Assorted Comments on R. Jacob Emden, Ashkenazic Views of Sephardic Gedolim, and More

by Marc B. Shapiro

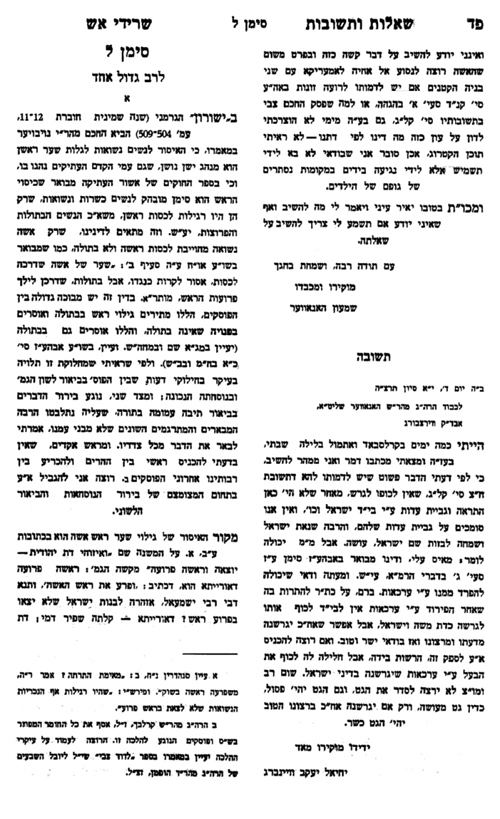

1. Since I have discussed R. Jacob Emden in many posts, let me add the following. If you examine Emden’s Birat Migdal ha-Oz you find that he refers to himself as הסריס. Here is the Berditchev 1836 edition of the work, p. 135a.[1]

I think all would agree that this is a strange title to give oneself. In this work, p. 116a, he also calls himself שלו.

On pp. 101b and 102a he refers to himself as שכוי.

Here is Lehem Shamayim (Wandsbeck, 1728), vol. 1, p. 1a (see also 2a) where he also refers to himself as שכוי.

![]()

What is this all about? The answer was revealed by R. Meir Segal in his 1881 commentary on Emden’s siddur (although I am sure many people had already figured it out).[2] The gematriyot of all these words are either 335 or 336. This corresponds to יעקב בן צבי, the gematria of which is also 336 (and we know that gematriyot are allowed to be off by one number).

Emden writes:

סוד פורי"ים בקצור רומז ג"א ממותקים בג"ה (ס"ה של"ו הוא בה"ס . . .)

As R. Segal explains,[3] this is to be “translated” as:

סוד פורים בקיצור רומז ג'א-להים ממותקים בג'הויות ס"ה גימטריא של"ו הוא בעל הספר

ס"ה obviously stands for סך הכל and what it is saying – ignoring the kabbalistic allusion – is that the gematria of פורים equals 336 and this is also equaled by א-להים x 3 = 258 + הויה x 3 = 78 (258+78=336)..

As mentioned, Emden refers to himself as שלו. How is this supposed to be pronounced? Some people would assume shelo. I originally thought that a more likely meaning was shalev, which means “calm” or “tranquil”. R. Segal also understands it this way since he writes[4] כנה א"ע בשם שלו כי השלום יאות לבוטח

Shilo is also sometimes spelled as שלו so that is another possibility.

However, these suggestions are incorrect, and the proper way to pronounce it is selav, as in quail. We know this because of the verse in Psalms 105:40:

שאל ויבא שלו ולחם שמים ישביעם

The second half of the verse has the words לחם שמים. This is the name of Emden’s commentary on the Mishnah. I am certain that the connection of שלו and לחם שמים was regarded as significant by Emden, and this also reveals how שלו should be pronounced.[5]

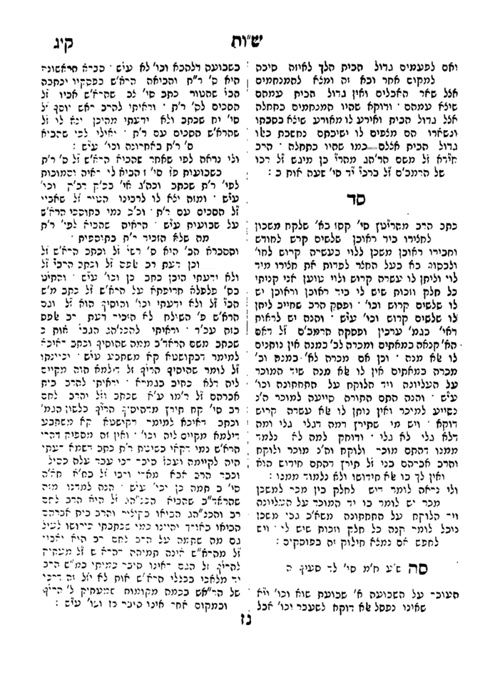

2. In Changing the Immutable, p. 205, I cite a letter from R. Elhanan Wasserman to R. Eliezer Silver and note that the published version of the letter, in Kovetz Ma’amarim ve-Iggerot, vol. 2, p. 97, omits R. Wasserman telling R. Silver that before R. Hayyim Ozer Grodzinski’s death the latter reached for his wife’s hand. R. Moshe Maimon informed me that the letter with the deleted words restored was published in R. Pinchos Lipshutz, Peninei Hen (Monsey, 2000), pp. 76-77. Here it is.

![]()

![]()

From the original letter we can see that R. Hayyim Ozer’s comment that things are not good was made to his wife. However, one who reads the letter in Kovetz Ma’amarim ve-Iggerot would have to conclude that this statement was made to R. Elhanan, as the passage reads:

שעה קלה לפני הפטירה . . . אמר: "דוא וויסט עס איז ניט גוט" (אתה יודע שהמצב אינו טוב)

As I mentioned in the book, I think it is significant that the publisher inserted three dots showing that something was deleted, since this is very uncommon among haredi publishers. But the following is also important: In the original letter R. Elhanan writes אמר לה, meaning that R. Hayyim Ozer made this comment to his wife. Also (and this point was made to me by Maimon), in the Hebrew translation what appears is אתה יודע which is masculine and indicates that the comment was made to R. Elhanan. These changes had to be made since once the line about holding his wife’s hand is removed, it would not make sense for the reader to see a reference to a woman, as in אמר לה.

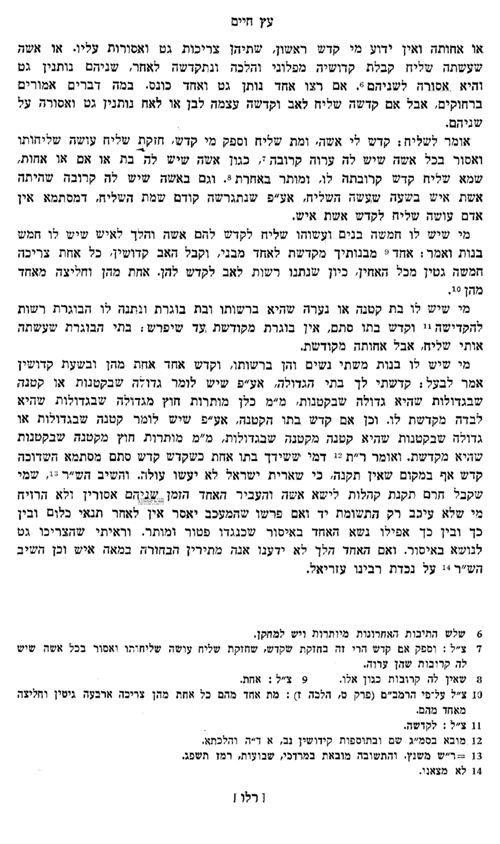

Maimon also called my attention to the following: Here is a famous painting portraying Napoleon granting freedom to the Jews. Notice how Napoleon appears like Moses, holding a Tablet of the Law.

![]()

Here incidentally is another image from a coin minted on the occasion of the meeting of the Sanhedrin summoned by Napoleon. Notice how Napoleon is handing the Two Tablets of the Law to Moses. In other words, Napoleon is portrayed as God.[6]

![]()

Returning to the painting of Napoleon, it is reproduced in R. Binyamin Shlomo Hamburger’s Meshihei ha-Sheker u-Mitnagdeihim (Jerusalem, 2009), p. 481, yet here sleeves have been added to the woman.

Since I have just mentioned R. Moshe Maimon, let me continue with a couple of his comments. In my book, p. 97 n. 67, I translate minhag vatikin[7] as a “long established practice”. I actually should have said “long established practice of the pious ones” (although some might see this as already implied). Maimon questions whether there is any relationship between vatikin and “long established”, or it if just means “the pious ones”. I always assumed that vatikin means the “pious ones of old”. Indeed, Jastrow translates the word as “the conscientiously pious men of former days”, and an online search reveals that others translate similarly.

Yet Rashi, Berakhot 9b, explains vatikin as אנשים ענוים ומחבבין מצוה, and in this explanation there is no assumption that the vatikin lived in former days. In other words, a practice developed by contemporary pious ones could also be regarded as a minhag vatikin, and there appears to be no reason for me to have thought that Rashi would assume that the vatikin he describes were also “men of old”.

While modern Hebrew uses the word vatik to mean old or one involved in something for a long time, e.g., מוותיקי הסופרים, I have to acknowledge that, with apparently one exception (see note 8), I have not found early uses of the term that have this connotation. One who paid attention during the High Holidays liturgy would have noticed the term and it has nothing to do with “old” here, e.g., הועד והותיקות, לותיק ועושה חסד, and others.[8] See also Arukh, ed., Kohut, s.v. ותק, which offers Arabic and Greek cognates that have no connection to age. For those really interested in the topic, you should consult David Golinkin’s learned and comprehensive article which also shows that the term vatikin has no connection to age.[9]

Maimon also made the following correction. On p. 229 n. 64, I refer to R. Hayyim Eleazar Shapira’s criticism of Slobodka students and his negative view of R. Moses Mordechai Epstein, and note that this was removed from some editions of R. Moses Goldstein’s Mas’ot Yerushalayim.[10] The censored material I refer to is from a conversation between R. Shapira, the Rebbe of Munkacz, and R. Solomon Eliezer Alfandari, and contrary to what I carelessly wrote, what was deleted was stated by R. Alfandari, not R. Shapira. This matter, and the censorship, is discussed by Maimon in a Seforim Blog contribution here.

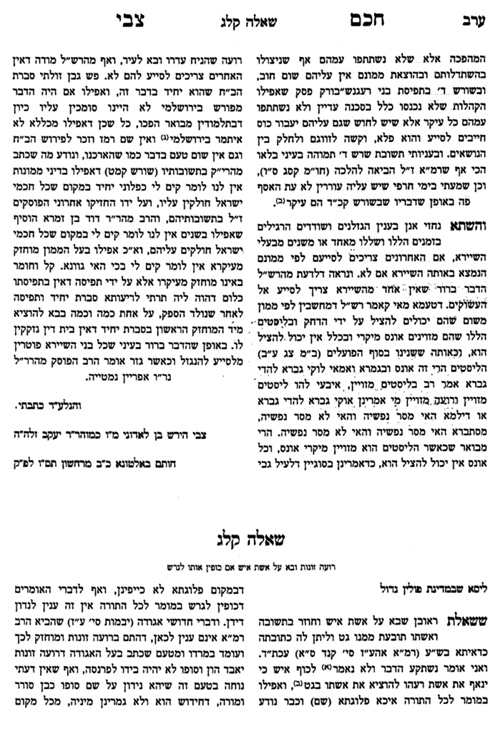

Let me offer another example where Mas’ot Yerushalayim is censored (and this is not noted by Maimon in his post just mentioned). Here is Mas’ot Yerushalayim (Munkacz, 1931), pp. 91a-91b.

![]()

![]()

It mentions that after R. Alfandari’s death his writings were under the control of certain Sephardic rabbis who were associated with the Chief Rabbinate. These rabbis are referred to as .איזה רבני ומלקקי המשרד מהצפרדעי"ם The last word, צפרדעים (frogs) is a play on ספרדים.

Here is how the page looks in a later edition published in Israel (pp. 319-320). As you can see, the reference to the צפרדעים has been deleted.

![]()

Needless to say, Sephardic readers were not pleased to see this. But this wasn’t the only thing to upset them. Earlier in the book (pp. 26a-b in the first edition), we find that R. Shapira stated that he heard from R. Yehezkel Shraga Halberstam of Sieniawa that when the latter was in Jerusalem on the yahrzeit of R. Hayyim ben Attar, the Or ha-Hayyim, he observed that the Sephardim did not visit his grave. He inquired about this and was told that even though the Or ha-Hayyim was a Sephardi, he had disputes with the Sephardim and the latter did not recognize his greatness. Referring to the Sephardim, he quotes Psalms 82:5: “They know not, neither do they understand; they go about in darkness.” This is contrasted to the Ashkenazim who give the Or ha-Hayyim his proper respect.

When Mas’ot Yerushalayim appeared, R. Meir Vaknin, the rav of Tiberias, was quite angry upon seeing the two texts I have discussed and responded sharply.[11] He completely rejects the notion that the Sephardim do not properly respect the Or ha-Hayyim. He also denies that there was ever a dispute between the Sephardic community and the Or ha-Hayyim.

Why then do the Sephardim not go to the Or ha-Hayyim’s grave on his yahrzeit? R. Vaknin explains that the reason is simple, namely, that Sephardim don’t have this minhag and they were never taught to do so by R. Isaac Luria. Therefore, they don’t go to graves on any yahrzeit, “not to the ARI, not to Maran the Beit Yosef, and not to the Rambam. Even to Rabbi Shimon Ben Yohai only a very small number go to Meron.”

R. Vaknin is speaking about the Sephardic community in the Land of Israel before the massive aliyah of the North African Jews. Today, of course, Meron is full of Sephardim on Lag ba-Omer (which people mistakenly believe to be the yahrzeit of R. Shimon Ben Yohai[12]), but R. Vaknin provides testimony about how things were very different not too long ago.

As for Mas’ot Yerushalayim referring to Sephardim as צפרדעים, R. Vaknin is simply outraged by this insult:

והאם טוב וישר הדבר הזה בעיני א-להים ואדם לכתוב ולכנות שם רע על העם הקדוש הספרדי כולו בכללותו, מי יוכל להתאפק על בזיון ושם רע על כללות עם הקודש, ואיזה תקון יועיל לכלות העון הזה ולהתם הפשע החמור, אפילו המכנה שם רע לחברו עיין ברז"ל כמה חמור ענשו, וכל שכן על כללות העם כולו אשר כמה וכמה גדולי תורה נמצאים בתוכו, כמה צדיקים וחסידים וסובלי חולאים וסיגופים ותעניות לכבוד ה'ותורתו נמצאים בתוכו

R. Vaknin also printed a letter by R. Jacob Zarihan of Tiberias. He too was very upset by what appears in Mas’ot Yerushalayim.

The 2004 edition of Mas’ot Yerushalayim has Goldstein’s reply to R. Vaknin in which he apologizes if he caused offense.[13] He stresses that his negative words about the צפרדעים were only made with reference to those Sephardic rabbis associated with theמשרד , i.e., the Chief Rabbinate.[14] This could hardly have been of any comfort to R. Vaknin since unlike the Ashkenazic world, the Sephardic world did not have an extremist Edah Haredit, and almost all of the Sephardic rabbis had great respect for the Rishon le-Tziyon, R. Jacob Meir, and the other outstanding Sephardic rabbis who worked with him.

It is noteworthy that Goldstein’s rebbe, R. Hayyim Eleazar Shapira, also had some negative things to say about Sephardim. In his discussion about the apparently Sabbatean work Hemdat Yamim, R. Shapira refers to R. Hayyim Palache who in his Kol ha-Hayyim[15] defends the Hemdat Yamim, even if the author was a Sabbatian. As R. Palache states, Rabbi Akiva made a mistake in thinking that Bar Kokhba was the Messiah, but this does not disqualify the Torah teachings of R. Akiva. Similarly, we should not disqualify the Hemdat Yamim no matter what the author believed about Shabbetai Zvi. R. Shapira thinks that this is nonsense, and it is obvious to him that if the author of Hemdat Yamim was a Sabbbatian then the work must be shunned.

What angers R. Shapira even more is that R. Palache later states (Kol ha-Hayyim, p. 18a) that there is a tradition not to speak at all about the Shabbetai Zvi episode, not even in a negative way[16]:

וכבר יש קבלה מרבותינו ואבותינו הקדושים שלא לדבר מטוב ועד רע על ענין ש"ץ כי גם קוב לא תקבנו גם ברך לא תברכנו

R. Shapira finds this outrageous, since how can one not speak negatively about such an evil person as Shabbetai Zvi. He writes:[17]

ורחמנא לישזבן מהאי דעתא הנפסדת המטלת ספיקות מעין היש ה'בקרבנו וכו'והיתכן כי על משיח השקר שהמיר דתו למחמדנות באונס או ברצון ועכ"פ שהסית והדיח אלפים מישראל עליו כתוב "גם קוב לא תקבנו"ובודאי בע"כ שהטיל ספיקות אולי הי'אמת ע"כ קוב לא תקבנו לרעה. לא יאומן כי יסופר שיהי'כזה נדפס מרב מגדולי הספרדים לולי ראיתי בעיני – אוי לנו שכך עלתה בימנו שהפרוץ מרובה. ואולי [צ"ל ואילו] הי'כזה נדפס בדור הקדום היו גדולי הדור מרעישים עולם.

After these harsh words, R. Shapira offers his explanation of how R. Palache could have written what he did, and it is perhaps the all-time greatest put-down of Sephardim in rabbinic literature. While R. Shapira has great respect for the Sephardim of earlier generations, and also for special individuals such as R. Alfandari,[18] he thinks that most Sephardim of recent years are simply not that smart, and are thus able to believe all sorts of nonsense.

וחשבתי להצדיק קצת את הה"ג ז"ל בע"ס כל החיים להיות הספרדים בימינו בטבעם רובם נמוכי השכל נוחין להתפתות ולהאמין לכל דבר ע"כ השיאם עון אשמה גם לגדוליהם רבניהם בספיקות כאלה.

What R. Shapira did not know is that this strategy of not speaking bad about Shabbetai Zvi had nothing to do with being sympathetic to him, and was certainly not an example of Sephardic stupidity. Rather, as Gershom Scholem notes, it was a strategy chosen by the rabbis in order to allow the community to return to normal.

In choosing this course, the rabbis of Constantinople and Smyrna may have attempted the impossible; at any rate they acted in what seemed to them the most reasonable and responsible fashion. . . . The messianic propaganda, which had not been checked by either the rabbis or the lay leaders, had roused their emotions and faith to such a pitch that rational criticism and appeals to traditional standards would probably have availed little. It seemed safer and wiser to ignore the whole matter as far as possible, and to let time and oblivion heal the wound. Neither condemnation nor apologies, but silence alone would enable the disturbed community to find the way back to normal life.[19]

Scholem quotes the passage from R. Palache cited above, and he also summarizes another passage from the very same section in R. Palache’s Kol ha-Hayyim.

The earlier version of the story was that R. Sabbatai Ventura of Sofia had shown disrespect at Nathan’s tomb, whereupon his hand dried up and remained paralyzed until he returned again to the tomb and prayed for forgiveness. When his son Abraham Ventura passed through the city on his travels on behalf of the community of Safed, “a drop fell on him during his first night there and he died . . . and was buried next to the tomb of R. Nathan.” (The story is told by R. Hayyim Palache of Smyrna in Kol ha-Hayyim [Smyrna, 1874], pp. 17-18.)[20]

In the earlier Hebrew version of Scholem’s work, Shabbetai Tzvi (Jerusalem, 1957), vol. 2, p. 794 n. 2, the direct quotation of R. Palache is a little different:

"נפל עליו טיפה בלילה ראשונה שנכנס שם וימת שם אברהם וקברוהו סמוך ממש לקברו"של ר'נתן, כפי שסופר בס'כל החיים לר'חיים פאלאג'י מאיזמיר, דפים יז, יח.

Notice how in the Hebrew quotation from R. Palache there is no mention of “R. Nathan” (of Gaza). In other words, the English version is mistaken in including the words “R. Nathan” as part of the direct quote.

Most people who examine the matter will probably also assume that Scholem’s Hebrew text is mistaken, since the story R. Palache tells (which appears on p. 18a, not pp. 17-18 as mentioned by Scholem), has nothing to do with Nathan of Gaza and thus the latter should not have been mentioned by Scholem. As you can see from the page following this paragraph (from Kol ha-Hayyim 18a), R. Palache’s story is about the grave of the anonymous author of Hemdat Yamim, not Nathan of Gaza. (Scholem himself did not regard Nathan of Gaza as the author of Hemdat Yamim.[21])

![]()

What is going on here? Can we assume that a careful scholar like Scholem made such a blunder and inserted Nathan of Gaza into a story that has nothing to do with him? The answer is no, and let me explain what is behind what Scholem writes since for some inexplicable reason he doesn’t do it himself. In Mekhkerei Shabtaut (Tel Aviv, 1991), p. 251, Scholem notes that once R. Jacob Emden (mistakenly) identified Nathan of Gaza as the author of Hemdat Yamim,[22] most Ashkenazic scholars kept away from the book. However, the Sephardic scholars had a different view, and they continued to treasure Hemdat Yamim despite the fact that they regarded Nathan of Gaza as its author. Furthermore, they began to refer to Nathan of Gaza as הרב חמדת ימים.

What is going on here? Can we assume that a careful scholar like Scholem made such a blunder and inserted Nathan of Gaza into a story that has nothing to do with him? The answer is no, and let me explain what is behind what Scholem writes since for some inexplicable reason he doesn’t do it himself. In Mekhkerei Shabtaut (Tel Aviv, 1991), p. 251, Scholem notes that once R. Jacob Emden (mistakenly) identified Nathan of Gaza as the author of Hemdat Yamim,[22] most Ashkenazic scholars kept away from the book. However, the Sephardic scholars had a different view, and they continued to treasure Hemdat Yamim despite the fact that they regarded Nathan of Gaza as its author. Furthermore, they began to refer to Nathan of Gaza as הרב חמדת ימים.

So let us now look again at the passage from R. Palache. It mentions that R. Shabbetai Ventura visited the city of איסקופייא where the grave of הרב חמדת ימים is found. איסקופייא is none other than Skoplje in Macedonia, and this is where Nathan of Gaza died and was buried. In other words, when the story speaks about visiting the grave of הרב חמדת ימים it is referring to visiting the grave of Nathan of Gaza. In Kol ha-Hayyim, p. 17b, R. Palache states that we don’t know who wrote Hemdat Yamim, so it seems that he was passing on a tradition the significance of which even he did not grasp. (If my assumption is correct that R. Palache did not realize that the story he told was referring to visiting the grave of Nathan of Gaza, then he must have assumed that while his generation did not know who the author of Hemdat Yamim was, earlier generations did know, and even knew where his grave was.) What Scholem writes in Sabbatai Sevi about the grave of Nathan of Gaza and Rabbi Shabbetai Ventura and his son Abraham is incomprehensible without the explanation just given, and I have no idea why Scholem did not feel it necessary to provide it himself.

Returning to the comments of R. Hayyim Eleazar Shapira, I wonder what he would have said about the Ashkenazi R. Joseph Seliger who commented that it really doesn’t matter whether R. Jonathan Eybeschuetz believed in Shabbetai Zvi, and our respect for him would not be lessened by such an error.[23]

בדבר המחלקת שבין הגאונים ר'יונתן ור'יעקב עמדן כבר עשה העם כלו פשרה בין שני החולקים ששניהם היו חכמי אמת וצדיקים גמורים, אלא שר'יונתן ז"ל היה נוח ועלוב וענו תלמידו של הלל. ולכן עלה גם בחכמה וגם במעשה מאיש ריבו הקנא והקפדן של שמאי. נושא המחלקת היה נכבד רק בשעתו, בעת אשר פשתה האלילות של ש"ץ וכמעט גמרה לבלע את כל ישראל ותורתו בהבליה ובקסמיה. היום הנה שאלה קלת ערך אם האמין ר'יונתן בש"ץ או לא . . . לו האמין ר'יונתן באמת בש"ץ, אין הטעות החלקית הזאת גדולה מהטעות הכללית להאמין בקמעות. ואם בכל זה כבוד ר'יונתן במקומו מונח לפי מצב הדעות בזמנו, כי לא כל חכמי ישראל זוכים לאמונה צרופה כבן מימון, לא היה ר'יונתן נופל בעינינו אף לו האמין בנביא השקר כר"ח בנבנשתי ז"ל. אבל באמת לא היתה בר'יונתן האמונה הזאת לא ממנה ולא מקצתה.

Due to what R. Shapira said about Sephardim, R. Ovadiah Yosef was very unhappy with him. The following passage, from 24 Sivan, 5767, appears in R. Eliyahu Sheetrit’s Rabbenu.[24] This book is quite fascinating as it is a diary that Sheetrit kept during the years he learnt with R. Ovadiah and assisted him in publishing his books. Most significantly, only a few of the published texts of the diary have been censored.

רבנו כתב על החמדת ימים, ואז ראה בספר חמשה מאמרות של אחד מגאוני הדור הקודם שכתב בצורה לא יפה על הרבנים הספרדים ועל הספרדים בכלל, וגם נזכר במה שבזמנו אמר הגאון הנ"ל על הספרדים "צפרדעים", וביקש ממני לעבור בספר, ובכל מקום שכתוב שמו של הגאון הנ"ל למחוק את המלה "הגאון". עוד אמר רבנו, שהגאון הנ"ל ביקר אצל הגאון מהרש"א אלפנדארי, ושלשה ימים לאחר מכן, נפטר מהרש"א אלפנדארי (ואמר רבנו, שכנראה הגאון הנ"ל עשה עליו עין הרע).

It would be interesting to check if indeed R. Ovadiah’s books published after 2007 are missing the title הגאון before R. Shapira’s name. In the introduction to Hazon Ovadiah: Arba Ta’aniyot, published in 2007, R. Ovadiah refers to R. Shapira’s comments and indeed in this source not only is there no הגאון before his name, but R. Shapira also doesn’t get the less exalted הרה"ג, and he is left with just a ר'. As for what R. Ovadiah said about R. Shapira apparently unintentionally causing the death of R. Alfandari, this will obviously be a great insult to all Munkatcher hasidim.

It must also be noted that R. Ovadiah did not remember correctly, as it was not R. Shapira who referred to the Sephardim as צפרדעים but his follower Moses Goldstein.

R. Chaim Amsalem took note of R. Shapira’s comments about Sephardim and he too was quite offended, and placed these comments in the context of continuing discrimination against Sephardim by the Ashkenazic haredim. He writes as follows (adding a heavy dose Sephardic pride at the end):[25]

מה אני יכול לומר על דברים מעליבים ופוגעים שכאלו "בטבעם רובם נמוכי שכל", אני רק יכול להודות לו שגלה דעתו האמיתית מה הוא חושב הוא ואחרים שכמותו, וא"כ אין פלא על יחס השחצנות והגזענות שהם מגלים כלפי הספרדים, שרי ליה מאריה, וכמה ראוי לו לבקש מחילה קודם כל ממושא הערצתו הגאון מהרש"א אלפאנדרי זצ"ל, הדברים כ"כ נמוכי שכל שאינני רוצה להגרר להעלבות וכדומה, דבריו מדברים בעד עצמם, אבל עוד יבואו ימים שכולם יאכלו מכף ידינו . . .

I am aware of another place where R. Shapira speaks negatively about a great Sephardic sage, R. Hiyya Pontremoli, author of the halakhic work Tzapihit bi-Devash. In Minhat Eleazar, vol. 4, no. 45 (p. 37a), R. Shapira writes as follows:

הנה עשה א"ע כאלו לא ידע או העלים בכונה סוף דברי רש"י . . . וכבר תמהתי עליו איך שכח או במזיד הביא להיפך ממ"ש במאירי

Simply put, he is accusing R. Pontremoli of intellectual dishonesty. R. Ovadiah Yosef[26] calls attention to the second part of the quotation just given, and expresses his great distress that R. Shapira spoke this way about R. Pontremoli.

ואנכי איש צעיר נוראות נפלאתי עליו הפלא ופלא, מפני היד שנשתלחה, לחשוד רב גדול כהגאון בעל צפיחית בדבש, ששכח או הזיד ח"ו בדברי המאירי. הס כי לא להזכיר.

In Abir ha-Ro’im, the recent biography of R. Ovadiah by his grandson, R. Yaakov Sasson, the latter also gives examples of Ashkenazic scholars belittling Sephardic gedolim.[27] The instances Sasson cites should not be understood as conscious belittling. It is just that in these cases the Ashkenazic scholars, not knowing anything about the Sephardic Torah greats, did not take them very seriously. One of Sasson’s examples comes from Iggerot Moshe, Hoshen Mishpat, vol. 2, no. 69 (p. 298), which is R. Moshe Feinstein’s famous responsum on abortion. Here R. Moshe writes:

ופלא שראיתי בספר רב פעלים לחכם ספרדי

Sasson is correct that this is not the most respectful way to refer to R. Joseph Hayyim. R. Moshe continues by rejecting R. Joseph Hayyim’s view and does not pay him much regard. It is because of this that R. Eliezer Waldenberg, in his response to R. Moshe, says as follows after expressing his surprise with the way R. Moshe deals with R. Joseph Hayyim:[28]

ושרי ליה מריה בזה

I would like to know, did R. Moshe even have any idea who R. Joseph Hayyim was? Someone obviously showed R. Moshe the responsum in Rav Pealim, but was it explained to R. Moshe that the author of Rav Pealim is the Ben Ish Hai, and that for many Sephardim R. Joseph Hayyim’s significance is the equivalent of what the Hafetz Hayyim is for Ashkenazim, i.e., a towering figure, both spiritually and halakhically? Did R. Moshe even know the name of the man who wrote Rav Pealim, since if he only had a copy of the responsum he wouldn’t see the author’s name, as there is no name given at the end of the various teshuvot?

It is possible that the answer to one or more of these questions is “no”, and R. Moshe therefore related to R. Joseph Hayyim the same way he related to other scholars, Sephardic and Ashkenazic, whom he did not view as top-of-the-line poskim. In the last paragraph of his responsum, when dealing with R. Eliezer Waldenberg, here too R. Moshe does not show great respect but simply refers to R. Waldenberg as .חכם אחד. Contrast this with how in this responsum R. Moshe refers to R. Hayyim Ozer Grodzinksi, R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, and R. Isser Yehudah Unterman.

Leaving aside what I have just mentioned, R. Moshe’s responsum does have some problematic elements. R. David Feldman even claimed that it was not written by R. Moshe! Here is his letter that appears in Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 20, no. 56.

![]()

This is a very strange claim, as the responsum first appeared in 1978 in the Sefer ha-Zikaron for R. Yehezkel Abramsky. Are we supposed to believe that a responsum that appeared in R. Moshe’s lifetime was not written by him? This is clearly impossible. (When I made this point to R. Feldman he continued to insist that R. Moshe did not write the responsum.) Yet as I mentioned, there are indeed some problematic things in this responsum. For example, what is one to make of the following sentence in which R. Moshe attacks a point in R. Eliezer Waldenberg’s first responsum on abortion?[29]

וגם כתב שהשאילת יעב"ץ מתיר אף שאסר בפירוש, בשביל לשון וגם בעובר כשר יש צד להקל לצורך גדול, אף שברור ופשוט שלשון יש צד להקל הוא כאמר שיותר צדדים איכא לאסור.

R. Waldenberg states that it is “ridiculous” to claim that when R. Jacob Emden writes יש צד להקל that it really means that it is forbidden.[30] We, of course, would never use such language about something R. Moshe wrote, but the question remains, could R. Moshe really have believed that יש צד להקל means שיותר צדדים איכא לאסור?

R. Moshe Maimon wrote to me as follows:

As for the question of יש צד להקל – I think all R. Moshe meant is that when a posek says יש צד להקל he is conceding that the presumption is that it should really be אסור but nevertheless sees some ground for a קולא. To R. Moshe this indicates that this posek is more inclined to the צד איסור and can be counted on as a סניף supportive of a more stringent view.[31]

An alternative perspective is offered by a Lakewood scholar who wrote to me: “R. Moshe may have vehemently disagreed with the יעב"ץ but preferred to twist the meaning rather than say openly that the יעב"ץ was mistaken, a very typical thing for someone like R. Moshe to do.” I responded that I don’t find this compelling, since in the second to last paragraph of his responsum R. Moshe has no problem stating that Emden is mistaken, so why would he write differently in the last paragraph?

The Lakewood scholar replied as follows:

If it was a sensitive issue (I'm guessing) R. Moshe may have wanted to strip the opposing view of any legitimacy by insisting that the יעב״ץ didn't mean it. It's almost like saying he couldn't have meant it. Regarding the general approach of twisting the words of achronim in order make it consistent with your own view: The Mekor Baruch describes a similar approach that he attributes to Rabbi Chaim Volozhin, that although one may rule against the Shulchan Aruch, one should nonetheless seek to find hairsplitting differences between your ruling and the Shulchan Aruch’s so not to appear as if you are going head on. The Chazon Ish would say that a טעות סופר נפלה rather than say a rishon made a mistake.

Similar to what the Lakewood scholar claimed, R. Chaim Rapoport, who has published a good deal on the Iggerot Moshe, wrote to me as follows:

מ"ש הגרמ"פ שם "שברור ופשוט שלשון יש צד להקל הוא כאמר שיותר צדדים איכא לאסור" [שיש שתמהו על זה], הנה לפענ"ד הדבר מתאים מאד לדרכו של הגרמ"פ כשהוא משוכנע לחלוטין בצדקת שיטתו ובשלילת השיטה החולקת, ובכה"ג הרגיש בעצמו שמוכרח הוא לקרב את הרחוקים בזרוע, כדי לקיים את מה שהי'ברור בעיניו כשמש בצהריים.

ובאמת, בנידון תשובה זו אין דבריו תמוהים כ"כ, שהרי לפעמים מצינו בדברי הפוסקים שכתבו שיש צד להקל ומ"מ אין להקל למעשה [וע"כ צ"ל דהיינו] בגלל שישנם צדדים אחרים [ואפילו צדדים יותר גדולים] להחמיר. ואם כי בנדו"ד הרי מתוכן דברי היעב"ץ אין נראה כן, מ"מ העמיס הגרמ"פ כוונה זו בדברי היעב"ץ, כי 'ההכרח לא יגונה'.

לזל הגרמ"פ בכבודו של הגרא"י ולדנברג בעל שו"ת ציץ אליעזר, הנה אם כנים הדברים, נראה שהי'זה בגלל שהיטב חרה לו להגרמ"פ ע"ז שפרסם הגרא"י ולדנברג את היתרו להפיל עוברי 'תיי-סקס'– אשר לדעתו הר"ז בגדר שפיכת דמים ממש, ואורייתא הוא דמרתחא בי'.

ומ"ש הרב בעל ציץ אליעזר על הגרמ"פ "ושרי לי'מרי'בזה" [על מה שנראה מלשונו שמיעט בחשיבותו ומעמדו של הרב פעלים] נראה שכתב כן כלפי מה שכתב הגרמ"פ בתשובתו הנ"ל עליו [על הצי"א] "ושרי לי'מרי'בזה", ועד"ז כתב הגרמ"פ בתשובתו (שם) על היעב"ץ, וע"ד מה שאחז"ל מדויל ידי'משתלים.

Finally, returning to the matter of negative portrayals of Sephardim, take a look at this bizarre passage in Israel Abraham’s classic Jewish Life in the Middle Ages, p. 122.

There was less warmth in the Oriental Jewish home, less of that tenderness which was once a common characteristic of Jews all the world over, but came in process of time to distinguish Western Jews from their gayer but more shallow brethren of the East. One seems to detect a feebler sense of responsibility in the mental attitude of an Oriental father to his offspring, just as one detects more volubility but less intensity in the Oriental Jew’s prayers.

3. For those who are interested, on Saturday night November 7 at 8pm, I will be speaking at Congregation Ohr Torah, 48 Edgemount Road, Edison, N.J. The title of the talk is “Some Unusual Orthodox Responses to the Rise of Nazism.”

[1] He also refers to himself this way in Birat Migdal Oz two pages later, which is mistakenly numbered as 135a. See also Torat ha-Kenaot (Lvov, 1870), p. 54, where he writes: ונמסר לי הסריס.

[2] Va’ad le-Hakhamim (Lublin, 1881), p. 3a.

[3] Ibid., p. 3b.

[4] Ibid., p. 4a.

[5] See R. Meir Mazuz, Emet Keneh (Bnei Brak, 2000), p. 227. R. Mazuz knows that Emden referred to himself as השכוי, but I can't tell if he is aware that Emden also referred to himself as .שלו I say this since R. Mazuz mentions the gematria of שלו without indicating that Emden ever used the word. He then makes the connection to ולחם שמים ישביעם.

In 1756 the book Shevirat Luhot ha-Aven appeared. The title page says Zolkiew but this is probably intended to cover up its real place of publication, Altona. According to the haskamah, written by R. Abraham of Zamocz, the author is דוד אוז, an otherwise unknown person. There is no doubt, however, that this book was written by Emden. R. Menahem Mendel Goldstein even found a gematria to tie this name to Emden. See Etz Hayyim 15 (Tamuz-Av, 5771), p. 235 n. 46:

דו"ד או"ז עם ב'הכוללים בגי'יעק"ב ב"ן צב"י במספר קטן

[6] The image is from here. This site mistakenly explains that “The kneeling figure represents the Sanhedrin.”

[7] Technically, the word should be pronounced vetikin, with a sheva under the vav, but no one does this.

[8] See Ovadiah Hen, Ha-Ketav ve-ha-Mikhtav (Bnei Brak, 2014), p. 89. See also Ben Yehudah's dictionary which does not list any early sources in which vatik means old. However, Michael Sokoloff, A Dictionary of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic of the Talmudic and Geonic Periods (Ramat Gan, 2002), p. 396, gives "old" as a translation for ותיק, referring to its use in an incantation bowl.

[9] “Le-Ferush ha-Munahim ‘Vetikin’, ‘Vatik’, ve’Talmid Vatik’ be-Sefer Ben Sira u-va-Sifrut ha-Talmudit,” Sidra 13 (1997), pp. 47-60.

[10] Maimon and pretty much everyone else transliterate the title as Masaot Yerushalayim. I believe this to be mistaken. מסעות in the title is a construct, and is the same thing as מסעי. There should be a sheva under the samekh, not a kamatz. See here.

[11] See his Va-Yomer Meir, vol. 1, no. 10.

[12] For the origin of the notion that R. Shimon Ben Yohai died on Lag ba-Omer, see Eliezer Brodt’s post here.

[13] This letter originally appeared in Vaknin, Va-Yomer Meir,vol. 1, no. 10.

[14] Mas’ot Yerushalayim (2004), p. 258.

[15] Ma’arekhet he, no. 18 (pp. 17ff.).

[16] I am surprised that R. Shapira doesn’t also criticize R. Palache for mentioning the tradition that R. Hayyim Joseph David Azulai was a gilgul of the author of Hemdat Yamim. See Palache, Kol ha-Hayyim, p. 18a.

[17] Hamishah Ma’amarot (Jerusalem, n.d.), p. 157 (Ma’amar Meshiv Mipnei ha-Kavod).

[18] Regarding R. Alfandari, see the first two stories here from Otzrot ha-Sofer 13 (Tishrei 5763), p. 89.

It boggles the mind to think that there are people who are so gullible that they can actually believe that R. Alfandari met the Hatam Sofer in Pressburg.

There are all sorts of legends about great rabbis visiting far-off places and meeting with other great rabbis. Sometimes the stories are chronologically impossible, e.g., the tale of Ibn Ezra visiting Rashi. See Naftali Ben-Menahem, Inyanei Ibn Ezra (Jerusalem, 1978), pp. 356ff. See my Limits of Orthodox Theology, p. 115, about the legend of Maimonides' visit to France. See also Otzar ha-Geonim: Hagigah, p. 16, where we are told of the well known "fact" that R. Natronai Gaon magically came from Babylonia to Spain and then returned home.

There are all sorts of legends about great rabbis visiting far-off places and meeting with other great rabbis. Sometimes the stories are chronologically impossible, e.g., the tale of Ibn Ezra visiting Rashi. See Naftali Ben-Menahem, Inyanei Ibn Ezra (Jerusalem, 1978), pp. 356ff. See my Limits of Orthodox Theology, p. 115, about the legend of Maimonides' visit to France. See also Otzar ha-Geonim: Hagigah, p. 16, where we are told of the well known "fact" that R. Natronai Gaon magically came from Babylonia to Spain and then returned home.

ודבר ברור ומפורסם לאנשי ספרד ומסורת בידם מאבותיהם כי מר רב נטרונאי גאון זצ"ל בקפיצת הדרך בא אליהם מבבל וריבץ תורה וחזר, וכי לא הלך בשיירא ולא נראה בדרך

[19] Gershom Scholem, Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah, trans. R. J. Zwi Werblowsky (Princeton, 1973), pp. 698-699.

[20] Scholem, Sabbatai Sevi, p. 926 n. 270.

[21] See Scholem, Mehkerei Shabtaut (Tel Aviv, 1991), p. 251.

[22] See Avraham Ya’ari, Ta’alumat Sefer (Jerusalem, 1954), p. 10.

[23] Kitvei ha-Rav Dr. Yosef ha-Levi Seliger (Jerusalem, 1930), p. 503. The last section of this book, where the quoted comment appears, has been deleted (censored?) on Otzar ha-Hokhmah. It can be found in full on hebrewbooks.org.

[24] (Jerusalem, 2014), p. 378.

[25] Gadol ha-Neheneh mi-Yegio (n.p., 2012), pp. 93-94. The three periods at the end of the quotation appear in the original.

[26] Yabia Omer, vol. 2, Orah Hayyim, no. 18.

[27] See Abir ha-Ro’im, vol. 2, p. 134.

[28] Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 14, p. 186.

[29] Iggerot Moshe, Hoshen Mishpat 2, p. 300.

[30] Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 14, p. 186.

ומגוחח {צ"ל ומגוחך] הוא לפרש כוונתו ולומר דלשון יש צד להקל הוא כאומר שיותר צדדים איכא לאיסור

[31] Somewhat parallel to this is R. Yair Hayyim Bacharach’s view that when R. Moses Isserles write ויש מחמירין it actually means that he doesn’t accept the stringency, since if he did he would have written .ויש אוסרין See Havot Yair, no. 185.