה נראה שתוכן הספר הוא חיזוק אמונה בהשארת הנפש. ואכן לפי ר' יעקב ליפשיץ, התבטא בזה השתייכותו של חז"ס למשכילי דור הישן שכיבדו את המסורה:

החכם מר חז"ס נחשב בימים ההם ממשכילי הדור הישן כמו שכנה הוא את עצמו באיזה מאמרו "תלמיד מבית המדרש הישן", ובספריו ובמאמריו מימי נעוריו התראה כעין מגן ומחסה למסורת אבות. שלתכלית זו נחבר את ספרו 'יסוד העיבור' ומחברתו 'מציאות הנפש' להוכיח אמיתת השארת הנפש.[10]

ברם, הוסיף ר' יעקב ליפשיץ:

המבקרים המומחים הכירו גם במחברותיו אלה שצפונה בם ארס של חפשיות עד שאפילו הסופר המפורסם 'ליליענבלום'[11] יאמר במחברתו הידועה 'חטאת נעורים' שמאז שקרא את המחברת 'מציאות הנפש' התעוררה בלבבו הספק של מציאות הנפש'.[12]

עם כל זה מסיק ליפשיץ:

ביחס למשכילי דורו שקפצו בעזות להיות לרוכבים ומנהיגים על ישראל בכח הרשות והטיחו דברים בספרותם כלפי מסורת אבות, נחשב חז"ס לבעל נימוס, ורבים נהגו בו כבוד ויקר.

יש שטענו שערבוביה זו של חיזוק אמונה יחד עם קרירותה, לא הייתה מקרית. אלא שבכוונה חיבר חז"ס ספרים שבאופן רשמי באים לחזק את הדת, אבל במקום לחזקה, הטמין בו חז"ס ארס נגד הדת. אברהם אריה עקביא[13] מעיר, שבכל מאמריו וספריו נזהר חז"ס שלא לגלות שמץ של כפירה באלקים ולא לפגוע ברגשי אנשי הדת; ולא עוד, אלא דווקא בהגיעו במחקריו המדעיים לנקודות העלולות לשמש יסוד או ראייה לכפירה, דווקא שם הוא מוצא לנכון לדבר בשבח האמונה ולהאדיר את גדולת אלקים הכל יכול, אבל לא תמיד נראים כיוצאים מלב אמת.[14] עקביא ממשיך להביא דוגמא לכך – ובלשונו "היא הדוגמה החריפה ביותר"– מהספר הקטן בעל השם הארוך 'מציאת הנפש וקיומה חוץ לגוף מבואר על פי ראיות נכוחות הלקוחות מן בחינות הטבע'. תמצית דבריו של עקביא היא, שבמקום להוכיח את השארת הנפש, מסיק חז"ס כי כל הראיות שהביא לשם כך לא היו אלא ראיות על דרך ההיקש ואילו מופת מוחלט המוכיח מצד עצמו את מציאות הנפש וקיומה בהיפרד מן הגוף אי אפשר למצוא בשום פנים, אלא שטבע האדם הוא, שאין הוא יכול להאמין בכיליון הנפש... אחת היא האמונה באושר הנצחי המנחמת את האדם מכל יגון החיים, אשרי אדם עוז לו בה! הרי בא ללמד הוכחות להשארת הנפש ונמצא למד שאין לאמונה זו מופת.

יתר דברי חז"ס ומעשיו יופיעו בעזהי"ת בעתיד

נספח א

יחסו של מהרי"ל דיסקין להשכלה כללית בעודו משמש ברבנות באירופה

מעניין לעניין, ברצוני להזכיר כמה רמזים שמצאתי פה ושם המורים על השקפתו החיובית של מהרי"ל דיסקין לשאר חכמות בכל אותן השנים ששימש ברבנות בחו"ל. בזמן שבתו בירושלים היה ידוע למקנא קנאת ה' נגד אלו שהלכו לרעות בשדי נכרים. לכן, הדבר מפתיע ביותר שלא כן היו נראים פני הדברים בעודו יושבת בארץ טמאה, חוצה לארץ.

1. תקופת קאוונא:

כשנתקבל מהרי"ל לשמש כרב אב"ד בעיר הגדולה קאוונא (1861) נתפרסם בהמגיד מודעה אודות התמנותו. מתוך סגנון הדברים משמע שהרב יהושע ליב רכש לו לכה"פ איזו ידיעות בעניני העולם:

קאוונא בחודש האביב. כתפארת ערי ישראל הבנויות לתלפיות בימי עולם, ככה אשוה אותך קאוונא בגודל וביקר. עתה לא לשוא תוכלי להתפאר ולאמר לערים הנכבדות והגדולות ממך: לא נופלת אנכי מכן; הן רבניך ומנהליך מימי עולם בישראל גדול שם. המה כללו יפיך ביתר שאת מני-עד. המה שמוך נאדרי בקדש על כל הערים אשר סביבותיך. לא אדבר משנות קדם כי אין ספורות למו, אך מהדור החי הזה את אשר חזו עינינו אספרה. בך הרב הגאון חסיד ועניו כו' מוהר"ר ישראל סלאנטער שליט"א זרע זרע אמת פרי חיים על תלמי לבב בניך בדבריו החוצבים להבת אש דת-יה בלב וקרב איש. בקרבך הורה דעת וצדק הרב הגאון פאר זמננו מ' יצחק אביגדור הי"ו, ומה מאד נעלית קריה נאמנה עתה, עת אשר עיניך ראות את מוריך אשר עתה מחדש נגלה נגלה בהדר גאוני שעריך, לרעות בצדק עדתך בעקבות מנהליך הקודמים הוא הרב הגאון חכם הכולל כו' מו"ה יהושע יהודא ליב הי"ו אשר ישב בעיר לאמזא כסא אביו הגאון הצדיק וישר מ' בנימין זלה"ה. לכן עורי קאוונא והתעוררי לקראת איש אשר אלה לו לאשר עדת ישרון על פי דרכי התורה והחכמה. ולטעת מטעי יראת האל לבבבם לשים עין על כל דרכיהם ומעללותיהם. ולכן קריה עליזה ראוי ונכון להיות אלוף לראשך איש כמוהו. יען מה? יען כי חכמיך וסופריך מגפן התורה והמדע גפנם, גביריך וקצינך ענבימו ענבי צדקה וחסד... דוב בער ווארשאווסקי[15]

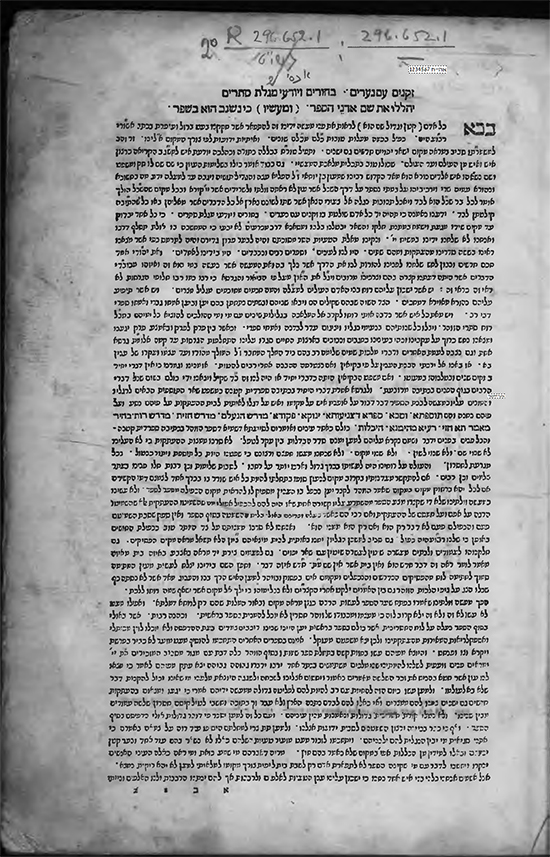

![]()

2. תקופת שקלאוו:

לאחר שכיהן בקאוונא עבר לשרת בעיר שקלאוו. בתקופה זו מצאנו הדים למהרי"ל הקנאי מצד אחד, אבל מאידך מצאנו עדים המעידים על הידיעות הכלליות שרכש ועמדתו החיובית כלפיהן.

בסוף תקופת רבנותו בעיר שקלאוו נתפרסם במכ"ע הלבנון פרטים אודות ביקורו של מהרי"ל באשכנז. אנו למדים מתוך הכתבה שבלבנון, שזמן מה לפני כן נתפרסם בעיתון המליץ "כי הרב הגאון הזה כל מעיינו להוליך את העם בחשך"[16]. כמענה לכך, מדגיש הסופר של 'הלבנון' איך שרבי יהושע ליב היה פתוח מאד להקים בית ספר לתורה ולחכם ברוסיה ופולין. וכך הוא כותב:

מאינץ. כ"א תמוז. – זה שבנו מעיר זאדען אשר הלכנו לשם לראות את פני הרב הגאון הגדול צדיק וענו מוהר"ר יהושע ליב נ"י האבד"ק שקלאב, אשר בא הוא ורעיתו הצדקת והמשכלת תי' לשתות ממעיני מים חיים אשר בזאדען. מאד מאד שבעה לה נפשנו שובע נעימות מראות את פני האדם הגדול הזה, וביותר אחרי דברנו עמו בהענינים הנוגעים לתקון מעמד המוסרי והרוחני של אחינו ברוסיא. ספרנו לו מדבר בית הספר לתורה וחכמה אשר יסד הרה"ג הצדיק מוה' רפאל שמשון הירש בפפד"מ, והבטיחנו כי בשובו דרך פפד"מ[17] יבוא לראות את כבוד הבית הזה, למען יספר באזני אחיו הרבנים הגאונים ברו"פ [ברוסיה ופולין] איך יעזור ה' לחוסים בו המשתדלים לגדל את בני הנעורים על ברכי התורה והדעה, למען יראו וישמעו אחינו ברוסיא ויעשו כמעשה אחינו בפפד"מ. ואחרי שמענו את כל מחשבותיו הטובות והרצויות, אמרנו מי יתן ויכולנו להביא הלום את אלה המבאישים אשר נסו להבאיש את שמן הרקח בשערי 'המליץ', לאמר כי הרב הגאון הזה כל מעיינו להוליך את העם בחשך. – מי יתן והיו האנשים האלה בפנינו כי עתה בכלימה כסנו פניהם בדברם על צדיק עתק. כי האמנם בכל לבבו יחפץ הרב הגאון הנז' אשר אחינו ברוסיא ידעו שפת ארץ מולדתם וכל הידיעות הדרושות לאדם לדעת. אבל בראש כולם יחפץ כי לא תשתכח ח"ו התורה מפי זרענו.

בהפרדנו מלפני הרב הגאון הצדיק הזה, אמרנו בלבבנו: מי יתן ויכולנו לאסוף את אחינו באשכנז לעיר זאדען, למען תאורנה עיניהם מאור פני גאון וצדיק מרוסיא, למען לא יוסיפו לחשוב תועה על כל אחינו יושבי רוסיא כי מרביתם הם כאלה הדופקים על דלתותם לבקש מהם ככר לחם ואגורות נחושת. יבואו נא אחינו האשכנזים עתה לזאדען, יבאו ויראו ויקימו בפניהם ויוכחו לדעת כי התורה והצדקות יחד עם ענוה טהורה תשכון מרומים עוד היום ברוסיא.

מכל אחינו האוהבים את התורה היושבים סמוך לזאדען, נאוה תהלה לאיזה מנכבדי עמנו אשר בפפד"מ כי באו לבקר את פני הגאון הנז' ולשמו ולזכרו תאוות נפשם. גם הגביר הצדיק מוה' זיסקיד הירש אשר הוא עתה בזאדען בקר את כבוד הגאון הזה בביתו.[18]

חודש אחד לאחר מכן, נתפרסמה עוד כתבה בעיתון הלבנון, שנכתב ע"י הסופר אפרים בן דוב ראסקין[19], יליד שקלאוו, ומטרתה להעיד על אמיתת הדברים שבכתבה הנ"ל, ולהבהיר את עמדתו החיובית של מהרי"ל כלפי השכלה כללית. סופר זה מציג את עצמו כאחד משומעי לקחו הטוב של מהרי"ל, בשיעור תלמוד איזה שעות בכל יום, ומהנכנסים אליו בלא בר.

אפרים ראסקין מספר בפרוטרוט אודות הנהגתו של מהרי"ל עם גוים שבאו להישפט בפניו. וכך הוא כותב:

כמה פעמים הייתי בבית הגאון הנ"ל, כשבאו עברים ונוצרים לפניו לבקש מאתו, שיהיה השופט ביניהם, אודות הסכסוכים אשר בעסקיהם, בעת שלא היו עוד שופטי השלום בערי רוססיא הלבנה, כי שמו הטוב הוא מפורסם גם בין הרוססים יושבי המקום, התקין שכל הטענות אשר היו בין העברי והנוצרי יהיו בלשון רוססיא, כדי שיבין הנוצרי מה שידבר ויטעון נגדו העברי, וכאשר בין אחינו אז היה יקר מאוד מי שיבין לדבר בלשון רוססיא, ובפרט לסדר טענות נגד איש ריבו, אשר שפתו שגור על לשונו, אמר שהעברי יעמיד מליץ, שידבר בעדו בלשון רוססיא לפני כבודו, כי הוא מבין בלשון רוססיא.[20]

ולגבי גוף העניין, שמהרי"ל החזיק מעמד חיובי כלפי לימוד שפות זרות וכו',, כותב אפרים ראסקין:

בערדיאנסק. י"ד אב. שנת "התברכו". בעלה 47 – ממ"ע הזאת שנה ט'. קראתי דברי המו"ל על אודות כבוד אדמו"ר, הב הגאון הגדול, צדיק ועניו, מפואר במעלות ובמדות, שונא בצע, הר"ר יהושע יהודא ליב דיסקין נרו יאיר ויופיע. האב"ד משקלאוו עיר מולדתי אשר דבר עמו בנוגע להשכלת אחינו ברוססיא הלבנה, ועד כמה נחוץ ללמדם לשון ושפת המדינה, והנני לקיים הדברים האלה... שמעתי מאדמו"ר כמה פעמים, כי לא טוב הדבר בעינו מה שלא ירגילו בני הנעורים את לשונם לדבר בלשון המדינה, כי טוב תורה עם דרך ארץ. והוא יודע לילך לפי רוח עת החדשה להצמיד האמונה והתבונה ביחד. בתחילת בואו לשקלאוו, פרצה אש המחלוקת בין המתנגדים והחסידים[21], ורבים תלו אשמת המחלוקת באדמו"ר, אשר ידוע כעת לכל אנשי עיר שקלאוו, כי חף הוא מפשע המחלוקת. ואחרי כן כאשר רבים הכירו ערכו ותכונותיו היקרות והנחמדות[22] ונשקעה חמת המחלוקת, קפצה עליו חמת עלילי דברים, כאשר נתפרסם הדברים במ"ע הרוססים, ובמ"ע "היום" בלשון רוססיא שיצא אז לאור באדעססע, כתבו משכילי עיר שקלאוו, והצדיקו את הגאון מהפשעים אשר חפאו עליו. וגם לי ידוע כי נקי הוא מהפשעים אשר עללו עליו, וכל אלה וגם סיבת נפילת מעמד אנשי עיר שקלאוו, אשר נפלו פלאים – ד' ירחם עליהם – עצרו בעדו מלדבר על לב אנשי עיר שקלאוו, שלא ילכו נגד העת החדשה הקוראת בכח. וכפי דברי הרב המו"ל בעלה הנ"ל, הבטיח לו אדמו"ר, בשובו בשלום שקלאווה, יסע דרך פפד"מ... למען בבואו לביתו ידבר על לב נדיבי עיר שקלאוו, להוציא מחשבתו הטובה, אשר הוא חושב, לאור. ולתקן בעירו דבר טוב ומועיל כזה, בית תלמוד תורה אשר מאתו תצא תורה ותבונה ביחד, אמרתי אבא במאמרי זה, לעורר את אחינו בערי רוסייא הלבנה בכלל, ויושב עיר שקאלוו בפרט, לשמוע ולהקשיב לקול העת החדשה הקוראת בכח, לעורר בני הנעורים הנרדמים בחיק העצלות והיאוש, להבינם ולהשכילם כי ערומים הם מחכמה ודעת דרכי החיים. ואקרא! למען יתאמצו ללמוד לבני הנעורים שפת המדינה על בוריה. כי מי כמוני יודע המכשולים אשר יפגשו בני הנעורים אחרי אכלם את לחם העצלות בבית אביהם וחותנם, ואחרי כן כאשר יאבדו הונם בענין רע רח"ל, ואפס מהם כל תקוה לפרנס את ביתם ועולליהם במקום מגורם מוכרחים הם לגלות את עצמם לערי רוססיא הגדולה, הקטנה או החדשה לבקש טרף לנפשם ונפש עולליהם המבקשים לחם בתקותם למצוא שם את אשר יבקשו. וכשהם נודדים בארץ, אז ירגישו ברגש מכאיב לב, המכשולים אשר יקרה להם בארץ נידודיהם, בזה שלא יבינו שפת המדינה, ולא ידעו דרכי החיים, ויקללו את יום הולדם. וגם את הוריהם ומוריהם לא ינקו. [ולאחר שהוא ממשיך לעורר אנשים שילמדו את בניהם שפת המדינה, הוא מסיים:] ואל ראשי החברה כנכבדה "מרבי ההשכלה בין אחינו ברוססיא" ראשי ונדיבי אחינו בארצינו אקרא, שגם אתם תשימו לב על מחשבת הגאון משקלאוו, אשר במחשבתו לעשות, ותתאמצו להיות לעזר להדבר הטוב והמועיל הזאת. ומהנכון שתעוררו את הגאון הנ"ל במכתב פרטי, להציע לפניו את אשר יכשר בעיניכם, לעשות בהדבר הטוב הזאת, ולחזקהו ולאמצהו ולכם תהיה צדקה...[23]

אחיכם המדבר באמת אפרים בן דוב ראסקין, ילידי שקלאוו

מיד אחר הכתבה הנ"ל של ראסקין, יש הערה מהמו"ל אודות התמנותו של מהרי"ל לשרת כאב"ד בעיר בריסק:

בזה הננו לבשר לכל מוקירי שם כבוד הגאב"ד משקלאב הי"ו נ"י, כי נעתר לבקשת עיר ואם בישראל ק"ק בריסק דליטא לשבת בתוכם על כסא הרבנות, [ואף כי צר לו מאד לעזוב שקלאב אשר נפשו קשורה בנפש העדה הקדושה שם, רק מפני רוע אוירה ומצב בריאותו רפה מוכרח לעזוב אותה], ובעוד איזה שבועות יבוא אליהם. בכל לב נברך עדת עיר בריסק כי תשמח היא באיש אלקים הזה אשר זכתה כי יהיה לה לרב והוא ישמח בה עד עולם.[24]

3. תקופת בריסק:

גם בתקופת כהונתו בבריסק מצאנו שתי דמויות הנ"ל משתמשים בערבוביה. המשכילים מאשימים אותו כאיש ההולך בחושך ובאפלה שאינו רוצה להתקדם ולהתפתח. אמנם מאידך מצאנו מגינים עליו ומעידים על השכלתו הכללית.

בעיתון הלבנון מופיע מענה לדברי המשכילים שהתלוצצו בעיתון המגיד[25] על פעילות מהרי"ל בעיר בריסק לחזק את שמירת שבת. המענה נדפס בהלבנון ונחתם בשם 'פל"א' ובו הוא מוחה על שהתלוצצו במהרי"ל, וכדי להצדיק את הצדיק, מזכיר הסופר איך שמהרי"ל אהב גם חכמות:

לא נוכל להתאפק לשים יד לפה מהשיב דבר את המחרף אשר לצון חמד לו, למען בסופרים יתחשב, ותדרוך נפשו עוז, לעלות על במתי 'המגיד' לחרף ולגדף את הגאון הגדול צדיק יסו"ע מוה' יהושע יהודא ליב אבד"ק בריסק נ"י על אשר החזיר העטרה ליושנה להזהיר את בעל חנויות מחלל את השבת. מי יתן ונדע אם המפעל הזה עצר בעד ההשכלה הצועדת קדימה...? האם רוח הפאנאטיזסום לוטה בהמפעל הזה אשר מהר חיש להודיע קבל עם את עון הגאון כי גדול מאוד? מי לא ידע את מצעדי הגאון והלך נפשו אשר הוא אחד מהשרידים האומרים גם לחכמה אחותי את, ודבר שפתיים אך למחסור לדבר אדותו חי נפשי! כי צחוק מכאיב לב היה לנו בראותנו כי ישים אשם נפש הרב, על כי שמשי עיר בריסק הסכינו להזהיר את אנשי המסחר בלשון צלו-דג "זיד פיש"[26] – האם הרב שם בפי השמש את הקריאה הזאת ואל ישנה? דברי פיך יענו בך כי רוח הרעפארם נזרקה בך באמרך כי אחרי בלותו היה להמנהג הזה עדנה, הלא מעולם לא נשבת המנהג הישן הזה מהעירות אשר הסכינו מראש בזה, כי גם היום לא פסקו שמשי מחוז ליטא מלדפוק בכל עש"ק על פתחי החנויות להבהיל את העם לביתם, ומעולם לא מלא רוסי אחד שחוק פיו על המנהג הזה ותהי להפך כי הרוסים הנבונים ישבחו ויהללו את היהודים על כי השבת קודש הו אלמו, ומאשר מפעל הגאון לא יתאים עם מטרת חפץ המתלוצץ והלך נפשו, לכן פער פיו לבלי חוק לתתו ללעג בין כת המכנים את עצמם בשם משכילים אשר כבכורה טרם קיץ כן יבלעו כל מלה אשר תצא מפי רועי צאן יעקב, לחלל כבוד האורתודוקסים ולהתלונן כי לא יבוא כל תועלת ותושיה, רק להזהיר את ישראל מחלל את השבת. אילו בא הרב ותקן בתי-תפלה כתבנית ב"ת הבנוים על אדני הרעפארם, וגם לספח ארגעל אליו, כי עתה פרשת ידיך להלל את הרב הגאון כי שפך רוח עצה וחכמה על העם. תהלה לאל עירות רבות הנה ההולכות קדימה לרוח הזמן. ואשר כפלים להן לתושיה ולחכמה בעיר בריסק, בכ"ז מאד יתעצבו אל לבם בראותם כי הרהיב שועל אחד עוז בנפשו לחבל כרם ד' צבאות ולתת לשמצה את הגאון, ועירנו אחת מהן אשר העירתני לענות את הכסיל כאולתו אשר בא לבער אחר מנהגי ישראל יען כי קנאת סופרים אכלתהו למען הראות לעיני כל כי רוח החופש יתנוסס בו, ויותר הרבה השתוממותנו על 'המגיד' הנושא דגל האמת והשלום, כי הטה אזל לאיש כזה ההולך בשרירות לב ואשר כמוהו כאנשי בריתו יבערו ויכסלו לחשוב כי הציוויליזאציא אור למו ובאמת המה כהמה להם האוכל להאמין כי רק מסוה פרושה על פני המגיד ולבו לא כן? ומאשר לא מצאתי מאומה להצדיקהו אפונה אם לא כנים המה דברי האומרים כי בעל 'המגיד' מתהפך כחומר חותם לכל הצדדים לפי רוח הזמן והעת.[27]

4. אשתו ובנו:

גם אשתו של רבי יהושע ליב [שרה/סוניה], "הרבנית מבריסק", שהייתה מראשי הלוחמים נגד המתחדשים, "הייתה יודעת שפות אירופיות" (אנציקלופדיה לחלוצי הישוב עמוד 565). במקור אחד הוזכר שבנוסף לידיעתה ובקיאותה בתלמוד, שו"ע, ובספרי מוסר ואגדה וכו', ידעה גם עברית, רוסית, צרפתית בדיבור ובכתב. יש הרבה להאריך אודות אישיות מופלאת זו, ואולי עוד חזון למועד.

גם בנו יחידו מאשתו הראשונה, הגאון רבי יצחק ירוחם, ידע לדבר בכמה לשונות. בספר "דורות האחרונים" (עמוד 111 ערך דיסקין, ירוחם יצחק), מתואר ריי"ד כ"גאון גדול וחריף, מופלא במדע ויודע לשונות".

למרות שקיצרתי בענין השכלתם הכללית של אשתו ובנו של מהריי"ל דיסקין, אעתיק כאן מהספר 'בתוך החומות' מאת 'מנחם מנדיל פרוש' לגבי השכלתו הכללית של רבי יצחק ירוחם. בראשית דבריו מתארו הסופר הנ"ל כ"אישיות גאונית ופלאית ורבת הסתירות"[28]. אך הסופר הנ"ל מרחיב הדברים וכך כתב:

כשהופיע בירושלים בשנת תרס"ז עפ"י דרישת גבאי ומנהלי המוסדות שיסד אביו הרב מבריסק מוהריי"ל זצ"ל, לא נתקבל מאת ראשי ומנהיגי העיר בכל הכבוד הראוי לו, אולי משום... וגם מפני... גם אחרי שבא ירושלימה, הסתיגו ממנו הת"ח והלומדים מפני צורתו החצונית ותלבושתו המודרנית אף שמעו עליו שיודע שפות זרות רוסית וצרפתית גם יש לו ידיעה במדעים חצוניים ויודע פרק בחוקי משפט של נכרים כמו עורך דין, ביחוד נרתעו בני ירושלם כששמעו שאשתו לובשת פאה נכרית עם כובע אירופית...[29]

בהמשך מזכיר הסופר הנ"ל התנגדותם של הקנאים הקיצונים, בייחוד של כולל אונגארין, שנמנעו "מלדרוך על סף בית הגריי"ד [=הגאון רבי יצחק ירוחם דיסקין] עד זמן מחלוקת הרבנות שאז נצלו את שמו והכתירו אותו לנשיא עדתם."

מעניין שגם בעניינו של רבי יצחק ירוחם חוזר ונשנית התיאור 'אריסטיקרטי' שמצאנו אצל כמה מבני משפחתו. וכך כותב הסופר פרוש הנ"ל:

מין אצילות אריסטיקרטית מהספירות הגבוהות היה חופף עליו שהטיל חרדה נעלמה ובלתי מבוררת יחד עם הדרת הכבוד על כל איש רציני בעל כובד הדעה שנגש אליו.[30]

דברים מרחיקי לכת אודות נטייתו של רבי יצחק ירוחם לציונות ראוי להעתיק כאן מפני שאם כנים הדברים יהיה בזה צד השווה בינו לבין דודו הרב נח יצחק שהיה מחובבי ציון. וכך כתב פרוש:

בעיר אומן מקום שהיה גר שם [רבי יצחק ירוחם] שנים רבות ושם נשא אשתו השניה מרת ינטה עה"ש היה שם מהציונים הראשונים, וד"ר הרצל פנה אליו במכתב ובקש ממנו שיעמיד את עצמו בראש התנועה הציונית במחוזו.[31]

הכי מעניין הוא טענת פרוש שאשתו העשירה [ינטה] של רבי יצחק ירוחם הייתה הסיבה מדוע התנגד להרב קוק, שכן טענה זו ממש טענו מעריכי אביו רבי יהושע לייב שהתנגדו לפולמוסים שלו, שאשתו הגבירה [סוניה] הייתה הסיבה לכך. וכך כתב פרוש:

חלק גדול בהתנגדותו [להרב קוק], היתה לאשתו שכיבדוה מאד, היתה ממשפחה עשירה, ודעתה היתה זחוחה עליה, ועזרה במסירות רבה בכלכלת בית היתומים וגם היותה דעתה בכל עניני ההנהלה והיא הקפידה הרבה על כבוד בעלה. זכורני שפעם כאשר בא רבינו [אברהם יצחק הכהן קוק] מיפו ירושלימה וביקר מקודם בבית הרב רבי חיים ברלין ז"ל התרגזה עד כדי כך שאמרה שלא תעזוב את רבינו [קוק] לבוא לביתם, ובקושי עלה לפייסה עד שתנוח דעתה.[32]

עוד בענין השכלתו הכללית של מהרי"ל, ראה כאן וצפו כאן.[33]

נספח ב

יחסם להשכלה כללית של שאר בניו וחתנו של רבי בנימין דיסקין

לאחר שהראנו כיצד דמויותיו של הרב יהושע ליב בחוצה לארץ אינה שחור לבן, ושהיא שונה היא לחלוטין מזה שאנו מכירים בירושלים, ראוי למלאות את דברינו על ליקוט פנינים כאלה אודות בני משפחתו הרחבה. כל עובדות הללו מצביעים בכיוון אחד, והוא מה שכבר הראנו בחלק ראשון של מאמר זה, שאבי המשפחה, הרב בנימין מהורודנה, הנחיל דמות של גדלות מופלאה בתורה ממוזג עם השכלה כללית ואריסטוקרטיה.

ונתחיל עם האח של מהרי"ל, הרב נח יצחק:

1. הרב נח יצחק דיסקין מלומזה

בספר עץ חיים (שו"ת ממשפחת אבלסון עמוד פב) מתאר הרב אברהם יואל אבעלסאהן את רבי נח יצחק "הגאון המפורסם זך הרעיון החכם הכולל ר' יצחק דיסקין", ואילו מהרי"ל דיסקין עצמו מתואר בשם "הגאון אריה דבי עלאי צי"ע". רואים מכאן שביחד למהרי"ל היה ר' נח יצחק יותר עולמי ומפותח עד כדי כך שהתואר "החכם הכולל" הולמתו במקום שהתואר "אריה דברי עלאי צדיק יסוד עולם" הולם את האח הגדול.

כמו כן בספר ה'סבלוני' מאת אביו של הגרי"א הרצוג, הרב יואל ליבוש הרצוג מלומזה (ווארשא, 1890) כותב המחבר הנ"ל שבמקום לקחת הסכמות על ספרו "הראתי את כתבי לכבוד הרב הגאון הגדול כליל החכמה והמדעים שלשלת היוחסין כקש"ת מו"ה ר' נח יצחק דיסקין מלאמזא וגם לכבוד הרב הגאון הגדול צמ"ס [צנא מלא ספרא] שלשלת היוחסין כקש"ת מו"ה ר' אליהו דוד תאומים מק"ק פאניוועז...". (אני מודה לפרופסור מלך שפירא שהפנה אותי לספר ה'סבלוני')

מלבד היותו "כליל החכמה והמדעים" היה רבי נח יצחק נמנה "מחובבי ציון" (אישים וקהילות עמוד 384 – הרב משה צינוביץ). ובאנציקלופדיה של הציונות הדתית (ערך דיסקין, נח יצחק) כתוב שהיה פעיל בתנועה זו, וגם השתתף באסיפותיהם של "חובבי ציון" בלומזה ואף נאם שם. מעניין, שהוזכר שם שהקנאים הקיצוניים שבעיר נאלצו לשתוק על פעולתו זו, משום כבודו של אחיו רבי יהושע לייב דיסקין, ראש הקנאים בירושלים. ראה שם עוד פרטים בעניין זה.

בספר זיכרון של קהילת לומזה (אכסניה של תורה עמוד 109) נזכרו כמה פרטים אודות רבי נח יצחק המזכירים מאד את דמות אביו, רבי בנימין. כתוב ש"רבי נח יצחק היה אדם יפה-תואר, הדור בלבושו, אציל הרוח ונוח לבריות. בדיני תורה ו'שאלות' היתה דרכו להקל. בחוגי הממשלה כבדוהו לרגל תלבושתו המהודרת וכובע צילינדרו המבריק, והציגו אותו דוגמא לעומת רבנים אחרים, מסביבות לומזה, שהיו באים אל השלטונות כשאינם לבושים כהוגן ורבבים על בגדיהם."

כבר ראינו למעלה שימוש בכינויים אלו 'החכם הכולל' ו'הדר בלבושו' גם על רבי בנימין. כמו כן ראינו אגדות המקשרים רבי בנימין עם הממשלה.

עוד הובא (שם) בשם המצייר בוגאצקי שהיה אומר "לצייר צורתו הפטריארכלית של ר' נח יצחק דרוש לי המכחול של ראפאל או רמבראנד". ובשם רבי טוביה פנסטר שהיה מרואי פני רבי נח יצחק הובא שם, שכשהיה דרוש לפנות אל הבארון רוטשילד הפראנקפורטי בדבר ענין ציבורי, נבחרו למטרה זו בפולין שני רבנים מפורסמים ובראשם רבי נח יצחק, שידע היטב את השפה הגרמנית.

רבי יצחק אייזיק הלוי הרצוג (ספר זיכרון לקהילת לומזה – רשומות עמוד 323), יליד לומזה, הקהילה אשר בה כיהן רבי נח יצחק כראש בית דין, מספר שהיה מצוי הרבה אצל הג"ר נח יצחק דיסקין זצ"ל, הואיל ואביו [של רבי יצחק אייזיק] הורה ודן אתו יחד משך חמש שנים. אצטט כאן מלשונו של רבי יצחק אייזיק, אשר לימים היה רב הראשי לישראל:

[הרב נח יצחק] היה טיפוס מעניין. הוא היה בנו של הגאון רבי בנימין דיסקין זצ"ל ואחיו של הגאון רבי יהושע ליב דיסקין הידוע כאן בירושלים בשם הרב מבריסק ז"ל. התענגתי מאוד לשמוע שיחותיו הנעימות מתובלות בדברי תורה ובזכרונות על אחיו שבירושלים עיה"ק, על גאונותו המפליאה ועל חסידותו המופלגת. ועל אביו רבי בנימינק"א, ועל הגאון [רבי יצחק אלחנן] מקובנה שלמד אצלו [= אצל רבי בנימינק"א] בגרודנה [אולי כוונתו לוואלקאוויסק פלך גרודנה] שלוש שנים. כשהייתי בן שמונה והתפללתי בשבת עם אבא זצ"ל במנינו הפרטי, כיבדני לדרוש, אחרי קריאת התורה. לאחר סיום דרשתי נשקני על ראשי ואמר: אע"פ שאין מנשקים בבית הכנסת לילד כזה מותר.

והראה לי פרופסור מלך שפירא שבספר 'אמרי יואל' (בראשית, עמ' 200) מאת אביו של הרב הרצוג, ישנו הספד שנשא על הג' ר' משה יהושע יהודה ליב דיסקין, ובראש ההספד מזכיר הרב הרצוג ש"גזר עלי אחיו הגאון ר' נח יצחק ראב"ד דק"ק לאמזא ז"ל להספידו כהלכה בבית המדרש הגדול אשר שם התפלל ודרש. והנה כאשר המקום היה צר לכן הוציאו כל הספסלים החוצה וכל העם מקטן ועד גדול עמדו על רגליהם כל העת, המחזה לעצמה הייתה נוראה וזאת אשר דרשתי..." עוד הראה לי שבספר הנ"ל (שמות, עמ' 28, וחלק ד עמ' נו ועמ' קנג) מזכיר הרב יואל הרצוג דברי תורה וסיפורים בשם רבי נח יצחק.

אנו מוצאים כתבה מעניינת בעיתון הצפירה (מרץ 11, 1879 עמ' 67) אודות רבי נח יצחק המעידה גם כן על ידיעותיו הרבות ועל נועם הליכותיו. מי שחותם את שמו 'הירש פערלא, מורה בטשענסטאכויא', מתלונן שם שכבר עברו איזה ירחים מאז נתקבל רבי נח יצחק לשמש כרב אב"ד בעיר טשענסטאכויא, ועדיין לא קיימו העיר את מוצא שפתיהם למנות אותו כרב. המורה הנ"ל מתאר איזה מין רב דרוש לעירו:

אשר מלבד תורתו וחכמתו, יהיה גם איש טאלעראנטי היודע לנהג את בני עדתו בשלום ובמישור; רב היודע לתווך בין סוחר לסוחר בכל עניני מסחר וקנין בדעת ותבונה, ולפשר ביניהם בדברים כבושין ובחכמה; רב אשר יוכל לשאת מדברותיו בדרושיו המחוכמים בדברים פשוטים המובנים לכל ההמון כו' וכו' לנו נחוץ רב היודע ומבין לבד השפות רוססית ואשכנזית, גם שפת פולאנית, כי לבד הפולאנים הרבים הגרים פה, ואשר רוב עסקי היהודים פה סובבים על אופניהם, עוד רבים מבני ישראל בעירנו ידברו גם הם רק שפת הפולאנים. והרב אשר אלה לו, יוכל לקנות לו את לב בני עדתנו, לאהבה אותו בכל לבבם. וכל המעלות האלה נמצאו בהרב הגאון רנ"י דיסקין מלאמזא, אחד לא נעדר. לבד יחוסו הגדול מאביו זצלל"ה, ומכבוד אחיו הגאונים הגדולים והמפורסמים בכל הארץ...

ובשולי הגיליון של הצפירה מעיר המו"ל, חז"ס, שהוא עצמו הכיר את רבי נח יצחק דיסקין באופן אישי מתקופת למדו אצל אביו של רנ"י, והעיד חז"ס שכל השבחים שנאמרו אודות רבי נח יצחק אמתיים הם.

מעניין מאד שבעיתון 'חבצלת' (פברואר 9, 1898) מדווחים ש"קרובי ומקורבי הרב הגאון המנוח מוהר"ר משה יהושע יהודא ליב זצ"ל, בקשו את אחיו הרב הגאון מוהר"ר נח יצחק דיסקין נ"י אב"ד בלאמזא, לבא ירושלימה, למלא מקומו, ולעמוד בראש מוסד החסד בית היתומים אשר יסד, כפי הנשמע נעתר הרב הגאון הנ"ל לבקשתם ויודיעם בטע"ג [טלגרף] בשבוע הזה, כי יבא ירושלימה. מכירי הרב הגאון הנזכר מהללים אותו כי חכם גדול הנהו ודעתו מעורבת עם הבריות."

2. רבי זרח דיסקין מהורודנה

למרות שלא מצאתי כל כך מידע אודות הרב זרח דיסקין, מכל מקום זה ברור שלא היה קנאי ואף הראה פנים מסבירות לציונות (אישים וקהילות שם). לאחר פטירת רבי זרח הופיע בעיתון הצפירה (ספטמבר 14, 1914) מודעה זו:

הגאון ר' זרח דישקין ז"ל

ביום ו', י"ג אלול, נפטר בעירנו הגאון המפורסם ר' זרח בהגאון ר' בנימין דישקין זצ"ל.

המנוח היה אחד מארבעת האחים הגאונים הנודעים שהיו תפארת לישראל: ר' יהושע ליב מבריסק, שהיה אח"כ רב בירושלים, הגאון ר' שמואל, שהיה רב בוולקוביסק, והגאון ר' נח יצחק אב"ד בלומזה. הגאון ר' זרח היה המוהיקני האחרון [The last of the Mohicans] במותו פסקה הרבנות הגאונית, חכמת ישישים ובטלה השקדנות. המנוח היה למדן ושקדן שאין דוגמתו. מבן חמש עד יום מותו לא הניח הספר מידו. בנעוריו נסה להיות סוחר, אבל עד מהרה נוכח, שאין המסחר יכול להשביע רוחו הגדול ואת לבו הרחב, ויפן אל הרבנות, ויהי רב בהורודנה, באותו הפרבר, ששם כהן פאר אביו הגאון ר' בנימין זצ"ל, כארבעים שנה. בדעתו את העולם ובחכמתו הרבה ידע להתהלך עם הבריות, ויהי אהוב ומכובד על כל איש. עונג וקורת רוח היה לאיש שישב בחברת המנוח ושמע שיחותיו הנעימות והערבות, שיחות תלמיד חכם מתובלות בזיכרונות דברי הימים, כי המנוח הצטיין גם בכח זיכרון עמוק ונפלא, עם גדלו בתורה ויראה לא היה קנאי אדוק, לא השמיע תוכחה, בדעתו שאין לשחות נגד הזרם. בשנת תרכ"ב הוציא בקניגסברג את ארבעת הטורים עם ביאור נפלא משלו. ומאז כתב הרבה ולא הדפיס, באמרו, "דייני שאני יודע שאינני למדן". במות אחיו הגאון ר' יהושע ליב בירושלים, פנו אליו יקירי ירושלים בהצעה לרשת את כסא הרבנות בירושלים, אבל המנוח בהיותו רחוק מריב מפלגות ומפני זקנתו המופלגת דחה את ההצעה.

בן תשעים ושלש היה במותו. לא כהתה עינו ולא נס ליחו. זקנתו המופלגת לא עצרה כח להכריע את רוחו הגדול. המנוח לא עזב את הספר עד רגעו האחרון, ויהי באמת מזקני תלמידי החכמים, שכל זמן שמזקינים דעתם מתישבת עליהם.

להלויתו, שהיתה ביום הראשון, ט"ו אלול, נהרו אנשים לאלפים.

תנצב"ה.

ידידיה ינובסקי

3. הרב ישראל אברהם שמואל מוילקובסיק

כל ארבעה אחים מילאו מקומו של אביהם, מהרי"ל מילא מקומו בלומזה, רבי נח יצחק גם כן מילא מקומו בלומזה, רבי זרח בהורודנה, ורבי ישראל אברהם שמואל שהיה בעל מחבר ספר 'לבני בנימין' מילא מקום אביו בעיר וולקוביסק. למרות שבדרך כלל לא התערב הרב אברהם שמואל בענינים ציבוריים, יש ממנו מכתב הנדפס במוריה (שנה יח, גליון ג) בו הוא משתדל לבטל גזירת הממשלה שאיימה על עמדתם של הרבנים המסורתיים, ומתלונן על 'הגאון מקאוונא', שלא התערב עד אז. וכך הוא כותב לידידו הגאון רבי מרדכי גימפל אב"ד רוזאני, "מכתב קדשו הנורא הגיעני כרגע קראתי בשברון מתנים, אהה ד' אלקים כלה אתה עושה לשיור התורה הזאת. שאלה אחת אשאלה מכת"ר, מדוע יחשה הגאון מקאוונא, הלא הוא היה ראש המדברים בשאלת היהודים הכללי, וכאשר לא נמניתי עד היום בארצינו בכל דבר הכלל ולא נודע שמי, דעתי להוחיל עד בוא דבר הרב מקאוונא שליט"א". בתוך דבריו מציע הג"ר אברהם שמואל שהוא עצמו ייסע לדבר לפני השר ומתפאר בעצמו שהוא ראוי לכך, "ואני כאשר הייתי בפאריז לא עמדו לפני כל חכמיהם ומלומדיהם כי מצאו בי עשר ידות בכל השלמות אשר המה מתהללים בהם ולא נעלם ממני כל אשר שאלו ממני". רואים מכאן שמצד אחד השלים עצמו בחכמות, אבל היה מקנא קנאת ה' לבטל גזירת המשכילים.

מצאתי עוד פרט אודות רבי אברהם שמואל הנוגע קצת לענינינו, והוא מדברי הרב הראשי רבי יצחק אייזיק הרצוג ז"ל (תחומין ו, עמ' 311) בשם אביו:

מאבא מארי ז"ל שמעתי שהגאון ר' אברהם שמואל דיסקין ז"ל, רבה של וילקוביסק פלך גרודנא, (נפטר קרוב לחמשים שנה בערך), מחבר ספר לבני בנימין, היה גדול בשחמט ושחכמתו זו עמדה לו להנצל מצרה.

4. שרה דבורה רוזנברג

לארבעה אחים הנ"ל היתה גם אחות ושמה שרה דבורה. היא הייתה אשתו של רבי אליהו רוזנברג. רבי אליהו היה סוחר משכיל, מפורסם בעשרו ומופלג בתורה (ישראל לוינסקי, ספר זיכרון לקהילת זאמברוב עמ' 458). בספר זיכרון לקהילת לומזה (עמ' 126) כתוב שרבי אליהו דאג שחתנו ר' עקיבא רבינוביץ ילמד גם לימודי חול, רוסית ופולנית גרמנית ורומית. בראשית דרכו של חתנו הנ"ל, הוא היה רב מטעם, ואחד מהרבנים של חובבי ציון. לאחר מכן נעשה מקורב לרבי שמואל מוהליבר שהמליץ לפני קהילת פולטאווה למנותו בה לרב. אולם בעת ועידת חובבי ציון בווארשה נהפך לב רבי עקיבא והפך להיות מתנגד חריף לתנועת ציון, ויסד את ה"פלס" ומלא אותו במאמרים נגד הציונות.

היה גם נכד לרבי אליהו, שקראו לו בנימין, ואותו לקח הסבא ר' אלי' רוזנברג לווארשא, ושם למד תלמוד ומפרשים אצל מלמדים מובהקים וגם השכלה. סבא שלו שכר לו מורים טובים למתמטיקה, עברית, לשון המדינה ושפות אירופה (ישראל לוינסקי שם). יש סיפור מעניין אודות ר' אליה בספר זיכרון לקהילת לומזה הנ"ל:

ר' אליה רוזנברג היה חתן הרב ר' בנימין דיסקין והצטיין בחריפותו ותבונתו. כאשר עזב ר' י"ל דיסקין, גיסו, את לומזה ועבר למזריץ', בשנת 1859 בערך, נשאר הוא הדיין והמורה צדק בלומזה, שלא על מנת לקבל פרס. ר' אליהו היה מעשירי לומזה, סוחר ישר ומפורסם וגם פטריוט פולני וכפי מה שמסופר ב'כרמל' (שנה ב' עמ' 10) ערך ר' אליהו אזכרה בבית המדרש הגדול ביום כ' תמוז תרכ"א (1861) למותו של החכם הסופר הפולני יואכים לאלאוויל. באותו יום בבוקר נערכה אזכרה בבית התפילה של הקאפוצינים ומשם הלכו כולם אל בית המדרש הגדול. השתתפו נוצרים רבים, כוהני דת ופקידים גבוהים. הרב דמתא הספידו פולנית מעל הנייר ואחריו ניגן "אל מלא רחמים" ופרקי תהילים החזן ר' אברהם משה בלושטיין שהפתיע הנוכחים הנוצרים בקולו החזק.

סיכום אודות משפחת דיסקין

נראים הדברים שיוצאי בית מדרשו של רבי בנימין דיסקין נהנו מידיעותיו בעניני העולם, כגון אסטרונומיה, אלגברה, ועוד חכמות. יתכן מאד שבתחום הזה השפיע רבי בנימין על חז"ס שיתקדם בלימודים הללו. כמובן, שרבי בנימין לא היה מרחיק לכת כמו חז"ס, אבל התמונה החדשה שהצגנו כאן אודות רבי בנימין, בני משפחתו, ויוצאי בית מדרשו, נותן קצת קונטקסט לחז"ס. אין הכוונה, שאישיותו של חז"ס דורש קונטקסט, הלא רבים מבני דורו עזבו בית מדרש הישן ודבקו בדרכים החדשים של אסכולת ההשכלה, אבל מאחר שאנו רואים איך שחז"ס בראשית דרכו כתב ספרים דווקא על הנושאים שהיה רבו בקי בהם, ומאחר שאנו רואים שחכמת המדעים ודברי ההשכלה לא היו כל כך רחוקים מדרכי משפחת דיסקין עצמם, הרי יש לנו קונטקסט בין אם יש צורך בכך או לא. הראנו איך שחז"ס מתגאה בזה ששקד על דלתי רבי בנימין וגם מעיד על היכרותו עם בני רבו. והבאנו דברי נכד מהרי"ל שהצביע על חז"ס כעדות על השכלת רבי בנימין, אבי סבו. אך לא מצאנו קשר ישיר בין מהרי"ל וחז"ס, שכן לא נתקבל אצלנו העובדה שחז"ס ביקש הסכמה ממהרי"ל, אבל מצאנו אולי מקום אחד שינק מהרי"ל מחכמת חז"ס שבספרו מציאות הנפש.

נספח ג

הסכמות מרבי אבלי לספרי משכילים

בקשר להסכמת רבי אבלי לספרו של חז"ס, ראוי להזכיר שחז"ס לא היה המשכיל הראשון שקיבל הסכמה מרבי אבלי. רבי אבלי כבר הסכים על הספר 'תעודה בישראל' שש שנים לפני שהעניק הסכמתו ל'מוסדי חכמה'. הספר 'תעודה בישראל' חובר ע"י ה'מנדלסון הרוסי' יצחק בר לוונזון[34] המכונה ריב"ל, וכך כתב הרב אבלי בהסכמתו:

קול התורה נשמע בארצנו, וזמיר החכמה הגיע עדינו, כי נראה קסת הסופר בימינו, ספירת דברים דברי חכמה ובינה, כמסמרות נטועים וכדרבונה, פעמי שולמית בתורה ובחכמה להכינה, ומה הדרבן מכוון להביא חיי העוה"ז אף דברי חכמים הגם שעיקרן לחיי עד עם כל זה בחכמתם מכוונים גם חיי עוה"ז לכוננה, ולכן נקראו אבות שגם הם מביאים לחיי עוה"ז כמו האב. אפס כי לא רבים יחכמו ללקט מפניני פנימה אמרות טהורות ללבות דברים כגחלי אש, אשר אם לבה מלבה והיה לאש בוערת, ואשר הם כחדום בלשונם לשון זהב ואדרת, לזאת יקרו בעיני מאד מליצינו ורעינו, אשר לטובת בני עמינו, בחבורתם נרפא לנו, לרפאות משבח ה' ההרוס כי יוסיפו לספר בשבח האר"ש ארשנ"ו הרעננה ארשת שפתינו, שפת לשון עבר ואשורית, זכה וצחה מלובנת בקמוניא אשלג ובורית, וילמדנו דעת סדר הלמוד ללמד לבני יהודא, לתורה ולתעודה, בישראל שמו, כי העד העיד בעמו, ויתן אומר אמרי שפר, ככל הכתוב פה בספר, לשובב נתיבות ולגדור פרץ, בלמוד התורה והחכמה וגם בדרך ארץ, ויישר לישורון הדרך הנכוחה, לדעת לשון וספר ולאחוז במלאכה, או במסחר הראוי לעשות ככה, ולדרוש שלום העיר המחוז והפלך, ולעשות הטוב והישר בעיני אלקים ומלך, ויחזק חרש זה כל דבריו את צורף באמרות ה' הצרופות, או בדברי חז"ל בעלי אסופות, הן כל אלה פעל ועשה גבר חכם בעוז, יקר מפז, החכם המפואר ותורני מופלג הרב מו"ה יצחק בער מקרעמניץ יצ"ו, חזיתי איש מָאור מעיר במלאכתו לפני מלכים יתיצב, גזרתו ספיר אבן מחצב, וספרו זה ראו חכמים ויאשרוהו, שרים ורוזנים ויהללוהו, סופרים הביטו ונהרו, ומשוררים יצאו לקראתו ושרו, עד שעלה והגיע למרום מצבו, כי עד מקום שאדונינו הקיר"ה במסבו, הובא להתבונן בו מה טיבו, ויחוננהו הקיר"ה כרוב נדבת לבו, למען יצא לאור לראות באבו, הן מאן חשוב ומאן ספון ומאן מעייל אזובי הקיר, לא ראו אור בהיר, אך אחרי שה"ה הרב החכם השלם הלזה גם אותי דרש במכתבו הרמה, חפצו הטוב והישר להשלימה, לזאת אמרתי לענות אחריו אמן בכל כחי, ולהגיד לו באמת משפט לבי ורוחי, ובאין משוא פנים אמרי ושיחי, כי נחת"תי בספרו זה ויהי לריח ניחוחי, והנני לקבל ספר אחד במחיר הקצוב וגם לעורר נדיבי עמנו לקחת לקח טוב כי מוצאו מצא טוב, ויפק רצון מה', כרצון המחבר מלב ורצון תמים מעתיר לראות בגויות ברמים, היום יום ב' ו' מרחשון קחו דעת לפ"ק, פה ק"ק ווילנא.

נאום אברהם אבלי בהרב המאו"הג מהו' א"ש זצ"ל

קשה לראות בהסכמה זו שום דבר אחר, מלבד הסכמה נלהבת לספרו המשכילי של ריב"ל. ואכן בנוסף ל'תורה שבכתב' הנ"ל מאת הרב אברהם אבלי, יש לנו גם 'תורה שבעל פה' המעידה על מבטו החיובי של הגאון רבי אברהם אבלי על הספר ה'תעודה בישראל'.

מ. ליפסן מספר:

כשהוציא רבי יצחק-בר לווינזון, הריב"ל, את ספרו "תעודה בישראל" נתקבל הספר בכל תפוצות ישראל ורבו המעיינים בו.

שאלו לרבי אבלי מפוסביל: ספר "תעודה בישראל" מהו בעיני רבנו?

ספר זה – אומר רבי אבלי – חסרון אחד יש בו.

חסרון זה מהו? – שואלים אותו.

חסרונו, - משיב רבי אבלי – שהגר"א מווילנה לא חבר אותו...[35]

סיפור זה הובא גם ע"י מ. אשעראוויטש[36] עם תוספת ביאור, כלומר, שכוונתו של רבי אבלי הייתה שספר כמו התעודה בישראל אפילו הגאון מווילנה היה מחברו.[37]

ברם, ר' דב אליאך מתקשה להבין כיצד יתכן שרבי אבלי – אחד מגדולי הדור – יסכים על ספרו של ריב"ל – 'המנדלסון הרוסי'. ומתוך כך בא לידי מסקנה שלא מרצונו הטוב עשה רבי אבלי כן, אלא שאימת המלכות הייתה רובצת עליו. וכך הוא כותב:

לריב"ל זה היו מהלכים במסדרונות השלטון, והוא נעזר בו רבות למימוש מזימתו. ראשי השלטון שראו ברעיונותיו פתרון מתאים לעתיד היהודים בני חסותם, נאותו להקציב לו סכום כסף נכבד לשם הוצאת ספרו, והדבר צויין על ידו בהקדשה מיוחדת בראש הספר. מה תימה אפוא, אם חתימת הג"ר אבלי, מגדולי הפוסקים בימיו, מתנוססת בראש הספר, אחר שריב"ל נזקק לה כדי לקבל אישור ותוקף לחיבור. אימת השלטון הצארי פעלה כאן את פעולתה.[38]

הרב אליאך[39] מפנה את הקורא לספר 'רבינו אליהו מווילנא' שהעיד שזה היה דבר ידוע בקרב זקני ווילנא שרבי אבלי עשה כן בבחינת אנוס על פי הדיבור. וכך כותב יצקן:

כלנו יודעים את כל המסופר אחורי התנור בבתי המדרש[40], על דבר הסכמתו של רבי אבלי פאסוולער על הספר "תעודה בישראל" להריב"ל, שזה אחד מהדברים הסתומים שזקני ליטא כבר דרשו עליו תילי תילים של אגדות וסיפורי מעשיות. איך ובמה הגיע לכך. זה יספר לדבר ברור לפי המסורת הנאמנה שבידו כי רבי אבלי עשה זאת רק מפני שלום מלכות, מאחר שהקרמיניצר [כינויו של לוינזן שגר בקרמניץ] היה מבאי ביתו של הקיסר ניקולאי הראשון כידוע, ולוּ לא נתן רבי אבלי את הסכמתו על ספרו, כי אז הלא יכול היה להביא שואה על כל בית ישראל חלילה. וזה מספר כי רמזו לו ממקום גבוה. ורבי אבלי כתב בדמע. אבל בין כך ובין כך הכל מודים, ואין אף ספק אצלם, כי רבי אבלי לא היה נותן את הסכמתו על "התעודה" בלתי איזו סיבה חיצונית שהביא לכך. ומעשה באחד מזקני המוצי"ם שבוילנא, שקרא תגר על אחד מתלמידיו, על שנמצא אצלו 'התעודה'. ויתאמץ הצעיר להתנצל ולהצטדק בזה, כי הלא רבי אבלי נתן הסכמתו עליו. ויתמרמר הזקן ובחמת רוחו הכהו על הלחי לאות ולחרפה על שאלתו הנבערה, "הטרם תדע", קרא המו"צ בשצף קצף, "כי לא מדעת עצמו נתן את ההסכמה הזאת? [מעשה שהיה לפני שנים אחדות, ועדים חיים אתנו כהיום, שמוכנים להעיד על אמתת הדבר]"[41]

ברם, כל הסיפורים והאמתלות האלו יכולים להתקבל על לבו של מי שמעולם לא ראה את הסכמתו של רבי אבלי, אבל מי שבאמת קרא הסכמתו של רבי אבלי, לא ישתכנע מסיפורים אפולוגטיים כאלה. שהרי מי שהוא אנוס ע"פ הדיבור אינו חייב להעניק הסכמה כל כך חמה ושופעת חן. אין זו הסכמה שנכתבה 'בדמע'. כמו כן מתעלם הרב אליאך מהעובדה שרבי אבלי העניק הסכמותיו גם לספרו של חז"ס וגינצבורג[42]. ומה שיצקן מספר שהיה אנוס על פי המלכות, למרות שיש אולי רגליים לדבר מהעובדה שהקיסר השתתף בהוצאת הספר 'התעודה בישראל', מכל מקום הלא חכם עדיף מנביא, וכבר ראה מזלו של רבי אבלי, שיבואו אלו ויהרהרו שבלא לב ולב כתב הסכמתו, ולכן הדגיש רבי אבלי בהסכמתו, שלא כן הוא פני הדברים, אלא שהוא כותב כן 'באמת'. רבי אבלי מדגיש שלא הלחץ מאת הקיר"ה הפעיל עליו, אלא למרות שהספר "עלה והגיע למרום מצבו, כי עד מקום שאדונינו הקיר"ה במסבו, הובא להתבונן בו מה טיבו, ויחוננהו הקיר"ה כרוב נדבת לבו", הוא עצמו רוצה "להגיד לו באמת משפט לבי ורוחי, ובאין משוא פנים אמרי ושיחי, כי נחת"תי בספרו זה ויהי לריח ניחוחי."

עדותם של 'זקני ווילנא' שנמסרה יותר משבעים שנה לאחר המעשה, אינה מתקבלת כלל נגד מכתב ברור. וגם ה'הוכחה' שהביא אליאך[43] על השקפתו של רבי אבלי הנלמדת מתוך הסכמתו לספר איל משולש, אינה ראויה להשיב עליה. רבי אבלי כתב בהסכמתו להדפסת הספר 'איל משולש' שחובר ע"י הגר"א, ואשר נושא הספר הוא חכמות ההנדסה, האלג'ברה ותכונה, ש"ראוי ונכון לפרסם חכמת הגאון [רבינו אליהו מווילנה] זללה"ה, למען ידעו רבים, כי חסידי ישראל הם חכמים אמתיים, וחכמתם עמדה להם לעבודת השי"ת ב"ה". לדעת אליאך רואים מזה שבעיני רבי אבלי "כל חשיבות הדפסת הספר אינה אלא למען ידעו הרבים, כי חכמת גדולי ישראל עמדה להם לעבודת ה', והם הם החכמים האמתיים, אבל לדברי הספר הזה, כמו לחכמות בכלל, אין כל ערך עצמי ומהותי, המחייב לקרוא לציבור הרחב לעסוק ולהתמיד בהם".

קשה לקבל 'דיוק' לשון כזה בדברי רבי אבלי, שהרי בין בהסכמתו לספר 'התעודה בישראל' של ריב"ל, ובין בהסכמתו לספר 'מוסדי חכמה' של חז"ס, ברור מללו שרבי אבלי חשב שהפצת החכמות היא דבר חיובי מצד עצמה ולא רק "למען ידעו הרבים כי חכמת גדולי ישראל עמדה להם לעבודת ה' והם הם החכמים האמתיים". דברי רבי אבלי בשתי ההסכמות הללו מוחקים את התמונה שצייר אליאך. אין אנחנו חייבים לקבל את האגדה של ליפסן שרבי אבלי הגזים שהגר"א היה ראוי לחבר 'התעודה בישראל', אבל לעומת זה איננו יכולים לקבל האגדה בשם 'זקני ווילנא' אשר כאילו רבי אבלי כתב את דבריו כמי שכפאו שד.

מעניין לעניין, ראוי להזכיר, שגם בנו של הנודע ביהודה, "הרב הגאון הגדול החכם השלם הגביר המפואר הדר עמו ותפארת לאומו, גבר חכם בעוז לפני מלכים יתייצב כבוד מוהר"ר יעקבקא לנדא נ"י"[44] דיבר בשבח הספר במכתב שנתפרסם ע"י ריב"ל בספרו הנ"ל מיד אחר הסכמת רבי אבלי.

[1] רבי מרדכי גימפל (1820-1891) היה רבה של העיירה רוז'נוי שברוסיה הלבנה ועלה לארץ בשנת תרמ"ח (1888).

[2] בשולי הגליון כתבו עורכי 'אוצרות ירושלים': אולי צ"ל חכמי האומות העולם.

[3] אוצרות ירושלים חלק יג עמוד ל.

[4] הירץ הומברג (1749-1841) היה איש תנועת ההשכלה מראשית פריחתה בגרמניה.

אך מהראוי להעיר כאן שהקטע שהפסוק שאותו מפרש מהרי"ל ומייחס פירושו למה שראה ב'הכורם', על אותו הפסוק נמצא ב'הכורם' פירוש אחר. שהרי זהו הקטע מתוך ספרו של מהרי"ל דיסקין:

וזה הפירוש שהובא בהכורם על אותו פסוק:

[5] הערה 70.

[6] בנוסף ראוי לשים לב שבהקדמתו ל'אלון בכות' [הספד על הרב דיסקין] מתאר תלמידו הרב יעקב אורנשטיין את גדלותו בתורה של מהרי"ל, ואת בקיאותו העצומה בשני התלמודים, ובדברי הראשונים והאחרונים, ולא כתוב שם ולו ברמז שהיתה לו ידיעה כלשהי בתורת הנסתר. אולם בספר עמוד אש (עמ' ג) כתב שרבי יצחק ירוחם דיסקין ראה בחדר בדידותו המיוחדת של אביו מהרי"ל "את הספרים הגדושים בארגזי הספרים העומדים שם, והנה כולם ספרי קבלה". ואם קבלה היא נקבל.

[7] לדברי יוסף שלמון במאמרו 'איש מלחמה: ר' משה יהושע לייב (מהרי"ל) דיסקין' (ה'גדולים' עמ' 315), ר' יעקב אורנשטיין היה "תלמיד חכם מובהק, שפרסם מאמרים תורניים וכן מאמרים במתמטיקה ופילוסופיה".

[8] יש כאן רמז שמוטב לא לדבר בגודל מעלתו בחכמות חיצוניות.

[9] אלון בכות עמ' 5 והובא ע"י יוסף שלמון במאמרו שבספר ה'גדולים' (עמ' 303).

[10] זכרון יעקב, ג' עמ' 205.

[11] משה ליב ליליינבלום (1843-1910) היה משכיל וסופר מראשי תנועת חובבי ציון ברויסה.

[13] חוקר הלוח העברי ותוכן (1882-1964).

[14] ארשת ה עמ' 387.

[15] המגיד אפריל 4, 1861.

[16] למרות שכעת עתה לא מצאתי דבר זה בעיתון המליץ, ראוי לציין לכתבה אודות העיר שקלאוו שהופיע בהמליץ בשנת 1872 (דצמבר 31) ובו מתלונן הסופר על חסרון השכלה בעיר שקלאוו. בראשית המאמר מעיד הסופר "עדתנו זאת רחוקה עוד מדרך השכלה כמו לפני מאה שנים. כל לימוד וכל סדר חדש, אף שאינו מתנגד במאומה להש"ע ולתורת היהדות פגול המה בעיני העם השוכן בה! רבניה, נגידיה, אלופיה, והמונה. די לשפוט מזה, כי אחרי אשר בחרו לראשונה לרב מטעם הממשלה את ה' פעסקין העבירוה שנתים ימים מכהונתו רק לאשר התנוסס בו רוח השכלה במעט ויאבה לעשות איזה תקונים, לא בדת ודין חילה, רק משטרים נכונים נחוצים למשאלות העת החיה... וגם מנה שטות לא יבל. וזה האות כי בימיו עשו בשנה העברה חופת דודים על שדה הקברים... ואם אמנם הרב התורני הגאון לא עזר לשטות ולא העיר את ההמון לעשות תועבות כאלה, אך גם לא התיצב נגדם לסכל מועדיהם הנבערות, האף כי הוא יודע עד מאד כי היא נגד דת תוה"ק ובידו היה למחות...

[17] הראה לי החכם הרב מהרמ"מ שבקובץ ישורון ח"ו עמ' תשה נזכר פרטים נוספים אודות ביקורו של מהרי"ל דיסקין בעיר פפד"מ.

[18] הלבנון שנה תשיעית, יולי 23, 1873.

[19] בשנת תרנ"

ה הוציא אפרים ראסקין לאור ספר בשם אוצשעבניק-קאנטראליאר אשר מטרתו ללמד כתיבה וקריאה ברוסיה בתוך שלש שבועות בלי צורך למורה.

ראוי להזכיר שבהקדמה לספר '

משפחות ק"

ק שקלאב'

מאת שלמה בערמאן ומיכל רבינוביץ,

ירושלים תרצ"

ו,

נזכר ש"

התורני מו"

ה אפרים ראסקין יליד שקלאב היושב בווארשא,

מו"

ל הלוח ה"

יומי",

אסף הרבה חומר וכתבי יד והתכונן לחבר ולהוציא לאור "

תולדות העיר שקלאב"

כעין הספר "

קריה נאמנה"

לרש"

י פין ז"

ל."

כותב ההקדמה,

שלמה ברמן,

משער בשנת תר"

ץ,

שלא עלה ביד ראסקין לכתוב הספר עפ"

י החומר שאסף מסיבת המלחמה העולמית [

הראשונה].

[20] הלבנון אוגוסט 20, 1873.

[21] מהנכון להעתיק כאן מה'מכתב מהאמלע' שהופיע בהמליץ, בו מתלוצץ משכיל אחד החותם שמו 'יפת"ח הגלעדי מפלך מאהליב' על מנהגי החסידים בעיר האמלע. מענין מאמרינו להעתיק כאן איך שמתאר הסופר הנ"ל מסיבת ליל י"ט כסלו לפני כמעט 150 שנה:

י"ט כסלו הוא ליל שמורים שקימו וקבלו אותו כל המתחסדים לעשותו יום טוב ולכבדהו במשתה שמרים עד בוא הגואל. מי יתן לך קורא יקר כנפי יונה, או מיכאל המלאך יביאך בטיסה אחת לפה וראית את כל ההכנות, השמחה והקדושה והיהודים שמיחדין לשם קוב"ה ושכינתיה בלילה ההוא. כל אחד ואחד מתלבש בבגדי יום טוב ופניו צהובים, כי אין דומה אור פניו של חסיד בכל ימות השנה כקלסתר פניו באותו שעה. לא אכבירה במילים למצוא חשבון כמה בקבוקי יין שרף או כמה אווזות של רבה בר בר חנה ולשונות עם חרדל אשר יהיו לברות למלתעותם. דעת לנבון נקל, כי אז מצוה על כל איש לקחת שקל אחרון מכיס אשתו אשת החיל אשר בזעת אפה תוציאהו, לתתו בקופת הלשכה. הדרושים והשיחות אשר הלמו ומחצו תוף אזני שומעיהם, הלא אבניהם הטבעו לחרף גאוני ומשכילי עמנו, כמו את הרב הגאון ר' יהושע יהודה ליב המכהן פאר בשקלאב, ומשנהו הרה"ג החכם הכולל הכהן הגדול מאחיו מהר"ז ראפאפורט ממינסק – אשר בשם מין וצדוקי יעיזו לכנותו -. ואנכי זכיתי לראות כל המחזה מהחל עד כלה את כל הקהל שמחים וטובי לב – כי בעל האושפיזין שלי הוא מנכבדי בהמ"ד וע"ש נקרא ובביתו יחוגו את החג הנאדר הזה בתופים ובמחולות -, וק"ו בן בנו של ק"ו כי קללת שמעי בן גרא יקללו את האיש הנעלה הרמבמ"ן זצ"ל והחכם ריב"ל ז"ל ואחריהם כל דורשי חכמה ודעת עם כל המוציאים לאור מ"ע לב"י. (המליץ, ספטמבר 5, 1871)

קשה לדעת אם התואר 'משכיל' נופל רק על מהר"ז ראפאפורט ממינסק, והתואר 'גאון' נופל על ראש מהרי"ל דיסקין, ובאמת היה מהרי"ל משולל השכלה, או ששניהם כלולים יחד תחת התואר 'גאוני ומשכילי'. בין כך ובין כך, רואים כאן שנאת החסידים למהרי"ל, ואיך שמשכיל זה קינא לכבודו.

[הרב הגביר הגאון החכם והשלם, ר' יקותיאל זיסל הכהן ראפופורט, מנכבדי עיקר מינסק, היה שר וגדול בתורה ופעל הרבה לטובת הציבור בכלל וישיבת וולוז'ין בפרט (המגיד, מרץ 20, 1872). בשנת 1851 הוציאה הממשלה צו, שילמדו בישיבות את הלשון הרוסית, וראשי הישיבות מצאו דרכים לעקוף את הגזירה הזאת, שכאשר באו פקידים בכירים לבחון את תלמידי הישיבה בידיעת הלשון הרוסית, היו מושיבים לפניהם אלה מן התלמידים שהרוסית היתה ידועה להם מבית אבא. רבי יהושע השיל לעווין, בעל עליות אליהו רצה להכניס אי-אלו תיקונים בישיבת וולוז'ין, כדי שתהיה מוכרת באורח רשמי ע"י הממשלה ותוכל להתחרות בשני בתי-מדרש לרבנים שבווילנה ובזיטומיר. דבר זה היה למורת רוח הרבנים, ולהשקפות גדולי הרבנים הצטרפו הגבאים מווילנא וממינסק, ביניהם בעל תורה וחכמה ועסקנים ציבוריים וותיקים.. מהם כדאי להזכיר את רבי יעקב באריט מווילנא והגביר המפורסם רבי זיסל הכהן רפפורט ממינסק, שאף הם היו בין המכריעים את הכף לטובת הנצי"ב שיעמוד הוא בראש הישיבה ולא הרב לעווין (משה צינוביץ, עץ חיים עמ' 223). מהר"ז הכהן רפפורט נפטר ביום כ"ז אדר א' תרל"ב והספידו הגאון הנצי"ב מוולוז'ין הספד מר (המגיד שם).

בספר 'מקור ברוך' מובא שבעל 'צמח צדק' סיפר לבעל 'ערוך השולחן', שהיה אחד שהתלוצץ על רב נחמן מבראסלאוו נ"ע, אבל הגיב הצמח צדק שאפשר למחול אותו על זה, כי לא ברוח מחלוקת ולא לקנטור וגם לא ברוח שנאה בנפש דיבר מה שדיבר, כי אם לתכלית ההלצה בלבד, וכמו שרגילים לומר במקרה "להשתעשע מטוב לב"; ועם זה, הנה גדול זה האיש בתורה ושלם במדעים ומיוחס גדול, ועל כולם – עשיר ובעל נכסים, אשר כידוע, במצב העשירות יערך בעולם קנינו בתורה ובחכמה פי שנים, ובעיני עצמו – פי חמש; וזה אשר רשם החכם העשיר הזה בגליון אחד הספרים של מהר"ן הנזכר, על מה שכתב מהר"ן "כי בהושענא רבה מצוה לרכוב ולאחוז הושענא ביד"... רשם הנ"ל בגליון בצד הדברים ההם כדברים האלה "היה לו להסמיך זה על הפסוק בתהלים (סח) "לרוכב בערבות"; ושימש כאן בלצון ובהיתול במלה "בערבות" להוראות ערבות מלשון ערבי נחל הושענות, תחת הוראתה האמתית – שמים; "והנה עם כל צדדי הזכות אשר הראיתי לזכותו של האיש הזה – גמר הרב [בעל צמח צדק] את דבריו – עם כל זה אין זה מן הנימוס ודרך ארץ לאנשים מתוקנים ומנומסים". ובהערת שוליים גילה בעל 'מקור ברוך' כי למרות שהרב [צמח צדק] לא קרא בשם את האיש הזה, מבני משפחת הרב נודע לאבי [בעל ערוך השולחן] כי זה מוסב על הרה"ג ר' זיסל רפפורט, ממינסק. (מקור ברוך חלק שלישי, פרק כ סעיף ב)

ראוי לציין כאן מש"כ הרב יהושע מונדשיין ('מקור ברוך'– 'מקור הכזבים') להוכיח מסיפור זה שדברי ה'מקור ברוך' בכזב יסודם. וכך כתב הרב מונדשיין,

ומכיון שה'מקור ברוך' היה לץ מתלוצץ, ורצה להעביר לקוראיו גם דברי חידודין על הצדיקים ועל החסידים, כיצד יעשה זאת? אין לך דבר פשוט מזה: את כל ההלצות הללו נתן בפיו של הצמח צדק שסיפרם באריכות ובפרטי פרטים (בתוספת הסתייגות של צער וכאב על שדברים מגונים מעין אלו נאמרים על הצדיקים...), והכל כשר וישר! כך הצליח ה'מקור ברוך' לשלב בספרו בעקיפין ובצורה "מתוחכמת" דברי לעג וקלס על מרן הבעש"ט נ"ע, על הרה"ק ר' לוי יצחק מברדיטשוב ועל הרה"ק ר' נחמן מברסלב – דבר שלא היה עולה בידו לעשותו אילו רצה לכתוב את אותם הדברים בצורה גלויה וישירה. אגב כך מתאפשר לנו להיווכח בסילוף נוסף של ה'מקור ברוך': הוא מביא בשם הצמח צדק, שמהר"נ מברסלב כותב בספרו "כי בהושענא רבה מצוה לרכוב ולאחוז הושענא ביד, לקיים מה שנאמר מרכבותיך ישועה" (עמ' תרכה), ובכך תולה הוא את דברי הליצנות על הפסוק "לרוכב בערבות". ברם, בכתבי ר"נ מברסלב לא נאמר אלא "מי שרוכב על סוס יוליך עמו הושענות" (ספר המדות, פרק 'דרך' אות ו). וכבר אמרוהו רבותינו הראשונים בקשר לערבה של הושענא רבה: ושמעתי שיש בה סגולת שמירה למתכוין בה בסכנת דרכים (ס' מנורת המאור, נר ג, כלל ד, חלק ו, סוף פרק ז). ואת ה"ליצנות" שה'מקור ברוך' תולה בפסוק "לרוכב בערבות", המעיין בזוהר פ' תרומה (דף קסה, א) יראה שאלו הם דבריו (כמצויין בהגהותיו של הרב מטשעהרין לס' המדות שם).]

[22] בהערת שוליים שבתוך הכתבה מוסיף אפרים ראסקין: אחת מהם אציג לפני הקוראים היקרים: כי שונא בצע הוא, ולבד השכירות אשר נקבה לו עדת שקלאוו, לא יקבל משום איש מתנה אפילו קטנה. וההכנסות אשר נהוגים אצל רב כל עיר בישראל, גם כן לא יקבל. ופזרן גדול הוא בנדבותיו הגדולות לכל דבר טוב ומועיל.

[23] שם.

[24] שם.

[25] בעיתון המגיד (פברואר 3, 1874) מופיע כתבה שבו מתלוצץ הסופר על המנהג שהנהיג מהרי"ל דיסקין בעיר בריסק, שהשמש יחזור על פתחי החנויות להזהירם על השבת. וכך הוא כותב:

בריסק. בצדק תוכל קריתנו לקוות כי השכלה תתחיל לפרוש כנפיה גם במלוא רוחב עירנו הישנה מימי קדם קדמתה, כי מעת אשר נבנו בפה מסלות הברזל מארבע רוחות העיר המתאחדים אותה עם ארבע כנפות הארץ היתה עירנו למרכז גדול לעיר הומים תשואות מלאה ורוכלת עמים ולקול התקיעות והתרועות אשר שומעים אנחנו שלשים קלות בכל שעה וירוצו ויעופו אליה בעל עב קל אנשים רבים מכל המקומות, וכן גרי עירנו יסחרו את הארץ ומסלות הברזל תשאינה אותם לכל ערי העולם. ע"כ תקוה נשקפה כי יעשו חיל בהכירום את אחיהם יושבי הערים אחרות המלאות חכמה ודעת ויראת ד' היא אוצרם. – מי יתן ותבוא שאלתנו ותקותנו בל תהי' מפח נפש.

כן חמד פה לשבת הרב הגאון מו"ה ר' יהושע ליב נ"י מלאמזע אשר היה איתן מושבו עד כה בעיר שקלאב הישנה. על פיו נתחדשו חדשות בהלכות העיר במנהגיה ובעניניה ולדוגמא אציג פה רק חדשה אחת המשמחת את נפש הקורא ומזה ישפוט על השאר. –

הדת מכבוד הדר גאונו יצאה כי מדי ערב שבת בשבתו כחצות היום ילך שמש הקהל בכל רחובות קריה ובחוצותיה מקצה ועד קצה ואל חכו כשופר ישמיע קול רעש גדול אדיר וחזק אשר תצילנה אזני השומע: "זיד פיש" (Sud Fisch)! המנהג הזה ישן נושן הוא ועליו אבד כלה, שאלנו אבותינו ולא הגידו לנו זקנינו ולא אמרו, ועתה אחרי בלותו היתה לו עדנה בעיר מגורתנו.

לב מי לא ישבע עונג ונחת לראות איך יתנו לשמצה יעקב וישראל לגדופים!!! מה נהדר המראה איך שמש הקהל החרד אל דברי משלחו יצעד כגבור משכיל בחוצות העיר ישתקשק ברחבותיה בגאון ובשלות השקט ושואג בקול את הפזמון שלו החודר מאוד לאזני השומע כסוד שיח שרפי קודש! וכאשר יפגשוהו אנשים אשר לא מבני ישראל ימלאו שחוק פיהם ולשונם קלסה ואחריו ראש יגיעו בהבינם לדעת איך רוח הזמן (!) נשפכה על יושבי עירנו ומרחפת על פני שערינו וחוצותינו! אשרי עין תראה כל אלה ולמשמע אוזן דאבה נפשנו!

עוד יזעקו המשכילים ואוהבי עמם באמת מרה בשערי מכתבי עתים על הרבנים הרועים את צאן יעקב כי מודדי אור המה ויושבים אחורי התנור והכירים מבלי עשות תושיה להועיל לטובת הכלל ואין חולה מהם עלינו! תואנה המה מבקשים! יראו לדעת כי שקר יענה פיהם, יראו לדעת כי לא אלמן ישראל מרעפארמאטארען וממתחדשים חדשות לבקרים לכבוד ישראל לעמן יאמרו בעמים רק עם חכם ונבון וכו'! יראו אחינו ורבנינו בהערים הגדולות ויעשו גם המה כמעשה אחיהם הגאון בעירנו בתקונו הגדול לתפארת ישראל ולתועלתו! א. ל פ"ז.

[26] ראה שבת (לה, ב) "כדי לצלות דג קטן".

[27] הלבנון מרץ 11, 1874.

[28] בתוך החומות עמ' 200. תודה רבה לידידי הרב משה מיימון שהפנה אותי למקור זה.

[29] שם.

[30] שם עמ' 202.

[31] שם עמ' 203.

[32] שם.

[33] יוסף שלמון במאמרו 'איש מלחמה: ר' משה יהושע לייב (מהרי"ל) דיסקין' שהופיע בספר ה'גדולים' (עמ' 315), למרות שהוא לא דן ברוב המקורות שהבאנו בקשר להשכלתו הכללית של מהרי"ל, הוא מסכם את הדברים בנוסח הזה:

יעקב אורנשטיין, כמו הרב דיסקין ואפילו הרבנית דיסקין, היו תוצר של תופעה מנטלית של היפוך התודעה: הם – שהיו בקיאים בחכמות חיצוניות והכירו את העולם מחוץ למובלעת של קהילתם הירושלמית או המזרח-אירופאית – הפכו לשוללי ההשכלה הכללית, המודרנה, המערב, והעולם מחוץ ל'מובלעת', שבהם תלו את חילון. הייתה זו שלילה אידיאולוגית ולא נטיית לב המבוססת על זרות או ניכור.

[34] נולד ביום כ"ט אלול תקמ"ח (1788) ונפטר ביום כ"ב שבט תר"כ (1860).

[35] מר דרור – ניו יארק 1929 מתורגם מספרו "די וועלט דערציילט" ניו יורק כרך שני תרפ"ט עמוד 136. מיד לפני פירסם מאמרי' ראיתי בספר 'נאחז בסבך' מדוד אסף עמ' 43 הע' 49 שמתייחס לסיפור זה כ'פולקלור משכילי'. ועתה ראיתי ב'לשם שמים' מאת עמנואל אטקס (עמ' 282 הע' 36) שסיפור זה מובא ע"י ריב"ל בעצמו במהדורה שנייה של הספר תעודה בישראל (ווילנא תרט"ז) ב'ראש דבר למהדורא תניינא' בהערת שוליים על המילים "וגאוני הזמן במדינה זו וחוצה לה נתנו עליו עטרת תפארת, וירוממוהו בקהל עם ברשיונם" וכך כתב:

והגאון האמיתי ר' אבלי הראב"ד דווילנא נ"ע, אחרי תתו הסכמתו עליו, שאלוהו נכבדי קהלת ווילנא באסיפה רבה לאמור: מה ספר זה? מה טובו? ומה חסרונו? ויען הרב קבל-עם "לא נמצא בו חסרון כי אם זה: שלא חיברו רבינו הגדול ר' אליהו החסיד דווילנא".

[36] 'שטעט און שטעטלעך אין אוקראינע' כרך שני ערך "יצחק בער לעווינזאן" עמוד 49.

[37] ראה מש"כ אריה מורגנשטרן ב'גאולה בדרך הטבע' הוצאת 'מאור תשנ"ז; עמוד 163 הערה 26 אודות הסכמה זו.

[38] הגאון ח"ג עמוד 1305.

[39] שם הערה 18.

[40] מיד לפני פירסם מאמרי זה, ראיתי בספר 'נאחז בסבך' מדוד אסף (עמ' 43 הע' 49) שהוכיח מלשון זה 'אחורי התנור בבית המדרש', "שיצקן, עורך היומון 'היינט', הביא זאת כדבר הבל שסופר 'אחורי התנור בבית המדרש'. אינני משוכנע שזוהי כוונת יצקן, וגם לא נראה כן מהקשרם של הדברים, שהרי יצקן משתמש בזה להוכיח שרבי זלמלי לא היה מעניק הסכמה לרש"ד אילו הכירו טוב. בין השאר כותב יצקן "עוד לא הגיע בימים ההם לליטא רוח ברלין, וגדולי וילנא לא ידעו מאומה מכל הנעשה בין אחיהם הרחוקים אשר באשכנז. ספק גדול הוא בעינינו אם היה רבי זלמלי מולאזין נותן הסכמתו על ספרי רש"ד... לו ידע באמת מי הוא זה הרש"ד, כי היה חבר להרמבמ"ן, ומי הוא הרמבמ"ן ומה שמרננים אחריו. לא נוכל להחליט כי היה מתנגד [רבי זלמלי] להם כיתר הרבנים הקנאים בדורו, מאחר שאין אנו יודעים מדת רוחו בדברים כאלה, אבל גם הסכמה, כמדומה שלא היה נותן". מיד אחר דברים האלה מביא יצקן 'ראיה' לדבריו מהסיפורים אודות רבי אבלי, ומסיק "מכל אלה יכולים אנחנו לראות כבראי את מחזה התמימות והאדיקות הנוראה, שהיו אבותינו שקועים בה בראשם ורובם, מבלי לזוז ממנה אף כמלא נימא, בהיות נפשם ורוחם מסורים לדתם ולתורתם ויפחדו מפני כל צל עובר ועוף פורח לבל ידע חלילה לרעה באישן בת עינם. וגם אין כל פלא ושמץ טינא על רבי זלמלי הצדיק אם לא היה נותן הסכמתו על ספרו של רש"ד הבא מברלין, לו רק ידע מאיזה חברה הוא בא ואת כל הנעשה שם. ואם נתן, קרוב לודאי, כי לא ידע מאומה, ולא היה לפניו רק מה שעיניו רואות". כלומר, שלדעת יצחק לא היו אדוקים כמו רבי זלמלי ורבי אבלי מעניקים הסכמה לספרי משכילים אילו ידעו שיש בהם שמץ של השכלה ובאים לחלל את הקודש.

[41] ש"י יצקן, ורשה תר"ס עמ' 119. מעניין שהסופר 'בנימין נהוראי', במוסף שבת קודש של יתד נאמן; תשנ"א פרשת שמות העתיק כמעט כל דברי יצקן, אבל השמיט השורה "ויתמרמר הזקן ובחמת רוחו הכהו על הלחי לאות ולחרפה על שאלתו הנבערה". אולי לא רצה נהוראי שילמדו קוראי היתד מדרכי המו"ץ של ווילנא ויעשו כמעשהו.

[42] ראה הערה למעלה אודות הסכמה זו.

[43] 'הגאון' חלק ב עמודים 633-634.

[44] לשונו של ריב"ל בריש התעודה בישראל.