Rabbi Zeira – Forgetting the Teachings of Babylon

By Chaim Katz

We read in the Talmud (Baba Metziah 85a):

R. Zeira, when he moved to the land of Israel, observed a hundred fasts to forget the teachings of Babylonia, [1] so that they should not disturb him.

He fasted another hundred times so that R. Elazar should not die during his years and the responsibilities of the community not fall upon him.He fasted another hundred times so that the fire of Gehenna should have no power over him.

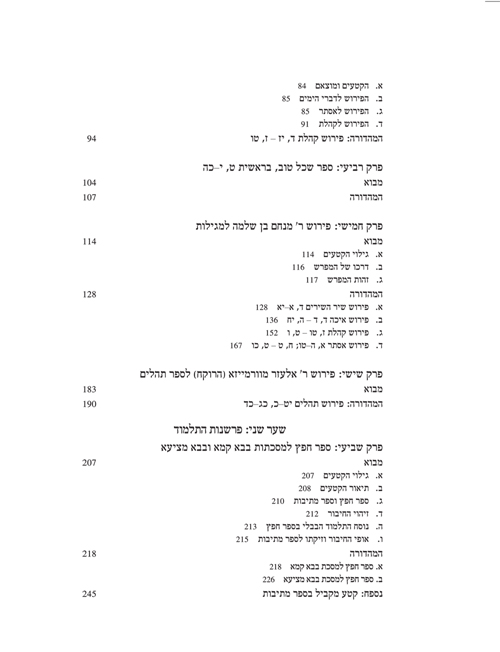

Figure 1 From the first print of Baba Metziah Soncino, Italy 1489

There are some difficulties with R. Zeira forgetting the teachings of Babylonia:

1) Both the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmud contain many interactions between sages who travelled from the land of Israel to Babylon or from Babylon to the land of Israel. These sages shared their own teachings and traditions with their counterparts. By forgetting Babylonian teachings, R. Zeira is choosing not to participate in this knowledge transfer. Why? [2]

2) R. Zeira is mentioned many times in the Jerusalem Talmud and sometimes he transmits in the name of his Babylonian teachers. Many of these exchanges clearly took place when he already was in the land of Israel. How can he transfer Torah information that he has supposedly forgotten? [3]

3) The Talmud (Shabbat 41a) relates that when R Zeira was about to leave for the land of Israel, he went out of his way to hear one more teaching from his teacher, Rav Yehuda. Why would he go to the trouble of amassing more Babylonian teachings if he intended to immediately forget them?

4) Forgetting one’s learning purposefully isn’t a pious thing to do. The Mishna Pirkei Avot 3:10 strongly discourages it, as does the Talmud: R. Elazar said: One who forgets a word of his learning (Talmud)causes his descendants to be exiled – Yoma 38b. Resh Laqish said: One who forgets a word of his learning (Talmud) transgresses a negative commandment – Menachot 99b.

We can find a simple solution to these questions in oneof the manuscripts of Baba Metzia, written around 1137 and housed in the National Central Library in Florence. The manuscript disagrees with the premise that R. Zeira ever forgot his learning:

R. Zeira fasted so that he would notforget the teachings of Babylon.

He observed another forty fasts so that R Il'a should not die in his lifetime.

Figure 2 Florence Manuscript BM 85a

As far as I know, this manuscript is unique among the manuscripts that exist today in defining “not to forget” as the purpose R. Zeira’s fast. [4] The manuscript is also attractive for a couple of other reasons:

The passage is shorter here than in the standard version. The explanations “when he moved to the land of Israel”, “so that it should not disturb him”, [5] “so that the responsibilities of the community not fall upon him” are all missing. This reduction most likely indicates that the manuscript reflects an early version of the story – a version in which marginal commentary had not yet been copied (inadvertently) into the text.

The paragraph that precedes the story of R. Zeira (in all versions) tells of Rav Yosef (R. Zeira's colleague) who also observed a series of three sets of forty intermittent fasts. The purpose of Rav Yosef’s fasts was to guarantee that the knowledge of the Torah would not depart from himself, from his children and from his grandchildren. The goal of Rav Yosef's fasts seems to agree with the goal of R. Zeira’s fasts; to remember (i.e., not forget) the teachings of Babylonia.

According to this manuscript, all of R. Zeira’s fasts have something in common with each other. He fasted so he would not forget, he fasted so that R. Ila'i would not die, and he fasted so that the fire of Gehina would not harm him. He always seems to be fasting so that something should not happen.

However, many authorities have discussed the standard version, and no one (as far as I know) has relied on this reading to resolve the original questions. [6]

Here are some of the classical interpretations that attempt to solve the problems of R. Zeira’s forgetting.

Rashi writes (BM 85a) that the students in the land of Israel were not בני מחלוקת, were not contentious, ונוחין זה לזה, they were pleasant to each other] . . . ומיישבין את הטעמים בלא קושיות ופירוקין and they explained their reasoning without challenging each other with difficulties and rebuttals.

According to Rashi , R. Zeira forgets the “atmosphere” of the Babylonian academies. [7]

Maharsha (1555-1631), disagrees with Rashi. He argues that the sages in the land of Israel do engage in questioning and answering like their counterparts in Babylonia. He cites the Gemara (Baba Metzia 84a) where R. Yohanan says about Reish Laqish: he would raise twenty-four objections, and I would reply with twenty-four answers.

Therefore, Maharsha explains that possibly the Babylonian piplul was faulty and similar to a style of piplulthat existed in his own time דוגמת חילוקים שבדור הזה. He objects to this style of questioning and answering because it distances one from the truth, and can’t help one rule on halakhic issues. Accordingly, R. Zeira fasted in order to forget how to piplul the Babylonian way.

Abravanel (1437-1508) in his commentary on Pirkei Avot (on the Mishna in chapter 5 which begins: There are four types who study with the sages) writes somewhat similarly. The problem with the one who is compared to a sponge, who soaks up everything – is that he retains things that are untrue. In the search for truth, there are necessary steps which themselves are untrue: כי לא תברר האמת כי אם בהפכו truth can only be evaluated when compared with its opposite. R. Zeira fasts to forget the stages in the arguments of the Babylonian Talmud that were untrue.

In summary, all three of these interpretations agree that R. Zeira didn’t literally forget the Babylonian teachings. He forgot the “atmosphere” of the Babylonian academies or the interim discussions that took place there. [8]

I’d like now to give some examples of how the story of R. Zeira is presented in some early Hassidic sermons, to show how the Rebbes and their audiences understood the story of R. Zeira. These sources aren’t concerned with explaining our Gemara; R. Zeira’s story is cited to support an ethical or moral lesson.

Torah Or is a collection of sermons by R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812). On page 69c, in a discussion about spiritual worlds, the author says:

The purpose of the river diNur, (fiery river (or maybe fiery light)), in which the soul submerges itself as it passes from this world to Gan Eden, is to erase its memories of this physical world. If the soul remembers its encounter with materiality, it can’t experience Gan Eden. And when the soul goes from the lower Gan Eden to the higher Gan Eden it also must pass through a river diNur to forget the comprehension and pleasures of the lower Gan Eden. (Zohar part 2 210a) This is the idea in the Gemara: R. Zeira observed 100 fasts to forget the Talmud of Babylonia even though he had studied it with devotion.

In Likutei Moharan (ch. 246), R. Nachman of Bratslav (1772 – 1810) writes:

A person sometimes has to feel self-importantגדלות, as it says (2 Chronicles 17:6) His heart was elevatedויגבה לבו in the service of G-d. This helps the same way as fasting helps. For when one needs to attain an understanding or needs to reach a higher level, he has to forget the wisdom he had previously acquired. R. Zeira fasted to forget the Talmud of Babylon in order to reach a greater level of comprehension – the level of the Talmud of the land of Israel. Similarly through self-importance, one forgets his wisdom . . .

In these examples of Hassidic thought there is no difficulty with the idea that R. Zeira forgets his learning in order to reach higher spiritual plateau. Forgetting is a purification process that is both necessary and exemplary. [9]

Returning now to the literal sense of the Gemara:

R. Issac Halevi (Rabinowitz) (1847-1914), the author of Dorot Harishonim addresses our problem in a footnote (Dorot II p 427 footnote 93). He posits that in R. Zeira’s time there were already two canonized collections of Talmudic material arranged around the Mishna; each in its own distinct form and style.

כבר הי׳ להם סתמא דהש"ס על המשנה שגרסו כבר במטבע קבועה, וכן הי׳ להם אז כבר גם בארץ ישראל.

R. Zeira chose to forget the Babylonian Talmud (as it existed in his time), because it interfered with his studies in the land of Israel.

According to this interpretation, R. Zeira forgot only the redaction or arrangement of the teachings he had learned. He didn’t forget the teachings themselves (or the study method). [10]

I’d like to suggest an original explanation. It’s based on passages in the Talmud about R. Zeira and additionally can explain why only R. Zeira decided to forget the teachings of Babylon when he moved to the land of Israel.

1) R. Yitzhak b. Nahmani said in the name of R. Eleazar: The halakha agrees with R. Jose b. Kipper. R. Zeira said: “If I merit, I'll go there and learn the halakha from the Master himself”. When R. Zeira came to the land of Israel he found R. Eleazar and asked him: “Did you say: The halakha is in agreement with R. Jose b. Kipper?” – Nidda 48a

2) R. Zeira said to R. Abba b Papa: When you go there, detour around the Ladder of Tyre and visit R. Yaakov b Idi. Ask him if he heard from R. Yohanan if the Halakha is like R. Aqiba or not – Baba Metziah 43b

3) R Zeira, commented: How can you compare R Binyamin b Yefet’s version of R. Yohanan’s statement with the version of Rabbi Hiya b Abba. R Hiya b Abba was precise when he studied the halakhic traditions from R Yohanan but R. Binyamin b Yefet was not precise. Moreover, R Hiya b Abba reviewed his learning (Talmud) with R. Yohanan every thirty days. – Berachot 38b

4) R. Nathan b. Tobi quoted R. Johanan . . . Rabbi Zeira asked: “Did R. Johanan say this?” Yes, he answered. Rabbi Zeira recited this teaching forty times. R. Nathan said to R. Zeira: Is this the only teaching that you have heard or is it a teaching that is new to you? R. Zeira replied: “It's new to me. I wasn't sure if it was taught in the name R. Yohanan or R Yehoshua b Levi.” – Berachot 28a

We see that the teachings of the land of Israel (especially R. Yohanan’s) did reach R. Zeira while he was still in Babylon [11]. R. Zeira, however, didn’t really trust these teachings. Sometimes he thought they were attributed incorrectly, or their content was not accurate. He doubted if a statement in the name of R. Eleazar was correct. [12] He was unsure if R. Yohanan agreed with R. Aqiba’s position or not. He distinguished between the different amoraim who transmitted teachings. In general he looked at Torah that reached Babylon as something that was possibly unreliable, inaccurate or “damaged in transit”.

R. Zeira was only able to resolve his doubts when he moved to the land of Israel and learned the Torah of the land of Israel there. He then forgot the imprecise version of these teachings that he had previously memorized in Babylon – “the teachings of Babylon”. He could forget them because they were superseded by accurate teachings that he now received in the land of Israel. [13]

I’d like to thank Reb Gary Gleam who provided the cabbage rolls and coffee, and the late night sounding board.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] תלמודא בבלאהis sometimes translated as Babylonian Talmud, which I think is an anachronism. I will use the translation “Babylonian teachings”. All the available manuscripts have תלמודא דבבל = the teachings of Babylonia. The phrase Talmuda dBabel or TalmudaBabelah occurs only here (Google). Talmud in the sense of teachings occurs many times, often in comparison to mikra or mishna.

[2] Compare Rosh Hashana 20b: “When R. Zeira went up [to the land of Israel], he sent [a letter] to his colleagues [in Babylonia] . . .” R. Zeira didn’t break off all contact with the old country. He taught them what he heard and learned in the land of Israel.

[3] See Goldberg, Abraham. “Rabbi Ze'ira and Babylonian Custom in Palestine” (Hebrew) Tarbiz vol. 36 1967 (pages 319-341), for examples of Babylonian traditions that R. Zeira brought to the land of Israel. The following quote is from the online abstract:

“R. Zeira is the outstanding figure among many who came from an area of unmixed Babylonian tradition and who tried to impose their own Babylonian practice upon Palestinian custom.”

[4] The crucial word דלא, is crossed-out in the manuscript, but I’m assuming that the strikethrough is not the work of the original sofer. (Didn’t scribes write dots on top of the words they wanted to erase?) The facsimile shows a number of other emendations that were written after the manuscript’s creation.

[5] The words “so that it should not disturb him” would be out of place in this version of the story, since according to this version, R. Zeria never forgot the Babylonian teachings, but the idea is that the text is short. There is a geniza fragment from The Friedberg Project for Talmud Bavli Variants and it is equally as short. (Note that it matches the standard editions with regard to the goal of R. Zeira’s fast.)

Figure 3 Geniza fragment of our Baba Metziah 85a

Translation of the geniza fragment:

R. Zeira observed forty fasts to forget the teachings of Babylon.

He fasted another forty times that R Il'a should not die in his lifetime.

He fasted another forty times that the fire of Gehenna should have no power over him.

[6] The author of Dikduke Soferim mentions this version but doesn’t suggest that its reading is better than the standard one. Dikduke Sofreim has written elsewhere that this specific manuscript belonged to Christians who translated (into Latin) passages that were regularly used against Jews in inter-faith disputations. There’s no Latin on this page, but you can see Latin on some other pages.

[7] Rashi mentions his source as Sanhedrin 24a. He understands that the students of Babylon were antagonistic to each other unlike the students in the land of Israel who were pleasant to each other. Rashi apparently was thinking of this in his commentary on the prayer of R. Nehunya ben HaKanah – Berachot 28b. The prayer reads: “May it be Your will that I don’t make a mistake in a halakhic ruling, and that my colleagues rejoice with me . . .” Rashi understands the prayer this way – May it be Your will that I don’t make a mistake in a halakhic ruling and my colleagues make fun of me.

[8] The explanations of Maharsha and Abravanel have prompted subversive interpretations by the school of the German Jewish historians of the Talmud. In the Soncino translation of Shabbat 41a, the translator, Rabbi DR. Freedman (1901-1982) writes: “Weiss, Dor, III, p. 188, maintains that R. Zera's desire to emigrate was occasioned by dissatisfaction with Rab Judah's method of study; this is vigorously combatted by Halevi, Doroth, II pp. 421 et seq.”

Jacob Neusner’s in his book A History of the Jews in Babylonia page 218, also questions the idea that sages of the land of Israel rejected the Babylonian methods of study, and finds “Halevi’s strong demurrer quite convincing”.

[9] In this context, the Talmudic statement: גדולה עבירה לשמה ממצווה שלא לשמה - מסכת הוריות י'ע"בmay be somewhat relevant.

[10] I’m not sure, according to R. Halevi, did R. Zeira also forget the anonymous Talmudic layer (stam or redactor) that existed in his time?

[11] The first of these conversations definitely took place in Babylon. The fourth interaction occurred in the land of Israel but revises a teaching that R. Zeira probably heard in Babylonia. The middle two quotes are may describe R. Zeira in Babylon, but even if they occurred when R. Zeira was already in the land of Israel, they reflect doubts that he had while in Babylon. The number 40 in the last example is also remarkable. He repeats something 40 times in order to remember. He fasts 40 times to forget.

[12] R. Eleazar teaches without citing his source but everyone knows that his teachings are R. Yohanan’s (Yerushalmi Berakot 2:1 and Yerushalmi Shekalim 2:5).

[13] R. Zeira didn’t forget the native Babylonian teachings, authored and recorded by the Babylonian amoraim. He never doubted their accuracy. He brought those teachings to the land of Israel and enriched the Torah of the land of Israel with them.