Some Highlights of the Upcoming Taj Art Auction*

With the proliferation of auction houses and the centralized platform of Bidspirit, there are auctions of Judaica and Hebraica on a weekly, if not more frequent, basis. One of the more recent entrants into this arena is Taj Art, founded in 2021 by Tomer Rosenfeld and Aron Orzel. This Sunday, December 24th, at 7 pm Israel time, Taj Art will be hosting their 11th auction, which includes some items of particular bibliographical and historical note.

The full catalog is available here, and a pdf of the highlights brochure is here.

The first (lot 9) is a work that appears in a story that is a touchstone for the modern feminist agenda.

According to R. Barkuh HaLevi Epstein, he maintained a regular dialogue with Netziv’s first wife, Rayna Batya. Among the topics of conversation was the issue of women studying Jewish literature. Rayna was well-versed and regularly studied an impressive array of Jewish books.

Epstein, in his Mekor Barukh, attempts to place Rayna as less of an anomaly but more as one within a chain, albeit small of women throughout Jewish history that similarly shared Rayna’s interest and erudition of Jewish texts. While there is little doubt that there are examples of such women, many of Epstein’s examples are corrupt at best and deliberate misreading of the sources at worst. Nonetheless, there is little doubt that Rayna was an erudite woman. According to Epstein, Rayna eventually won him over to her position when she identified a responsa that provided that women could study traditional texts. The source was Ma’ayan Ganim. Epstein repeats the position of Ma’ayan Ganim in his commentary on the Torah, Torah Temimah (although without reference to Rayna or a particular episode).

First, we should note that Marc Shapiro has questioned the veracity of the entire story in his article on this site, which is subject to a rebuttal by Y. Lander. Eliyana Adler’s article, “Reading Rayna Batya: The Rebellious Rebbitzen as Self-Reflection,” (available here), collects additional discussions regarding the event and provides her approach to the story. While one can debate the merit and implications for Jewish feminism, it is worth briefly discussing the obscure work Ma’ayan Ganim.

The Ma’ayan Ganim, authored by the Italian rabbi Shmuel Archovalti, was published in 1553 in a small format and consisted of 50 letters intended to guide effective communication. Unlike many other legal systems, Jewish law largely relies on responsa, letters from rabbis in response to queries (although, in some instances, contrived rather than actual). Despite the format, not all letters are legal, and certainly, a text with sample letters intending to serve as a writing tool does not qualify as legally binding. Irrespective of the purpose, the letters demonstrate an interest in the issue that held the interest of many rabbis and others. Similarly, whether or not Epstein created the entire episode or embellished parts of it does not detract from his position that encouraged women’s study of Jewish texts.

While Rayna Batya has enjoyed questionable notoriety, it is disappointing that a woman whose advocacy for women’s study and Jewish women’s rights was well documented and received the respect of leading Jewish rabbis and scholars is today nearly forgotten. Ironically, as Dr. Leiman highlights, the New Jewish Encyclopedia notes that prior Encyclopedias Jewish women were marginalized, it too fails to record Esther. The one exception to this forgetfulness is the Encyclopedia for the Zionist Leaders, which records Esther and some of her accomplishments. Today, however, there is a very robust discussion of many of Esther’s unique contributions and essential ideas that appeared here: https://mizrachi.org/hamizrachi/the-time-of-our-freedom/

It includes translating one of Esther’s articles that appeared in the Jewish press.

Two books are written by R. Yitzhak Chaim Kohen MeChazanim (Cantarini), Et Kets and Pachad Yitzhak (Lot 22). The former was published in 1710 and the latter in 1685. Despite the gap in time, both contain a fully illustrated page that precedes the title page and depicts the Akadeh. Et Kets discusses the messianic era, while Pachad Yitzhak is devoted to discussing the Jews of Padua, avoiding being massacred by an angry mob. Despite the same iconography, the two illustrations were likely done by two different artists and contain subtle but important differences.

The overall depictions are of two different time periods of the Akedah episode. In the first, the illustrations depict Abraham just as he was about to slaughter Isaac and the angel calling to stop him. But, in the second, the illustration is of Abraham going after the ram, not Isaac. The significance of this is tied to the actual books. In Pachad Yitzhak, the book discusses a terrific threat to the Jews and their salvation. Thus, the illustration is similar – the terrific threat to Isaac and salvation. The second work, Et Kets, is a much more positive book. This work has no fear of the prior; instead, it is fully devoted to the Messiah, and thus, the illustration is only of the ram and its sacrifice. Lot 22 is Pachad Yitzhak, the rarer of the two.

Further, different Hebrew words appear in both illustrations. On the first, the word ערכה (prepared or set up) appears across Abraham’s chest. This word expresses Abraham’s readiness to sacrifice Isaac. It would seem, similarly, that the Jews of Padua were willing to sacrifice themselves for God. But the word ערכה only means to prepare and not actually to sacrifice. Thus, Isaac was only prepared but not sacrificed, and so too, the Jews of Padua were placed in danger but ultimately redeemed.

In Et Kets, the words ירא יראה appear. These words reference what Abraham called the place where the Akedah took place. Importantly, Abraham uttered these words after the entire episode. These were words of jubilation on his passing his test and Isaac’s redemption. Again, these words fit well with the content of Et Kets.

These allusions are unsurprising, considering the style of R. Dr. Cantarini. His books are written rather cryptically, with many allusions to Biblical and other themes throughout. (See our fuller discussion here.)

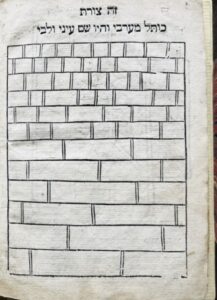

Many Hebrew books include a depiction of the Temple Mount, represented by the Dome of the Rock. However, Lot 43, Zikrohn Yerushalim, published in 1742, consists of a depiction of the Dome of the Rock (surrounded by a Medieval wall and town) but broke new ground in depicting the Kotel to represent the Jewish Temple. This is the first time the Kotel ever appeared in a Jewish book. Yet, only in the 19th century did the Jewish books fully transition to the Kotel rather than the Dome of the Rock.

There are two notable works by R. Emden, his Siddur, (lot 52), and R. Azreil Hildeshiemer’s copy of Meor u-Ketziah (lot 175). This edition of the Siddur is especially important as most of the reprints (until recently) only included the commentary, and the actual text of the Siddur did not reflect many of R. Emden’s approaches and, frequently, a direct conflict between the commentary and the text.

There are two notable works by R. Emden, his Siddur, (lot 52), and R. Azreil Hildeshiemer’s copy of Meor u-Ketziah (lot 175). This edition of the Siddur is especially important as most of the reprints (until recently) only included the commentary, and the actual text of the Siddur did not reflect many of R. Emden’s approaches and, frequently, a direct conflict between the commentary and the text.

There are some very rare antiquarian books, an incunabulum from Radak, (lot 149), published in 1486 by Soncino. Lot 148 is a leaf from a manuscript of Rambam’s commentary of the Mishna dated to 1222 and transcribed in Yemen. One of the rarest Bomberg volumes of the Talmud is Mesechet Avodah Zarah, lot 32. Of course, because this tractate discusses non-Jews and their relationship to Jews, it was particularly fraught. Indeed, after the resumption of the printing of the Talmud in Basel after the ban in the early 16th century, it omitted this tractate entirely. (There are also two other Bomberg volumes, lots 33–34).

Eliyahu HaBakhur (Elia Levita) wrote one of the earliest grammar and dictionaries of Hebrew and Aramaic in the modern period. Lot 86, is the first edition of his Sefer HaBakhur, Isny, 1541. A more recent reprint was subject to censorship due to including a particular commentary. See our discussion, “A New Book Censored.”

There are also a few books that contain noteworthy illustrations. Lot 87 is Tzurat ha-Arets, Basel, 1546, which includes astronomical images. Lot 89, is an edition of the fundamental kabbalistic work, Razeil ha-Malakh, that depicts the star of David and kabbalistic amulets.

The issue of rabbinic pay appears to have affected even the greatest of rabbis. Lot 205 is a letter from R. Chaim Ozer to the Vilna community pleading for a raise because he is so destitute that “he will not have money for rent or food.”

In all, there are a number of highly collectible items, and the catalog is certainly worth a closer look.

*This is part our series on upcoming auctions, “Auction Highlights.” These provide the opportunity to revisit previous posts and provide short notes about books and other related items.