A Tribute to Rav Shlomo Elyashiv,

Author of Leshem Shevo v-Achloma:

On his Ninetieth Yahrzeit

by Joey Rosenfeld

Joey Rosenfeld is a psychotherapist in St. Louis where he moved with his family. He published his first sefer, sc’hok d’yitzchak on the Kabbalistic theme butzina d’kardinusa, or darkened light. He is currently working on a monograph of R. Shlomo Elyashiv and the philosophical and psychoanalytic themes in Leshem Shevo v-Achloma.

His first essay at the Seforim blog, is entitled: “Dorshei Yichudcha: A Portrait of Professor Elliot R. Wolfson,” is available here.

A torch of holy fire, speaker of heights

Sent from on-high to reveal the concealed

Enlightened the darkness through Leshem Shevo v-Achlomot

The Rav like an Angel of God

Genius of the world signified and clear

Secrets of the world in the Torah of truth

Revealed and opened before him

Righteous pillar of the world, vessel of modesty

A great humility in his roots

Our great teacher supernal holiness

Master of secrets unique in his generation

Our teacher R. Shlomo Elyashiv zt"l nbg"m

Author of the holy books Ha"Kadosh v-Leshem Shevo v-Achloma

Called to the Heavenly academy

27th of Adar 1925 here in the holy city of Jerusalem

May his soul be engraved in eternal life

and may his merit protect us Amen

--Rav Avraham Yitzhak Ha-Kohen Kook’s handwritten epitaph for Rav Shlomo Elyashiv, which is made available here courtesy of the private collection of Reb Shlomo Gross.

Lurianic Mysticism

When R. Issac Luria (1534-1572) known as the Arizal, developed his theosophical system often referred to as Kabbalat Ha-Ari or Lurianic Mysticism, he initiated a revolution within the Jewish mystical tradition.[1] In the margins of his predecessor and teacher R. Moshe Cordevaro (1522-1570) and through a highly innovative form of Zoharic hermeneutics, the Arizal established a radical approach to the ancient theories of Jewish cosmology (tzimtzum, shevirat ha-keilim), theurgy (kaavanot) and eschatology (tikkun). Codified by his various disciples, primarily R. Chaim Vital (1542-1620) and R. Yisrael Sarug (1590-1610), the Lurianic system took form in the work Eitz-Chaim and the eight volumes of collected teachings known as Shemoneh-Shearim.[2]After the Arizal’s passing, it was generally agreed upon that the Lurianic corpus should, and would remain a closed system, one in which novelty and creativity from subsequent scholars was discouraged and even prohibited. The treatment of the Lurianic corpus as a sacred textual matrix in which creative hermeneutics are discouraged appears to stem from epistemological as well as philological phenomenon. On the epistemological register, the esoteric material being elucidated within the Lurianic system was viewed as an exceedingly sensitive body-of-work that demanded a high level of secrecy and concealment.[3] Only the most spiritually refined individuals were seen as worthy and capable of processing the complexities of the kabbalah. While the political secrecy surrounding the Arizal and his disciples was not a new phenomenon in the history of Jewish esotericism; the emphasis placed on character refinement, both spiritual and physical, for the sake of initiation into the ranks of talmidei ha-Ari is noteworthy. The danger of an unqualified and inexperienced student imposing his own imaginative interpretations upon the system was seen as a potentially catastrophic event with both spiritual and historical consequences.[4] On the philological register, the Arizal himself imposed strict prohibitions upon his disciples regarding the sharing or revelation of his insights, thus creating an economy of occlusion in which his ideas flourished within the strict contours of secrecy. Historically, the Arizal’s pedagogical methods perpetuated the veil of secrecy that kept his teachings hidden while simultaneously enabling them to be collected. Much like the rabbinic sages of the Talmud, R. Issac Luria maintained a strict orality while teaching his disciples. Continuing the rabbinic model wherein oral teachings are associated with a direct teacher-student relationship in which the risk of mistakes and misunderstanding is mitigated, the Arizal delivered his teachings in small groups, often prohibiting his students from textually recording his lessons. It wasn’t until the Arizal was near death that he allowed his disciple R. Chaim Vital to exclusively record his teachings posthumously.

Interpretations of the Lurianic system

While various attempts at interpreting the Lurianic system following R. Issac Luria’s passing did exist, it wasn’t until the seventeenth-century that authoritative schools of interpretation were born. Generally speaking one may categorize four primary approaches towards Kabbalat Ha-Ari in which the Lurianic system was expounded while simultaneously adhering to the strict prohibition of creating concepts that had not been directly recorded by R. Chaim Vital. While each school contained followers who differed from the founding member, the four major personalities associated with unfolding the Arizal’s system were R. Moshe Chaim Luzzatto (1707-1746) known as the Ramchal, R. Elijah of Vilna, known as the Gaon of Vilna (1720-1797), R. Shalom Sharabi (1720-1777) known as the Rashash, and R. Yisrael ben Eliezer (1700-1760), known as the Baal Shem Tov. Respectively, each school can be said to have utilized a different mode of hermeneutical interpretation in emphasizing what they viewed as the fundamental aspect of Lurianic Kabbalah, or Kabbalat Ha-Ari. For Ramchal and his Padua school[5] an emphasis was placed on unpacking the metaphorical nature of the Lurianic system for the purpose of revealing the various modes (hanhaagot) in which the Divine is manifest throughout history, culminating with the metahistorical eschaton in which all will be rectified (tikkun) and unified (yichud). For Rashash and the Jerusalem kabbalists of the Beit El Yeshiva[6] the emphasis was placed almost exclusively on the theurgical nature of religious phenomenology, expounding and developing a highly complex and intricate system of mystical intentions (kavaanot) associated with prayer and religious ritual. The Baal Shem Tov,[7] founder of the Hasidic movement along with his early students read and translated the intricate details of Kabbalat Ha-Ari unto the psychological register, transferring the locus of the Arizal’s system from the hidden depths of the Godhead to the hidden depths of the individual soul, thereby democratizing the once guarded secrets of concealed wisdom (chochmat ha-nistar). The School known as Kabbalat Ha-Gra or Lithuanian Kabbalah,[8] consisting of the Vilna Gaon and the select disciples who learnt directly or indirectly from him, emphasized the spiritual nature of temporality and history with a focus on the Messianic personalities who actively participate in the apocalyptic eschaton, as well as the biblical allusions towards the Lurianic system.

Fourfold of Kabbalistic PaRDeS

It has been suggested that these four schools of Kabbalistic interpretation be compartmentalized according to the fourfold structure of rabbinic hermeneutics known as PaRDeS[9]- an acronym for Peshat, the literal meaning; Remez, the allegorical meaning; Drash, the moral meaning; and Sod, the secret meaning. Generally speaking the gamut of Jewish esotericism-including Kabbalat Ha-Ari- represents the realm of Sod, and as such these four schools of thought would represent the specific substructure of PaRDeS as applied to the Sod of the general structure of PaRDeS. The Rashash and his school primarily engage the textual edifice of Kabbalat Ha-Ari, unearthing apparent contradictions within the system itself while reconciling them through an innovative theory of relativity (erchin) represent the literal approach (Peshat) to the Arizal’s system. The Gra and his school exemplify the allegorical approach (Remez) by utilizing the various forms of creative hermeneutics- primarily sacred numerology (Gematria) and acronyms (Roshei Tevot)- to uncover allusions and intimations signifying aspects of the Lurianic system within biblical texts. The attempt of the Ramchal and his school to uncover the latent meaning within the metaphors of the Arizal represents the moral approach (Drash) in which the externalities of the system are plumbed and simultaneously shed to reveal the inner kernel of meaning. Finally, the Baal Shem Tov and the Hasidic approach, by translating Lurianic ontology into psychological terms represent the essential secret (Sod) wherein the spiritual seeker finds the entirety of existence within themselves thus enabling a unique form of dynamic divine service.

R. Shlomo Elyashiv: Leshem Shevo v-Achloma

R. Shlomo Elyashiv (1841-1926) known as the Leshem after his vast body-of-work Leshem Shevo v-Achloma was a Lithuanian Kabbalist known for his adherence to the school of Kabbalat Ha-Gra.[10] Described as the fourth stage, or peh revieeh within the chain of talmidei ha-Gra, the Leshem formed a system in which the apparent contradictions between the Vilna Gaon and the Arizal were reconciled through a unique form of Kabbalistic analytics. R. Avraham Yitzhak ha-Kohen Kook, close friend and student of the Leshem described R. Elyashiv as applying Talmudic analytics (pilpul) onto the Lurianic corpus thereby clarifying and reconciling the various contradictions and textual ambiguities.[11] With an exhaustive knowledge of the gamut of Jewish esoterica- from the philosophic rationality of the rishonim to the complex intricacies of R. Chaim de La Rosa’s Torat Chachom[12]- the Leshem can be described as one of the most comprehensive as well as creative Kabbalistic thinkers of the late 19th and early 20th century. Born in Zagory, a small city in northern Lithuania, R. Elyashiv was raised studying Talmud with his father R. Chaim Chaikl Elyashiv until leaving home to study under the tutelage of R. Gershon Tanchum of Minsk where he became known for his Talmudic expertise. After his marriage to the daughter of R. Dovid Fein the Leshem went on to study at the Telshe yeshiva where his intellect and vast memory earned him the appellation of Telsher illui. While in Telshe the Leshem was introduced to chochmat ha-nistar by his teacher R. Yosef Reissen who then served as the Rav of Telshe. While learning in Telshe, R. Elyashiv became familiar with the fundamental texts of Jewish mysticism, learning the Pardes Rimonim of R. Moshe Cordevero as well as the Vilna Gaon’s commentaries on Sefer Yetzirah, Safra D’Tzniyuta and the Tikkunei Zohar. Only afterwards did the Leshem begin studying the system of the Arizal and it’s commentaries. R. Aryeh Levin who served as R. Elyashiv’s assistant after the latter’s move to Jerusalem includes within the curriculum the texts of R. Moshe Chaim Luzzato as well; however the distinctive relationship between R. Shlomo Elyashiv and the Ramchal’s school of Lurianic mysticism will be discussed below. After leaving Telshe, the Leshem settled in Shavel, Lithuania where he began to write what would become his vast oeuvre known as Leshem Shevo v-Achloma. In 1922, through the help of Rav Avraham Isaac haKohen Kook and Rav Yitzhak haLevi Herzog,[13] R. Shlomo Elyashiv moved to Jerusalem with his family where he eventually passed away on the 27th of Adar in 1926. While never accepting upon himself any form of communal leadership, the Leshem became known as the preeminent scholar of Kabbalah, through his written works, glosses, vast reaching editorial skills and the various rabbinic personalities with whom he studied and taught.[14]

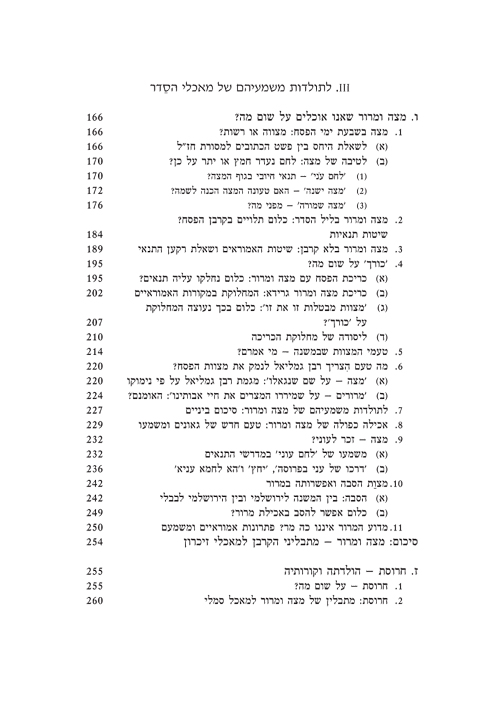

Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Overview of Texts

R. Elyashiv’s oeuvre generally referred to as Leshem Shevo v-Achloma is comprised of four separate yet highly integrated volumes.[15] While a comprehensive overview of each work is far beyond the scope of this essay, what follows is an attempt to describe the framework and context of each sefer. The four Kabbalistic works are Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Hakdamot u-Shearim (1909); Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Drushei Olam ha-Tohu (1911); Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Klalei Hitpashtut v-Histalkut (1924); and Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Chelek ha-Biurim (1935).

Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Hakdamot u-Shearim

Known as Sefer Hakdo”Sh,[16] this work serves as an introduction to Kabbalat ha-Ari for the novice student, clarifying such concepts as Divine names, unity of God and the mystical anthropomorphization of God. In an attempt to simplify the complexities of Lurianic Kabbalah, R. Elyashiv sets forth a five staged multileveled process through which Ein Sof becomes manifest in/as reality. There is nothing particularly original in the Leshem’s depiction of a five stage process, an idea that is ever-present in the Lurianic system of partzufim. The novelty of Sefer Hakadosh, however, may be found in the Leshem’s configuration wherein the five partzufim; Arich Anpin, Abba, Immah, Zeir Anpin and Malchut are analogously aligned with the five-tiered revelatory process (seder ha-gilluim) in which the latent potentiality of existence emerges as the manifest actuality of creation. These stages, or orders-of-revelation are Ein Sof; Tzimtzum/Kav; Adam Kadmon; Atzilut; and the triadic unit Beriah,Yetziraand Asiya (BY”A). Working with certain Lurianic axioms as refracted through Rashash’s concept of hitklalut v-hitkashrut (integration and redistribution),[17] R. Elyashiv depicts a highly integrated system in which each general stage (seder klali) encompasses a subsystem (seder prati) wherein the five stages operate in a self-contained manner. Thus for example, the general partzufof Abba- analogous to the revelatory stage of Adam Kadmon- contains within itself a subsystem comprised of every other partzuf and/or gillui. Far from a theoretical divergence into complexities, this multivalent system wherein each part contains the whole rests at the foundation of the Leshem’s system of integration (seder ha-klilut) and secret of unity (sod ha-achdut). The first seven gates of Hakadoshdiscuss each revelatory-stage in detail including the interconnection between each stage, thus engaging the reader in a textual excursion through the basic framework of the Lurianic system. The eighth gate in Hakadosh- titled Shaar ha-Poneh Kadim- comprises a work unto its own. Here R. Elyashiv undertakes the formidable task of elucidating the Kabbalistic system of R. Yisrael Sarug, commonly referred to as Olam ha-Malbush.While an overview of Olam ha-Malbushas refracted through the works of R. Naftali Hertz Bacharach and R. Menachem Azariah of Fano is far beyond the scope of this essay, R. Elyashiv’s decision toinclude R. Sarug’s depiction of “hidden mysteries that begin far beyond the worlds described in the writings of our master R. Chaim Vital,” is a significant gesture regarding the source and validity of the Sarugian system.[18]

Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Drushei Olam ha-Tohu

Drushei Olam ha-Tohu - or Deah as it is known - is a monumental work that deals primarily with the Lurianic cosmological theme Olam ha-Tohu, the world(s) of chaos. Comprised of two parts, Sefer haDeahexamines the primordial cataclysm known as the shattering of the vessels (shevirat ha-keilim). For the Leshem, this event- known as the death of the Edomite kings (mitat malchei edom) after the biblical account in parshat VaYishlach- serves as the pre-original opening through which the entirety of history unfolds. Far beyond a simple depiction, or elucidation of this Lurianic motif, part one discusses the “roots and foundations, existence and kingship, death and shattering” of the primordial kings, as well as “the ramifications that are born through this process, the source and the purpose of all this and the general process of rectification.”[19] According to R. Elyashiv the shevira was not an isolated event whose effects were limited to immediate consequences, rather, it serves as the traumatic source of everything that follows.[20] The stage of tohu- and all that transpires therein- is the constitutive break through which history gains its subjectivity. On a psychoanalytic register, not unlike Freud’s original seduction theory, the shattering of the vessels and the subsequent chaos represents the original trauma whose symptoms constitute the subject, as opposed to preexistent subject who experiences the symptoms. The worlds of tohu, resting at the beginning- before the beginning- accompany the historical process, concealed from sight, imposing and composing the ebb and flow of shevira and tikkun, shattering and rectification, which make up history.[21] Part one examines the roots of the necessarily imperfect tohu, from its most concealed source to its revealed manifestation as the existential condition of this-worldliness (olam ha-zeh or asiyah). Part two of Sefer haDeah, while similar to part one in that it deals with the various states of pre and post-shattered existence, is unique in both its conceptual arrangement as well as its area of focus. In part one the Leshemutilizes the complexities of the Lurianic system as well as the textual contradictions therein to slowly build his system. The second chelek assumes that the reader has a knowledge of these complex details and moves beyond the pratim to engage the biblical and historical manifestations of the framework described in the first chelek.R. Elyashiv sees the basic structure of shevira-tikkun, or chaos-order as a pattern that incessantly reasserts itself unto the stage of history. Moving from Adam ha-Rishon’s prelapsarian state, through the primordial serpent’s seduction, the Leshem illuminates the subterranean flow of Divine interpolation which he calls nora ahlilah based on the verse in Psalms (66:5), “Lichu u-riuh mif’alot Elokim nora ahlilah al bnei adam.” R. Elyashiv moves from Adam ha-Rishon’s expulsion from Eden to the narratives of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, interweaving Lurianic interpretations with his distinctive focus on the delicate balance between the forces of tohu and tikkun. From there the Leshem goes on to describe the concealed essence of Knesset Yisrael’s movement from Egyptian servitude, the exilic wanderings in the wilderness, and the eventual climactic experience at Har Sinai. The Leshem continues clearing a path from Israel’s unconscious repetition of the shevira as embodied in the collective event of Cheit ha-Eigel towards the eschatological advent as depicted in the Rabbinic feasts of the righteous wherein the enigmatic Leviathan, Behemoth and Ziz Shadi take on immense Kabbalistic significance. The second chelek also includes an extensive treatment of the Talmudic narrative of the four who entered the Pardes as well as an analysis of R. Akiva and his nonlocal relationship with Moses. The Leshem closes Sefer haDeah with various maamarim that while related to the concepts expressed in Dea”hcomprise a separate unit; these include Drush Eitz ha-Daat; Drush Sfeikot Iggulim vi-Yosher; and Drush Mi’ut ha-Yareiach.

Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Klalei Hitpashtut v-Histalkut

Klalei Hitpashtut v-Histalkut- or Sefer HaKlalim as it is referred to- can be described as R. Elyashiv’s most difficult as well as significant work. Following the Arizal’s depiction of the dialectical process through which existence comes-to-be as described in EitzChaim- particularly Shaar Mati v-lo Mati and Shaar ha-Akudim- the Leshem builds a system wherein each stage of revelation contains within itself a subsystem of Hitpashtut, egression and Histalkut,regression. In laying out the framework of this work, R. Elyashiv describes a comprehensive system “In which we will speak regarding the weaving and concatenation of the worlds. From the heights of the most elevated world to the limit of the lower worlds, Briah, Yetziraand Asiyah.”[22] For the Leshem the constant ebb and flow in which existence is revealed in order to be concealed as it is concealed in order to be revealed marks the basic structural framework that enlivens reality.[23] The dialectical play of egression/revelation and regression/concealment that serves to produce each subsequent stage of existence opens into the fourfold process of Hitpashtut Alef; Histalkut Alef; Hitpashtut Beit; Histalkut Beit. Generally speaking, through the act of Hitpashtut, the prior plenitude- seen as infinite relative to the ensuing stage- undergoes a process of concealment, akin to the first Tzimtzumin that, paradoxically, the prior levels concealment allows the next level to transition from its covert potential within the previous level into the overt manifestation as the new stage in existence. Next, with the first Histalkut, the new level now revealed undergoes a process of regression where what has become manifest returns to its previous source, leaving behind a roshem, or trace thus engraving a potential space in which the new level will eventually concretize. While an overview of this complex dynamic is far beyond the scope of this essay the main goal for the Leshem is to show how each and every stage can trace “their roots and spacing within the world of Adam Kadmon, both the details and the details of the details. To show how they are all eternally rooted and unified there, from the initial thought until the limit of action.”[24] In emphasizing the significance of this system, there is no better description than the words of R. Elyashiv himself, printed on the title page of the sefer:

“And the concept of the two Hitpashtiut and the two Histalkiut is as follows, for the Creator blessed be His Name has established the entirety of existence- the totality of which stems only from the surge of His blessed light that is revealed through His actions and his hanhagot from eternity to eternity- He has established it upon the concatenation of many stages, one below the other; and each stage is a totalized system and the entirety of a world, and that which is in this one is in that one as well, with each subsequent stage drawing from the preceding stage situated above it; and now each world has its source above it from which it is drawn and in/through which it exists; and upon this rests the two Hitpashtiut and the two Histalkiut, for the first Hitpashtut and Histalkut form the supernal source of each world that remains above, and the second Hitpashtut and Histalkut form the essential existence of each world in its physical space below. And now, these stem from the light of the Name Yud-Hei-Vav-Hei that shines in each and every world. The first Hitpashtutand Histalkut stem from the letters Yud-Hei of the Name, and the second Hitpashtut and Histalkut stem from the letters Vav-Hei of the Name.”[25]

Sefer Ha-Klalim is made up of two parts discussing each stage of existence and the fourfold process of Hitpashtut and Histalkut that occurs therein. The second chelek is primarily comprised of perek eighteen, anaf ten, or Chai Ani (Yud-Cheit, Anaf-Yud) which the Leshem describes as “the sum total of all of my teachings to show the interconnection of everything within A”K and A”K within everything.” Due to the highly complex nature of this system- running from the unconscious depths of the concealed Godhead to the existential reality of this-worldliness- the Leshem appended a chart in which the system of 52 integrated manifestations of the Tetragrammaton are codified and elucidated.

Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Chelek ha-Biurim

In Chelek ha-Biurim R. Elyashiv undertakes the enormous task of writing a “wondrous and detailed elucidation of the entirety of the Holiest of Holy, the Arizal’s Eitz Chaim.” While numerous works have been written on Sefer Eitz Chaim, simplifying and clarifying the Lurianic system, the Leshem’s vision lay beyond the normative approach to the text. For the Leshem, R. Chaim Vital’s Eitz Chaim represents a work whose “words are blocked and closed off, concealed by ancient days, as R. Chaim Vital wrote in his introduction, that all that has been revealed to us is nothing but the revelation of a singular handbreadth through the concealment of thousands.” As such, a worthy depiction of the Lurianic mosaic assembled within the gates of Eitz Chaim demands a resistant reading in which the work is read against itself in the hopes of revealing that which has remained concealed within the text. Rooting himself in the “deep wells of the holy Ari and Gra from who’s milk I have suckled and from who’s water I have drawn and drank” the Leshem seeks to “reveal the cherished light and archival secrets…deep beyond depth, elevated beyond height” that rests at the core of Eitz Chaim. In order to do this, R. Elyashiv works through the text, opening that which was closed through an incessant mode of questioning. Taking no statement for granted, the Leshem examines each idea through a hermeneutics of suspicion where the content of Eitz Chaim is measured and compared to similar and dissimilar concepts throughout the Lurianic corpus. When contradictions and textual ambiguities arise, the Leshem utilizes his unique mode of Kabbalistic analytics (pilpul) in reconciling the opposing texts by clearing a new path in which both statements are seen as augmenting one another. Arming himself with Rashash’s conception of Kabbalistic relativity known as archin, R. Elyashiv interprets Eitz Chaim as a dynamic system whose parts can only be properly understood with an intimate knowledge of their particular context. While the Leshem did undertake the enormity of this task, we have only been left with a biur up to Shaar Ha-Nekudim, Perek Gimmel leaving the majority of Eitz Chaim without commentary. The hundreds of pages it took R. Elyashiv to explicate such a small fraction of Eitz Chaim leaves one pondering the sheer vastness of the Leshem’s vision.

Mitnagdic Kabbalah

From a historical perspective Rav Shlomo Elyashiv served an important role in bridging the gap that existed between the Lithuanian world of the yeshiva and baalei mussar and the world of Lurianic Kabbalah. Throughout his time in Lithuania the Leshem studied Kabbalah with R. Yisrael Meir haKohen Kagan,[26]R. Elya Lopian,[27] R. Yosef Leib Bloch,[28] R. Yitzchak Blazer,[29] R. Yeruchem Levovitz,[30] and R. Yosef Yuzel Horwitz.[31] A more significant, yet historically ambiguous relationship was the purported interaction between R. Elyashiv and the founder of the Mussar movement, R. Yisrael Salanter.[32] The Leshem’s engagement with the various rabbinic personalities-most of who served as leaders of Lithuanian yeshivot- may be viewed through one of two sociohistorical lenses. As an adherent of the school referred to as Kabbalat ha-Gra, R. Shlomo Elyashiv represented a dying breed of mitnagdic-mysticism.[33] While never engaging the political polemics surrounding the mitnagdic/hasidic debate, the Leshem was a strong advocate for a clear and exacting approach to the Lurianic corpus, in contradistinction to the “Hasidic” approach in which the Lurianic system underwent a form of imaginative and psychological revisionism. It is important to note that while the Leshem appears to have associated this mode of interpretation with the “Hasidic” explanation of Kabbalat ha-Ari, he by no means viewed it as a uniquely Hasidic phenomenon. Many of the critiques leveled by R. Elyashiv were in fact directed towards R. Naftali Hertz haLevi, author of Siddur ha-Gra be-Nigleh u-Nistar who represented “those who delve too deeply into the system of Ramchal, interpreting the words of the Arizal as imaginative principles (maareh ha-nevuah).”[34] Nevertheless, by associating with rabbinic personalities who represented the mitnagdic elite, the Leshem maintained his position as a Lithuanian mekubal, one who continued the path of the Vilna Gaon.

Messianic Mysticism

Another possible explanation for R. Elyashiv’s vast interactions with the rabbinic elite of his time has less to do with his spiritual/political predilections and more to do with the Kabbalistic subject matter itself. Following a long tradition in which the expansion and expression of Kabbalistic studies was seen as a fundamental stage within the Jewish eschatological process,[35] the Leshem viewed his historical situatedness as signifying his personal spiritual mission. The spiritual and historical significance as well as the strident dereliction of Kabbalah study that the Leshem saw in his generation may have influenced R. Elyashiv’s emphasis on teaching and sharing his knowledge of chochmat ha-nistar. In one text the Leshem decries what he saw as the rabbinic elite’s disregard of Kabbalah as follows:

“And I am amazed with some of the wise ones of our generation (chochmei ha-dor), for they have no knowledge in this area whatsoever, how can they manage without engaging chochmat ha-emes, that is pnimiyut ha-Torah, and it is strange in their eyes to the point that they know nothing about it. And all of their answers and excuses are meaningless after what is written in Eruvin (55a), “it is not in heaven, and if it was in heaven you must ascend after her, and if she is beyond the sea, you must cross after her,” and it is apparent that this applies to all areas of Torah…including the esoteric aspect (chelek ha-nistar)…and the chelek ha-nistar transcends all other areas [of Torah].”[36]

Elsewhere, R. Elyashiv quotes from R. Yisrael Salanter in describing the unique historical moment in which the secrets of the Torah (sodot ha-Torah) were now accessible to all who were interested:

“And permission has been granted to all those who engage this wisdom to understand these ideas, each according to their level. And specifically from the year taf-reish (1840)[38] and onwards as it is written in the Zohar (2:117), “and in the six-hundredth year of the sixth millennia, the gates of the higher-wisdom (chochma li-ailah) were opened,” and what [the Zohar] meant in writing “opened,” this means to say that permission has been granted to all those who yearn to cleave with the living God (Elokim Chaim), to engage chochmat ha-emes, to enter and to utilize the Name properly. And anyone who delves into this matter will be enlightened and find that this was not the case before the year taf-reish (1840), because then it was still hidden and enclosed, except for a few exceptional individuals, so have I heard in the name of the gaon and chossid R. Yisrael Salanter z”l, and all of this is rooted in the revelation of supernal light that is revealed above and egresses below, as it draws into this world (olam ha-zeh) additional light and the secrets of Torah are revealed in order to rectify (tikkun) the world for the eventual rectification.”[37]

Ignorance coupled with what the Leshem saw as a historically unique time in which sodot ha-Torah were accessible to all may have influenced R. Elyashiv’s drive to engage those rabbinic personalities hitherto unaffiliated with the Kabbalistic system.

R. Elyashiv and R. Avraham Isaac Hakohen Kook

Another significant relationship centered around R. Elyashiv’s expertise in Lurianic Kabbalah was the friendship between the Leshem and the first chief rabbi of Israel, R. Avraham Isaac Hakohen Kook.[39] Serving as a young Rav in the town of Zaumel, Lithuania, R. Kook sought to resolve the “questions and difficulties with some foundational ideas in chochmat ha-nistar” [40] that had arisen in his studies. With permission from the members of his community, R. Kook travelled to Shavel where he spent a month studying and learning from the elder Rav Shlomo Elyashiv. From that point on Rav Kook and the Leshem continued their relationship, exchanging letters, with R. Kook eventually procuring the documents necessary for R. Elyashiv and his family’s move to Jerusalem.[41] R. Kook saw the Leshem as a unique link in the chain of Jewish mysticism, reportedly commenting on the latter’s work Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Hakdamot u-Shearim (Hakdo”Sh) that “from the time of R. Moshe Cordevaro there has been no seferin chochmat ha-emet that grasps and expounds the subject matter like the sefer Hakdamot u-Shearim.”[42] Thanking the Leshem for sending his newly published manuscript, R. Kook wrote: “The house was filled with light upon the appearance of his holy book. I cannot convey to my soul-friend my feelings of inner happiness from the good light. In its yet unbound state, I have already devoured several pages, so enamored am I. It was sweet as honey to my mouth.”[43]R. Aryeh Levin, close student of R. Kook and assistant to R. Elyashiv in Jerusalem describes many nights during which the Leshem and R. Kook would study sifrei kabbalah from midnight until the early morning. R. Kook’s sense of a “divine bond in the depths of the heart”[44]existing between himself and Leshem was reciprocated by the elder R. Elyashiv who saw in the chief rabbi “a vast knowledge and unification of all variant Kabbalistic positions (shitot) and one who has earned the description of “no secret being removed from him” (kol raz lo anis leh).”[45] After the Leshem’s passing shortly after arriving in Jerusalem, R. Kook eulogized the great mekubaland composed the epitaph marking R. Elyashiv’s kever, a lasting testimony to their significant relationship.[46] While there has been no scholarly attempt at identifying the Leshem’s influence on the thought of R. Kook, the overlap in both thinkers approach to the spiritual significance of history as well as the utilization of R. Azriel of Geroni’s concept of the “potential (for) limitation within the unlimited (koach ha-gevul bi-bilti gevul)” is significant. It is important to note that while R. Kook and R. Aryeh Levin appear to have viewed R. Elyashiv’s approach to the Lurianic corpus as authoritative, this was not the case for R. Kooks other students comprising the chug ha-rayah. Both R. Yaakov Moshe Charlop[47] and the R. Dovid Cohen regarded the Leshem’s critical view of Ramchal’s interpretative reading of the Arizal as problematic. While the details of R. Elyashiv’s critical approach towards Kabbalat Ramchal will be discussed in a future essay, it appears that the critique of R. Charlop and R. Cohen, both deeply influenced by Ramchal, was more reactionary than substantive.

Leshem Shevo v-Achloma and the Kabbalists of Beit-El

Described by R. Yosef Chaim of Baghdad as the “lion of secrecy (Ari bi-Mistarim),”[48] it is surprising that R. Elyashiv’s vast body-of-work known generally as Leshem Shevo v-Achloma has been all but ignored by both the traditional and academic schools of Kabbalah study. Within the Haredi network of Kabbalah yeshivot the Leshem’s works are seen as important contributions towards the explication of the Lurianic system, but by no means have they entered the limited curriculum of primary texts comprising the “meforshei ha-Ari.” Only the glosses written by R. Elyashiv under the title ha”ShevaCh(Shlomo ben Chaikl) on the first half of Eitz-Chaim- compiled and printed in R. Menachem Menchin Halperin’s Hagaaot u-Biurim- have received treatment in the writings of sefardi mekubalim.[49] While greatly respected by the sefardic Kabbalists of his day- two works by R. Shaul Dweck ha-Kohen were printed with approbations from the Leshem[50]- his works did not enjoy the same treatment. Those following the sefardic approach to Kabbalat ha-Ari- namely the texts of R. Shalom Sharabi and his students- pay little or no attention to the texts of R. Elyashiv due to the fact that he is considered an adherent of the Vilna Gaon’s school whose focus on the allegorical nature of Kabbalat ha-Ari differs from the attempt to uncover the “depth of the practical meaning”[51] (omek ha-peshat). A point that remains to be shown however, is that while R. Elyashiv did not align himself with the interpretative approach of R. Sharabi and the Kabbalists of Beit-El; he engaged their texts both intellectually- composing a short peirush to Rashash’s Rechovot ha-Nahar[52]- and practically, editing R. Dovid of Agier’s Kuntreis Chasdei Dovid.[53] The Leshem’s respect and engagement with the system of RaSha’’Sh becomes clear with the following passage in which R. Elyashiv praises R. Sharabi’s interpretation regarding shvirat ha-Melachim as a process affecting each particular (prat) as opposed to the collective (Klal) understanding:

“And the words of our teacher Rashash are alive and sustained, and who like him descends to the depths of the abyss, drawing depth from the depths on each statement of the Arizal. We have seen as well by all the great chochmei sefard who have followed him, in particular the great R. Chaim de la Roza in his work Torat Chochom which engraves a path following him at every point, raising vast treasures on all of his words.”[54]

With this level of admiration and engagement with the thought of Rashash the conscious ignorance on behalf of chochmei sefard of R. Elyashiv’ texts becomes more conspicuous. However, a recently rediscovered letter the Leshem wrote to R. Menachem Menchin Halperin helps shed light on the (non)relation between sefardi mekubalim and the Leshem:

“And now my dear friend I will not refrain from informing you that which is within my heart, for I have seen how the great chochmei ha-sefardim- may the supernal sweetness be upon them eternally- align the teachings of our holy teacher R. Shalom Sharabi [in relation] to the teachings of the holy Ari, as they do regarding the oral law in relation to the written law. However in my opinion this does not stand with me. Because regarding the words of the holy R. Shalom may his merit protect us, here I will state that while in truth many of the teachings from his holy words are fundamental and essential regarding the depth of Torat ha-Ari without which it is difficult to grasp the truth; in general his approach is but one facet in the Torat ha-Ari, and it is possible to understand them properly, in my opinion, with other approaches as well, for there are many faces to Torah, and it is not necessary to understand them with his holy path (derech) alone. Furthermore his holy derech is sharp (charif) and very very deep and not every mind can handle this (lav kol moach savil da) and it is possible to understand based on a simpler and easier derech, as I have shown and seen in numerous places that God has graced me with.”[55]

From this letter it is clear that while R. Elyashiv held the Rashash and his derech in high esteem, by no means did he view it as the authoritative and essential approach to the writings of the Arizal. The Leshem’s opinion regarding the teachings of R. Sharabi runs counter to the hyper-essentialism with which the talmidei ha-Rashashviewed his approach. Whether or not this letter was known to the Kabbalists of Beit-El, R. Elyashiv’s stance may have influenced the disassociation from his writings.

Leshem Shevo v-Achloma and Kabbalat ha-Gra

Within the Ashkenazi world of Kabbalah, sifrei Leshem Shevo v-Achloma have experienced a significantly stronger engagement which has been both deeply respectful as well as revisionistic. Considered a student of the Vilna Gaon’s approach to kabbalah, R. Elyashiv differs from the other talmidei ha-Gra in that he had no direct line linking him to the Gra’s teachings. Both R. Chaim Volozhiner (1749-1821) and R. Menachem Mendel of Shklov (d. 1827), considered the main students of the Gra were taught the Lurianic system directly from him. R. Yitzchak Issac Haver (1789-1853), considered peh shlishi in the school of Kabbalat ha-Gra was a student of R. Menachem Mendel of Shklov, and devoted much of his effort towards developing a unifying system wherein the disagreements between the Arizal and the Gra were reconciled.[56] By grafting together the teachings of the Gaon with those of the Arizal in his Pischei Shearim, R. Haver attempts to show that the derech of the Gra is the derech of the Ari. Many of R. Haver’s other writings are direct peirushim on various works of the Vilna Gaon, thus emphasizing his place as an authoritative student. R. Haver’s main disciple, R. Yitzchak Kahane-Kellner- whose three-volume Toldot Yitzchak contains a commentary on the Gra’s peirush to Sefer Yetzirah- spent most of his later years creating institutions in Jerusalem whose sole purpose was to be the study and expansion of the Vilna Gaon’s kabbalistic writings. The Leshem on the other hand had no teacher linking him to the Vilna Gaon, nor did he devote any text to the primary treatment of Kabbalat ha-Gra. Although R. Elyashiv was deemed worthy of editing the writings of the Gra by R. Shmuel Luria of Mohilev and R. Dovid Luria, this did not translate into his works being treated and studied as fundamental texts within the system of Kabbalat ha-Gra.

Current Trends in Leshem Shevo v-Achloma Study

In recent years the writings of the Leshem have seen renewed interest within the Haredi world of Kabbalah study with newly edited editions as well as supplementary works being published. This development however can be divided into two schools of thought; one in which the texts Leshem Shevo v-Achloma are treated as a complex system in which the Lurianic system undergoes an intensive and analytic treatment, thus preserving the difficulty and detailed nature of the text; and one in which Leshem Shevo v-Achloma undergoes a process of simplification for the sake of popularization. Regarding the former, the texts of the Leshem are being edited and reprinted for the primary purpose of textual emendations. In addition, sources as well as footnotes have been added, directing the reader to the source material utilized by the Leshem. Furthermore, various seforim have been published in which the system of the Leshem is treated and clarified. A prime example of this approach is the recently published Yud-Gimmel Maarachot[57] in which the author elucidates the Leshem’s highly complex system of 52 integrated manifestations of the Tetragrammaton that serve as the basic infrastructure running from the recesses of Ein-Sof down to the coarse reality of this-worldliness. This is historically significant in the sense that never before have there been texts solely devoted to understanding R. Elyashiv’s system. With regards to the latter school, the Leshem’s texts have been combed with the redactors culling the philosophical and aggadic material discussing creation, free-will, and matters of faith while discarding the complex Kabbalistic subject matter. The primary example of this approach is the work entitled Shaarei Leshem Shevo v-Achloma (Barzani, 1993), in which R. Yehoshua Edelstein “collected, in full without any change from the holy books Leshem Shevo v-Achloma.”[58] This likkut has two parts; the first contains “a clarification of the fundamentals of faith and worship,” while the second discusses “the order of creation and concatenation (hishtalshlut) in time leading towards the full rectification, may it come speedily in our days.”[59] While the publisher acknowledges that this work serves only as an “opening of the gate to the works of the Rav who is like an angel of God (rav ha-domeh li-malach Hashem) the expert (gaon) in torat emet”[60] it appears to have taken the place of the primary texts for many and as such the actual works comprising Leshem Shevo v-Achloma have been overlooked.

R. Moshe Shapiro: The Popularization of Leshem Shevo v-Achloma

This phenomenon in which the texts of the Leshem undergo the “occasional deletion of a passage so as not to include matters of concealment (nistarot)”[61] for the sake of making them “equal to every searching ben-torah” has taken place primarily within the school of R. Moshe Shapiro and his students. Viewed by many within the Haredi world as the preeminent baal-machshava, R. Shapiro is purported to see in the Leshem- who he describes as “a giant, discordant with the nature of our lowly generation, sent to enlighten our eyes and enable us to grasp a miniscule taste of the depths of torah”[62]- a paradigm of authentic hashkafat ha-torah. In a letter reprinted in Shaarei Leshem[63] at the behest of the Leshem’s grandson R. Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, R. Shapiro explains the rational for publishing a collection of texts taken out of context as follows:

“Many have been asking and searching, who will give us faithful waters to drink from the well of living water, the seforim of our master (the Leshem) that were given over closed (chatumim), and they are yearning to find an opening, one that does not engage the depth of the sugyot in the Zohar and writings of the Arizal. And it is known that many of the drushim open gates in the knowledge of God, the fundamentals of faith and yearning for redemption that each Jew is commanded to know, and in our generation in which the wicked ones surround us and things are “cheapened in the eyes of men” and anything that stands at the height of the world is cheapened and lowered to the dust, it appears to be a “time to act for God” (ait laasot la-Hashem), to open an opening for the masses to the enlightened writings that cleanse the eyes and heal the spirit, that they may swim in them so that knowledge be spread; and I know personally how wondrous the affect these writings have on those who learn them, and even on those who taste from the edge of their sweetness, their eyes shall be enlightened.”

R. Shapiro’s logic is clear, due to the spiritual dereliction of the generation two difficulties arise in learning Leshem Shevo v-Achloma properly. The first is practical in the sense that many have expressed interest in the philosophical aspects of the Leshem’s system without a prior knowledge of the Kabbalistic subject matter. Secondly, the spiritual climate in which the holy is “cheapened in the eyes of men” demands a paradoxical transgressive act for the sake of upholding the law, an “ait laasot la-Hashem.” By utilizing the rabbinic notion of ait laasot R. Shapiro enables himself to support the simplification of the Leshem’s work while simultaneously maintaining the non-ideality of such an undertaking. R. Shapiro’s ambivalence between the ideal sanctity of Leshem Shevo v-Achloma as a unique contribution to the Lurianic system and the real inability of many within the Haredi yeshiva world to grasp the complex subject matter is relieved through the utilization of ait laasot, a temporary disavowal in which the laws governing the revelation of Kabbalistic texts are held in abeyance.[64] Sociopolitical factors notwithstanding, the fact that R. Shapiro acknowledges the ideal treatment of the Leshem’s thought as a self-contained Kabbalistic system is apparent from his involvement with texts that maintain the Kabbalistic and highly complex nature of Leshem Shevo v-Achloma. For example, the abovementioned Yud-Gimmel Maarachot contains a letter of approbation in which R. Shapiro praises the author for “revealing to the light of the world the valuable pnimimin the sugya of yud-gimmel maarachot that our master the Leshem valued and held as the fundamental and root of creation and the revelation of atzilut within the worlds of adam-kadmon; these words are enlightening and deep, and they demand much effort to understand, and few actually learn them…” This ambivalence between the popularization of LeshemShevo v-Achloma and the faithfulness to its complexities is not unique to R. Shapiro; R. Yehoshua Edelstein who compiled Shaarei Leshem has also published Maf’teach Leshem Shevo v-Achloma, a compendium of Kabbalistic sources- from both the Arizal as well as the Vilna Gaon- that appear within the thousands of pages comprising the Leshem’ssystem. In a letter printed at the beginning of Maf’teach, R. Shapiro describes the project as one “whose great significance need not be explained to those who learn such things,” again highlighting the ideality of approaching the texts in a faithful and accurate way. R. Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, grandson and occasional study partner of his maternal grandfather was in possession of a library that contained seforim with glosses and annotations written by the Leshem. Some of these glosses- primarily Kabbalistic in nature- have been printed in Gilyonot Leshem Shevo v-Achloma as well as a recent edition of the journal Yeshurindedicated to the memory of theLeshem. In addition to R. Shapiro and his students, the late Haredi Kabbalist R. Yisrael Eliyahu Weintraub delivered classes on some of the Leshem’s writings, often advising novice students to study Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Sefer Hakdamot u-Shearim as an introductory text.

R. Moshe Schatz: LeshemShevo v-Achloma as Foundational Text

Within the Hasidic world of contemporary Kabbalah study, Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Morgenstern - rosh yeshiva of Yeshivat Torat Chochom - has consistently incorporated the works of the Leshem into his dynamic synthesis wherein the works of the Arizal, Rashash, Baal Shem tov and Gra are grafted together creating new constellations of thinkers who coalesce in a textual matrix described as “secret of secrets” (razin di-razin)[65]. It is R. Morgenstern’s teacher however, who serves as a significant scholar of Leshem Shevo v-Achloma. R. Moshe Schatz- born and raised in Brooklyn- sits in his cramped study in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Givat Shaul teaching the Leshem’s system to a wide range of students, many of whom have studied the Lurianic system extensively only to reach a point of confusion. In a process akin to Derridian deconstruction, R. Schatz leads his students through a process of deliberate unlearning in which the previously held assumptions regarding the Lurianic system are shed.[66] Once the student has moved beyond the preconceived notions that have compounded their confusion, R. Schatz begins to slowly work from the bottom up, elucidating and clarifying the fundamental ideas that the Kabbalistic system is built upon. For R. Schatz the Lurianic system - as refracted through the teachings of Rashash - is a complex structure in which specific concepts undergo a process of repetition through reconfiguration. Utilizing the Lurianic depiction of Partzufim, the works of the Arizal, Rashash, Baal Shem Tov, and the Vilna Gaon coalesce into a unified whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. Building a gestalt of sod, R. Schatz simultaneously reveals the unity that rests beneath the disparate manifestations of Kabbalah throughout history as he removes the commonly held assumptions of machloket that have marked the interpretive approaches of many scholars. According to R. Schatz, these basic concepts such as tzimtzum, reshimu and kav ha-yashar re/present themselves countless times throughout the system, generating a simple pattern in which the general concepts remain the same while the specific details change according to their relative position within the system. This notion of relativity, or archin as the Rashash termed it, has enabled R. Schatz to see in modern quantum physics a valuable model wherein the Lurianic system is mirrored. While R. Schatz utilizes the entirety of the Leshem’s system in explicating his understanding, it is Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Klalei Hitpashtut v-Histalkut (Sefer ha-Klalim) that serves as the primary model for the dialectics of repetition and difference that permeate the Lurianic model. While writing extensively, R. Schatz’s primary publication is his Maayan Moshe (Jerusalem, 2013), an introductory work that serves to guide both the novice and expert towards “a clear understanding of Kabbalat ha-Ari and Rashash.” Maayan Moshe is comprised of three sections; the first serves as an overview of R. Azriel of Gerona’s treatment of the sefirotic arrangement in Biur Esser Sefirot as well as R. Meir ibn Gabbai’s Derech Emunah based on the Arizal and the Leshem; the second section contains a critical edition of both Biur Esser Sefirot and Derech Emunah with footnotes and textual emendations; the third and final section contains a previously unprinted (and now, recently-published) correspondence between R. Elyashiv and R. Naftali Hertz haLevi in which the Leshem clarifies his critique of “those who delve too deeply into the writings of Ramchal” as well as his literalist interpretation of the Arizal’s system. From the hitherto unpublished correspondence R. Schatz shows how indebted the Leshem was to the ideas expressed within the work of R. Azriel of Gerona, namely the conceptual description of Ein-Sof’s“potential (for) limitation within the unlimited (koach ha-gevul bi-bilti gevul),” which as stated above greatly influenced the Kabbalistic approach of R. Avraham Isaac Hakohen Kook as well. R. Schatz continues to teach the Leshem Shevo v-Achloma in a creative approach wherein the ideas of quantum physics, neuroscience and Kabbalat ha-Ari meld together in what he views- based in part on the Leshem’s mystical historiography- as the messianic union of “the lower wisdom of below and the higher wisdom from above.”

R. Meir Triebitz: The Leshem as Authentic Mitnaged

Another current teacher of Leshem Shevo v-Achloma within the Haredi yeshiva world is R. Meir Triebitz who serves as a maggid shiur at Yeshivat Machon Shlomo, a baal-teshuva institute in Jerusalem. R. Triebitz, who also serves as a posek for his community, completed his dissertation in mathematical physics at Princeton University before moving to Jerusalem to teach. Aside from the Talmudic course he teaches, R. Triebitz delivers classes on Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Hakdamot u-Shearim as well as pertinent source materials from the Leshem’s writings. R. Triebitz’s approach is noteworthy in that he maintains that the Leshem’s system is one in which the Kabbalistic system is purified from any pantheistic and acosmic notions. As an adherent to the Vilna Gaon’s interpretation of Kabbalah, R. Triebitz views the Leshem as the last authentic Mitnagdic thinker, fighting both the Hasidic predilection towards pantheism as well as R. Chaim Volozhiner’s revisionism of the Gra’s radical materialism. In supporting his thesis, R. Triebitz highlights the Leshem’s usage of Maimonides’s Guide as well as his literalist approach to the Lurianic system as signifying his attempt to bridge the widening gap separating mysticism and rationality. Of note is R. Triebitz’s usage of philosophical texts- from Kant to Kripke – in an effort to contextualize the evolution of Kabbalistic theology.[67]

Leshem Shevo v-Achloma and the Academic Study of Jewish Mysticism

Within the academic field of Jewish mysticism the apparent ignorance of R. Elyashiv and his works is even more pronounced. While Gershom Scholem does include “Solomon Eliashov’s Leshem Shevo v-Achloma” among the works in which “the basic tenets of Lurianic Kabbalah are systematically and originally presented,”[68] there is no further treatment or analysis of the works. The only other place in which Scholem references the Leshem is in the context of the dialectical process of egression and regression that permeates the Lurianic system. Regarding the tzimtzum and residual reshimu, Scholem writes, that “Throughout this process the two tendencies of perpetual ebb and flow- the Kabbalists speak of hithpasthtuth,egression and histalthkut, regression- continue to act and react upon each other.”[69] In a note on this text Scholem directs the reader to R. Chaim Vital’s Eitz Chaim and adds that “This fundamental idea has been made the basis of the great Kabbalistic system propounded in Solomon Eliassov’s magnum opus Sefer Leshem Shevo v-Achloma. The third volume (Jerusalem 1924) called Klalei Hithpasthuth v-Histalthkut.”[70]

The next academic study that touched upon aspects of the Leshem’s thought was Mordechai Pachter’s 1987 essay Circles and Straightness.[71] In this study Pachter analyzes the Lurianic motif of iggulim v-yosher as described in the writings of R. Chaim Vital and refracted through the teachings of R. Moshe Chaim Luzzatto and R. Yitzchak Isaac Haver. In analyzing the textual contradictions that arise within the works of R. Vital, Pachter utilizes the Leshem’s analytic approach as recorded in Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Chelek ha-Biurim to clear a path of understanding. While there are a few references to the Leshem’s position as a mitnagdic Kabbalist, primarily with regards to his stance on tzimtzum,[72]Pachter does not engage the Leshembeyond the complex details surrounding the topic of iggulim v-yosher.

Following Pachter’s limited treatment of the Leshem, Ron Wacks completed his Hebrew University master’s thesis, “Chapters in the Kabbalistic Doctrine of Rav Shlomo Elyashiv” (1995), in which the Leshem Shevo v-Achloma undergoes the first significant academic treatment. However, it is Eliezer Baumgarten’s master’s thesis “History and Historiography in the Doctrine of Rav Shlomo Elyashiv” completed at the Ben-Gurion University (2006) where the thought of R. Elyashiv is treated in a systematic and significant fashion. Baumgarten analyzes R. Elyashiv’s usage of the historical process, primarily the teleological emphasis that the Leshemplaced on historical temporality. The source material’s utilized by the Leshem, including the writings of the Arizal, Vilna Gaon as well as R. Yisrael Sarug are analyzed as well. It is the relationship between R. Elyashiv and the works of the Ramchal however, that receives the most significant treatment. Baumgarten traces the history of the literal/figurative debate regarding the Lurianic system, touching upon the notion of metaphoric (mashal) versus literal (nimshal) approaches, a topic that will be discussed at length in a future essay. While Baumgarten’s work remains the most extensive and systematic treatment of the Leshem’s system, there is much that remains unanalyzed as well as unthought.

There has been some, albeit limited research regarding the Leshem’s relationship with other mainstream approaches to Lurianic Kabbalah including the sefardic school of Rashash as well as the Hasidic approach to the Arizal’s system. Regarding the former, Jonatan Meir has correctly pointed out R. Elyashiv’s critique of the students of Rashash, or the michavnimin that they saw in R. Sharabi’s approach the only legitimate interpretive stance towards Kabbalat ha-Ari.[73] While Meir does gesture towards R. Elyashiv’s simultaneous critique and admiration for the sefardi mekubalim, his comments are limited to the historical relationship between the two wherein the Leshem“came close to the group of mechavnim, and spent time learning in the Rechovot ha-Nahar yeshiva, even writing a warm letter of approbation for a sefer of kavvanot that was published through the yeshiva.”[74] What is left unexamined is the Leshem’s deep engagement with the system of Rashash, both on a theoretical as well as practical level, manifested through editing and publishing various texts from within the Rashash’s school itself. Meir notes that the instigating factor in the Leshem’s critique of the Rashash’s system was “a difference in approach regarding the relationship between the mashal and the nimshal”[75] within the Lurianic system. Elsewhere[76] Meir suggests that both R. Elyashiv as well as the R. Yehuda Leib Ashlag, the baal ha-Sulam, took issue with the school of Rashash for similar reasons. Namely, that the michavnim were unable to penetrate the depths of meaning within the Lurianic system that were now revealed, a phenomenon- at least for R. Elyashiv - that was symptomatic of the historical epoch. From both sources it appears that Meir conflates the Leshem’s historical/practical critique of the sefardi mekubalim- namely the hyper-essentialism with which they viewed Rashash’s teachings- and the exegetical/theoretical critique that he claims the Leshem held vis a vis the school of Rashah. For Meir the alleged exegetical/theoretical critique was based on a difference of approach regarding the relationship between mashal and nimshal in the Lurianic system, with the Leshemdisagreeing with Rashash. While it is clear, as will be discussed in a future essay, that R. Elyashiv did clear a unique path regarding the literal nature of Lurianic Kabbalah in contradistinction to the figurative approach championed by “those who delve too deeply into Ramchal,” it is difficult to claim that the Leshem’s stance varied from the approach of Rashash.[77]

With regards to the (non)relationship between the Leshem and the Hasidic interpretation of Lurianic Kabbalah, Bezalel Naor, Kana’uteh de-Pinhas (2013) offers a hitherto unpublished correspondence between R. Pinchas Lintop and R. Avraham Isaac Hakohen Kook regarding R. Elyashiv’s Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: Hakdamot u-Shearim. As a Kabbalist, R. Lintop associated himself with the theoretical school of Habad and as such, took issue with the Leshem’s treatment of keilim within the world of Atzilut. While R. Elyashiv was in all probability unaware of R. Lintop’s critique, Naor serves as the Leshem’s surrogate in identifying what in Naor’s eyes serves as the distinguishing factor between R. Elyashiv’s mitnagdic-materialism versus Hasidic-acosmism, or pantheism. While Naor does present a coherent, and correct formulation of the differing opinions regarding the status of vessels (keilim) within the world of Emanation (Atzilut), his exegetical analysis in which the issue becomes analogous with the literal/figurative interpretation of tzimtzum is flawed. As will be discussed in a future essay, the Leshem’s understanding of tzimtzum as a literal event is a complex process resulting in a third category wherein tzimtzum must be viewed as both literal and figurative, or to borrow Elliot Wolfson’s locution it is both “figuratively literal as it is literally figurative.”[78] In addition, Naor’s approach appears to be narrow in scope, culling material from limited sources within the Habad school of Kabbalistic theosophy while quoting from only two sources within Leshem Shevo v-Achloma. From a sociohistorical perspective, Naor - correctly basing himself on R. Lintop’s letter in which the criticism of the Leshemis predicated on Hasidic texts as well as Ramchal’s system- appears to conflate R. Elyashiv’s critique regarding “those who delve too deeply into Ramchal”[79] with an assumed hostility towards Hasidut. While it is a legitimate to assume that as an adherent to the system of the Vilna Gaon, R. Elyashiv viewed Hasidut with a critical eye, I do not believe that the Leshem engaged in the harsh polemics that Naor would associate with him. Firstly, the textual evidence in which the Leshem even hints to Hasidut is extremely limited, with Naor’s main source being a letter written to R. Naftali Hertz HaLevi in 1883.[80] If R. Elyashiv, theoretically following in the footsteps of his spiritual predecessor, the Vilna Gaon, held the same beliefs regarding the danger and heretical leanings of the Hasidic movement, one would assume a more explicit and direct critique within his writings. Taking R. Elyashiv’s harsh criticism of Ramchal as an example,[81] it is apparent that the Leshem was not subtle when it came to those who misinterpreted the Lurianic system. Second, the Leshem quotes at times from texts written by Hasidic thinkers, a minuscule yet significant gesture when coming from the pen of a Mitnagdic Kabbalist.[82] While Naor is in all likelihood correct in that R. Elyashiv disagreed with the Hasidic approach to Lurianic Kabbalah,[83] it is reasonable to claim that the criticism was not nearly as severe as Naor, or R. Lintop for that matter, claim.

A positive exception to the ignorance of R. Elyashiv and his works within the academic study of Jewish Mysticism is Professor Jonathan Garb, who holds the Gershom Scholem chair in Kabbalah in the Department of Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Garb, in his multifarious studies on twentieth-century Kabbalah has consistently gestured towards the significant impact the Leshem has had on individual thinkers as well as the field of Kabbalah study in general. While never offering a critical or comprehensive reading of the Leshem, Garb has pointed out certain significant aspects of R. Elyashiv’s unique approach to Lurianic Kabbalah. Of note is the Leshem’s particular stance with regards to the literal/figurative debate as applied to Kabbalat ha-Ari. As Garb notes in the name of R. Elyashiv, “The main sanctity and importance of the study of Kabbalah is to speak [to the realms] above, not below.”[84] Emphasizing the necessary demetaphorization of Lurianic mashal, the Leshem- as Garb correctly notes- highlights the ontological significance of Kabbalah study.[85] As opposed to the metaphorical readings in which the significance of the Kabbalah is limited to the historical or psychological influence leveled upon the subject,[86] R. Elyashiv calls for a metaphorically-literal reading wherein the Lurianic system maintains its transcendental quality. Garb is correct in pointing out that while the Leshem decries the strictly metaphorical reading of Lurianic Kabbalah, he by no means disregards the historical and psychological significance contained within an immanentist reading of the Kabbalah.[87] While most of Garb’s comments on the Leshem are relegated to tangential points or footnotes, the gesture towards his unique approach is noteworthy.

In situating R. Shlomo Elyashiv within the realm of modern Kabbalah scholarship, my aim is to point towards the significant impact - both historically and theoretically - the Leshem had on the world of Lurianic Kabbalah. While this essay has been primarily focused on the historical context of R. Elyashiv and his works, it is my hope that this serve as an introduction into the gates of the Leshem.[88]

Appendix A: R. Shlomo Elyashiv’s Approbation to R. Chaim Shaul Dweck’s Benayahu Ben Yehoyada: Tikkunei ha-Nefesh (Jerusalem, 1911):

Now it has come before me distinguished in tireless [effort] from the holy land in which God resides a flying scroll, sweet and pleasant, piercingly precious. A sefer enshrined in its clarity. Founded upon the purity of the soul, to purify her and sanctify her in the holy supernal light. And I have seen that it is a clarifying cornerstone, its foundations in the sanctified mountains, built and contained on wondrous and frightening unifications, built and founded upon these two holy Rabbis of Jerusalem, who are, the unique one of the nation- whose holiness is known by all- the holy Rabbi and godly mekubal, holy do we say regarding him, our teacher R. Chaim Shaul Dweck ha-Kohen, may God lengthen his days and years, and his viceroy the Rav, great in Torah and Hassidut in whom the wisdom of god rests our teacher R. Eliyahu Yaakov Lagimi may his days be lengthened and good, they are the builders of this holy edifice, a house for God, a palace for God. However, the essence of this sefer, its roots, branches and fruits belong to our master, the holy of holies, (the) Arizal himself from Sefer Shaar Ruach ha-Kodesh, but these chachamimI mentioned have revitalized her with additional light and great blessing, and they have done great work, holy work that has amazed me. For these yichudim that are in the Sefer Shaar Ruach ha-Kodesh, they contain various yechudim that remain closed off (Torah chatuma) and they necessitate clarification and explanation to unfold their essence, and some (yechudim) need workmanship in order to build them. Even the ones that are simple to understand, they too necessitate a clear order as to how to engage them practically; all of this has been rectified by these chachamimmentioned above, who accordant to their wisdom and righteousness have revitalized all of these yechudimcollected from Shaar Ruach ha-Kodeshand concretized them within this holy sefer, and their wisdom has stood for them in ordering each and every yichud according to the desired intention, to the point that they no longer need any clarification as they remain open to all. They have also organized each and every yichud in an order appropriate for practical usage, and they have organized each yichud with the myriad Holy names that are applicable, and they have written them out explicitly in this sefer so that nothing is lacking for their practical utilization, one will find everything spread before their eyes in the opening of the gates to the holiness of God, and they need but to gaze with the proper intentions at the crowns of the letters that sparkle and shine the eyes in the holiness of the flaming fire of the godly flame. Furthermore, these chachamim have added crowning stones that shimmer with the spirit of God, for their essential goal is to reveal rectifications for the transgressive soul as the result of various transgressions, to reveal to them soul atonement, to save them from descent to the abyss and to enlighten them with the light of the face of the living King, and because it is impossible to rectify each transgression completely as if it never took place, until all of the blemishes that relate to the root soul and the myriad supernal lights are fully rectified, these chachamim have utilized their wisdom with regards to this as well, and they have taken from the teachings of our holy teacher R. Shalom Sharabi who is known for the wondrous teachings that have been revealed to him through supernal gates within the teachings of Arizal, and he has revealed each particular light that dwells in the chambers of the chariot, specifically with regards to the rectifications of the intentions of prayer and mitzvot; these chachamim have taken from his teachings as well and organized according to this the tikkun of each transgression correspondent to each specific light, to draw forth to each one (transgression) the light of yichud specific to each particular transgressions blemish, in order to perfect each tikkun as it applies to the root soul that is rooted in the holy of holies. There is no doubt that yichudim like these are included in our Sages statement (tb. Yoma 86b), “great is repentance wherein transgressions are transformed to merits”. Furthermore, these chachamim have included in this sefer various frightening yichudim that serve to draw forth upon oneself the holy supernal light, as the benefit of those who engage yichudim with purity and sanctity and who privatize their souls with God is known, and they have organized it all in the order necessary for practical engagement and they have intensified the process though all this. For this reason, there is no limit to the measurement of this sefer’s valuable elevation, for it is a jewel that knows no value, and it is worthy for all those in whose heart rests the fear of God to cleave to Him always and to serve as a stamp upon their hearts and a stamp upon their arms, for everything is contingent on the movement from below, as our Sages (Yumah, ch.3) have stated, “Man sanctifies himself a bit, and he is sanctified immensely, from below- he is sanctified above, in this-world- he is sanctified in the next”. These are the words written by the writer for the sake of this sefer’s holiness and practicality, for the merit of the masses, today the 8th of Adar, 1910,

Shlomo Ben R. Chaim Chaikal, author of Sefer Leshem Shevo v-Achloma

Appendix B: R. Shlomo Elyashiv’s Approbation to R. Chaim Shaul Dweck’s Eipha Sheleima al Otzrot Chaim (1907):

I have received what has been sent to me, a few leaves from the planted plaything, with numerous scents from the tents that God has planted, they are the works of the wondrous worker who seeks the concealed depths in all the proper measurements, with the full and righteous measuring stone (Eipha Sheleima v-Tzedek), clarifying and explaining the words of [the] Arizal in the holy and frightening Otzrot Chaim, and from what I have seen here and there, I have seen that it is a worthy and elevated sefer, great is the effort and great is the strength of this great man, the Rav of the land of Israel, the great Rav who contains vast measurements of valuable light, our teacher R. [Chaim] Shaul ha-Kohen may he live long and good days, his ability is great in deepening and widening these concealed teachings that stand at the apex of the world, in the supernal concealment, his strength is great to search and seek this concealed wisdom in her depths and heights, this is the Torah and this is its reward, to reveal the concealed wisdom, and may his wellsprings burst forth so that the masses may enjoy his light that enlightens the eyes of the wise, and to water the masses from his well, the well of living water that rests in the holy and frightening Sefer Otzrot Chaim. These are the words of he who speaks for the honor of the Torahand for the honor of this holy man, the godly mekubal, Kohen to the transcendent God, the wise author may his days be long and good, written and sealed bein ha-mitzarim, erev Shabbos kodesh, the 23rd of Tammuz of this year 1906, waiting with exhausted eyes for the comfort of Zion and Jerusalem,

Shlomo Ben R. Chaim Chiakal Elyashiv

___________________________________________________

Thank you to yedidi Reb Menachem Butler a true "chaver le-dvar naaleh.” Thanks as well to Reb Shlomo Gross for all of his insight and help with this essay.

[1] On the academic history and theosophy of R. Isaac Luria and the Lurianic school of Kabbalah, see Lawrence Fine, Physician of the Soul, Healer of the Cosmos: Isaac Luria and His Kabbalistic Fellowship (Stanford University Press, 2003); Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (Schocken, 1978), 244-286; Ronit Meroz, ''Redemption in Lurianic Teaching,'' (PhD dissertation, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1988; Hebrew); Moshe Idel, “‘One from a Town, Two from a Clan’: The Diffusion of Lurianic Kabbala and Sabbateanism: A Re-Examination,” Jewish History 7:2 (Fall 1993): 79-104; Elliot R. Wolfson, “Divine Suffering and the Hermeneutics of Reading: Philosophical Reflections on Lurianic Mysticism,” in Robert Gibbs and Elliot R. Wolfson, eds., Suffering Religion(London: Routledge, 2002), 101-163; Morris M. Faierstein, “From Kabbalist to Zaddik: R. Isaac Luria as Precursor of the Baal Shem Tov,” in Leonard J. Greenspoon and Ronald A. Simkins, eds., Spiritual Dimensions of Judaism Omaha (NE: Creighton University Press, 2003), 95-104; Shaul Magid, From Metaphysics to Midrash: Myth, History, and the Interpretation of Scripture in Lurianic Kabbala(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008), Morris M. Faierstein, “Traces of Lurianic Kabbalah: Texts and their Histories,” Jewish Quarterly Review 103:1 (Winter 2013): 101-106, among other sources. See also my forthcoming essay, “Metaphoric Literality: The Leshem and Lurianic Kabbalah.”

[2] On the formulation of the Lurianic corpus, see Yosef Avivi, Kabbalat HaAri (Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, 2008), three volumes.

[3] Regarding the complex dialectic of concealment and secrecy in Jewish mysticism, see Elliot R. Wolfson, Language, Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York: Fordham University Press, 2005), 200-224; Elliot R. Wolfson, Open Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision of Menahem Mendel Schneerson (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 28-66.

[4] See Rav Chaim Vital, Hakdamah li-Shaar HaHakdamot, printed in R. Chaim Vital Sefer Eitz Chaim (Jerusalem, 1985), 5-24; Rav Tzvi Hirsch Eichenstein, Tzur Me-Rah v-Asseh Tov (Bnei Shlishim, 2004); Louis Jacobs, Turn Aside From Evil and do Good: An Introduction and a Way to the Tree of Life(London: Littman Library, 1995).

[5] On Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto and his systematic approach to the Lurianic system, see Isaiah Tishby, Messianic Mysticism: Moses Hayim Luzzatto and the Padua School, trans. Morris Hoffman (London: Littman Library, 2005); Jonathan Garb, Kabbalist in the Heart of the Storm: Rabbi Moshe Hayyim Luzzatto(Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Press, 2014; Hebrew); Mordechai Chriqui, Rehev Yisrael: Kabbalat R. Moshe Chaim Luzzatto (Machon Ramchal, 1995); and Elliot R. Wolfson, “‘Tiqqun ha-Shekhinah’: Redemption and the Overcoming of Gender Dimorphism in the Messianic Kabbalah of Moses Hayyim Luzzatto,” History of Religions 36:4 (May 1997): 289-332. For a socio-historical treatment of Ramchal and colleagues, see Elisheva Carlebach, “Redemption and Persecution in the Eyes of Moses Hayim Luzzatto and His Circle,” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 54 (1987): 1-29; and Jonathan Garb, “The Political Model in Modern Kabbalah: A Study of Rabbi Moses Hayyim Luzzatto and His Intellectual Surroundings,” in Benjamin Brown, Menachem Lorberbaum, Avinoam Rosenak, Yedidia Z. Stern, eds., Religion and Politics in Jewish Thought: Essays in Honor of Aviezer Ravitzky, vol. 2 (Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute and Merkaz Zalman Shazar, 2012), 533-565 (Hebrew).

[6] For a historical overview of Rav Shalom Sharabi and his system of Kabbalistic theurgy, see Pinchas Giller, Shalom Shar’abi and the Kabbalists of Beit El (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008); Jonatan Meir, Rechovot HaNahar: Kabbalah and Exoterica in Jerusalem (1896-1948)(Jerusalem: Hebrew University Press, 2011), 19-74. For an in-depth depiction of Sharabi’s approach to the Lurianic system, see Rav Yaakov Hillel, Ahavat Shalom: Yesodot u-Klalim bi-Torato shel Maran HaRashash (Ahavat Shalom, 2001). On Rav Yaakov Hillel, see Jonatan Meir, "The Boundaries of the Kabbalah: R. Yaakov Moshe Hillel and the Kabbalah in Jerusalem," in Boaz Huss, ed., Kabbalah and Contemporary Spiritual Revival (Beer Sheva: Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Press, 2011), 163-180.

For a recent, massive work devoted to Rav Sharabi’s system, approach and relationship vis-a-vis other Kabbalistic schools, see Shmuel Ehrenfeld, Yar’ucha Im Shemesh: Klalim bi-Derech Limmud Torat HaRashash (Yam HaChochma, 2014). The interface between the Rashash, psychoanalysis and the philosophy of Merleau-Ponty will be discussed in my forthcoming essay, “Hitklalut u-Hitkashrut: Individuation, Depth and Coming to be.”

[7] While the bibliography on Hassidut is immense, I will limit the sources to works that deal primarily with the Hasidic (re)vision of Lurianic Kabbalah, See Elliot R. Wolfson, Open Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision of Menahem Mendel Schneerson (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 24-43, for a discussion of the transmutation of the Lurianic system unto a Hasidic/Messianic register. See Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (New York: Schocken, 1978), 325-350; Rachel Elior, The Paradoxical Ascent to God: The Kabbalistic Theosophy of Habad Hasidism (Albany: SUNY Press, 1993), 5-18; Naftali Loewenthal, Communicating the Infinite: The Emergence of the Habad School (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1990); Rivka Schatz-Uffenheimer, Hasidism as Mysticism: Quietistic Elements in Eighteenth-Century Hasidic Thought, trans. Jonathan Chipman (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993); and Zvi Mark, Mysticism and Madness: The Religious Thought of R. Nachman of Bratslav (London and New York: Continuum Books, 2009), 28-60; 185-200.