The Book of Disputes between East and West

or

A Treasury of Alternate Customs from the Land of Israel and from Babylon

Translated and Annotated by Leor Jacobi

Based primarily on the Margulies Edition

Menahem Av, 5772

Jerusalem

After the translation of the text itself, various additional items are added, some of them never before published. Also included is a translated summary of major sections of Margaliot's introduction, along with comments and updates.

Round brackets reflect text found in only certain Hebrew manuscripts as indicated by Margulies in his Hebrew edition.

Square brackets contain English insertions of this translator.

1. People of the East sit while reading the Sh'ma. The residents of the Land of Israel stand.

2. People of the East do not mourn for a baby [who has died] unless he has reached 30 days [of life]. The residents of the Land of Israel [mourn] even if he is only a day old. (He is like a fully-grown groom [=man])

3. People of the East will allow a nursing mother to marry within twenty-four months of the death of her baby. Residents of the Land of Israel require her to wait twenty-four months, lest she come to kill her son.

4. People of the East redeem the firstborn with twenty-eight (and a half) royal pieces of silver. Residents of the Land of Israel use five shekels, which are equivalent to seven (and a third) royal pieces of silver.

5. People of the East exempt a mourner [from observing laws and customs of mourning, if the relation expired just] before a festival, even a moment [before]. Residents of the Land of Israel only exempt a mourner from the decree of seven days [of mourning] if at least three days have elapsed before the festival.

6. People of the East forbid a bride from [having relations with] her husband for the full seven [days] for she is considered to be a menstruating as a result of the relations. The residents of the Land of Israel (say) that since his removing of her hymen is painful [it is an external wound and] she is permitted immediately.

7. The marriage contract of the People of the East consists of twenty-five pieces of silver (and their dowry). The residents of the Land of Israel (say) that anyone who [obligates himself] to less than two hundred for a maiden or one hundred for a widow, is effecting a promiscuous relationship.

8. People of the East permit [the use of] an oven (during Passover), based on the source: “[We may] roll the Passover [lamb] in the oven at sundown.” (Mishnah Shabbat 1:11) Residents of the Land of Israel (say): “Disregard the Passover [lamb] since it is a sacrifice, and we [even] desecrate the Sabbath on account of it.”

9. People of the East do not wash [= ritual immersion] after experiencing a seminal emission or after relations (since they reason that “we are in an impure land”). Residents of the Land of Israel (do wash after a seminal emission or relations, and) even on the Day of Atonement (for they maintain that those who have seen emissions should wash in secret on the Sabbath and on the Day of Atonement) as a matter of course, [which they learn] from the example of Rabbi Yosi bar Halafta, who was seen immersing himself on the Day of Atonement.

10. People of the East permit gentile butter [alternatively: cheese], (saying) that it cannot become impure. Residents of the Land of Israel forbid it on account of (three things: because of) milk which was expressed by a gentile (without a Jew observing him, because of gentile cooking) and because of impure fat (which it might be mixed with).

11. People of the East say that a menstruating woman may perform all types of household duties except for three things: mixing drinks, making the bed, and washing his face, hands, and legs. According to the residents of the land of Israel, she may not touch anything moist or household utensils. Only reluctantly was she permitted to even nurse her child.

12. People of the East do not say recite eulogies [alternatively: the prayer “tsidduk ha-din”]in the presence of the dead (during the in-between days of the festival). Residents of the Land of Israel do recite these before him.

13. People of the East do not rip up a divorce contract. Residents of the Land of Israel rip it up. [Acc. to Lewin, this may have originally referred to whether a mourner rips his garment during the intermediate days of a festival.]

14. People of the East have mourners come to the synagogue each day. Residents of the Land of Israel do not allow him to enter, with the sole exception of the Sabbath.

15. People of the East do not clean their posteriors with water. Residents of the Land of Israel do cleanse themselves [with water], (based on the source:) A generation which considers itself pure ... [but has not cleaned itself from its excrement.] (Proverbs 30:12)

16. People of the East [permit one to] weigh meat on intermediate days of the festival. Residents of the Land of Israel forbid hanging it on a scale, even just to keep it away from rodents, (based on the source: “One may not operate a scale at all.” – Mishna Beitza 6, 3)

17. People of the East circumcise [babies] over water and then dab [the water] onto their faces, (from here: “and I will wash you with water, [rinse your blood off of you, and anoint you with oil]” – Ezekiel 16:9) Residents of the Land of Israel circumcise over dust, from here: “Also, due to the blood of your covenant have I sent your prisoners free from a pit with no water in it.” (Zechariah 9:11)

18. People of the East (only) check the lungs. Residents of the Land of Israel (check) eighteen types of disqualifications.

19. People of the East only recite a blessing [= grace after meals] over [a cup of] diluted wine. Residents of the Land of Israel (will recite a blessing) when it is fully potent.

20. When thurmusin [beans] and tree-fruit are served to People of the East simultaneously, they recite the blessing for fruit of the tree and set aside the beans. Residents of the Land of Israel recite a blessing on the thurmusin, since everything is included in “[the fruits of] the earth.”

21. On the Sabbath, people of the East break bread on two loaves, for they expound: “a double portion of bread” (Exodous 16:21) [which fell on the Eve of the Sabbath]. Residents of the Land of Israel break bread exclusively on a single loaf, so that the [lesser] honor of the Eve of the Sabbath will not intrude upon [the honor of] the Sabbath.

22. People of the East spread their hands [= recite the priestly blessing] during fasts and on the on the ninth of Av as part of the evening benedictions. Residents of the Land of Israel only spread their hands during the morning services, with the sole exception of the Day of Atonement.

23. People of the East will not slaughter a newly-born animal until the eighth day. Residents of the Land of Israel will slaughter even a newborn, for [they maintain that] the prohibition of the eighth day applies only to sacrifices.

24. People of the East do mention the word mazon [=nourishment] in the blessings of grace after dining. Residents of the Land of Israel consider mazon to be [the] central [component of the blessings] (for everything else is peripheral to mazon].

25. A ring does not sanctify marriage according to people of the East. Residents of the Land of Israel consider it [sufficient to] fully sanctify a marriage.

26. People of the East individually redeem the second tithe and the planting of the fourth year. Residents of the Land of Israel only redeem them in [the presence of] three [men].

27. The divorce contracts of people of the East contain two ten-letter words ['dytyhwyyyn' and 'ditiṣbyyyn']. Those of the residents of the Land of Israel contain three ten-letter words [the third is not known].

28. People of the East bless the [bride and] groom with seven blessing. Residents of the Land of Israel recite three [blessings, which have been forgotten].

29. According to people of the East, the prayer leader recites the priestly blessing (before the congregation) [in the absence of Kohanim]. Residents of the Land of Israel do not (allow the prayer leader to recite the priestly blessing, for they expound [from the verse]: “So they shall put my name” (Numbers 6:27) that it is strictly forbidden for anyone to “put” the holy name), unless they are Kohanim.

30. People of the East forbid bread baked by a gentile, but will consume gentile bread if a Jew threw a piece of wood into the fire. Residents of the Land of Israel forbid it (even with the wood, for the wood neither forbids nor permits. When are they lenient? In cases when there is nothing [else] to eat, and already a day or two have passed without consuming anything. It was thus permitted to revive his soul so that his soul should be maintained, but only from a [gentile] baker who has never brought meat into his bakery, even though it considered a [separate] cooked dish.)

31. People of the East carry coins from place to place on the Sabbath. Residents of the Land of Israel (say) that it is forbidden to even touch them. Why? Because all types of work are done with them.

32. People of the East recite: “meqadesh ha-shabbat,” [who sanctifies the Sabbath]. Residents of the Land of Israel recite: “meqadesh Yisrael v’yom ha-shabbat” [who sanctifies Israel and the Sabbath day].

33. Among people of the East, a disciple does not greet his master with: “shalom”. Among residents of the Land of Israel a disciple greets his master [by saying]: “shalomunto you, rabbi.”

34. According to People of the East, if a yevama [=a woman automatically betrothed to the brother of her deceased husband] should marry [another man] without halitza [=a legal procedure which frees her from this betrothal] and her yavam [=the brother] should return from overseas, he performs the halitza (to her) and she remains with her (second) husband. Residents of the Land of Israel remove [=forbid] her from both of them.

35. People of the East exempt a yevamafrom halitza [only] once the baby is thirty days old. According to residents of the Land of Israel, even if only the head and most of the body emerged alive, and even for only a moment (before the father died), she is fully exempt from halitza and from yivum [and may remarry freely], (for they expound: “If he has left seed, she is exempt.”)

36. People of the East turn their faces (towards the congregation) and their backs towards the aron[=closet containing the Torah scroll]. Residents of the Land of Israel [are positioned with] their faces towards the aron.

37. According to people of the East, one [scribe] writes the divorce contract and another signs along with the writer. Among residents of the Land of Israel, one writes and two [others] sign.

38. People of the East marry the [bride and] groom on Thursday. Residents of the Land of Israel [marry] on Wednesday, (according to the law: “a maiden marries on Wednesday.” – Mishnah Ketubot 1:1)

39. People of the East perform labors on the intermediate days of the festivals. Residents of the Land of Israel do not do them at all. Rather, they eat and drink and exert their [energies in learning] Torah, (for the sages have taught that: “it is forbidden to perform labors on the intermediate days of the festivals.”)

40. People of the East begin [the initial act of] intercourse with genital insertion in the natural manner. Residents of the Land of Israel use a finger [to break the hymen and enable conception through the first act of intercourse. Alternatively, to verify virginity.]

41. People of the East observe two festival days. Residents of the Land of Israel observe one, (as per the commandment of the Torah.)

42. People of the East forbid the Kohanim from blessing the congregation if they have long, unkempt hair. [Alternatively: with their heads uncovered]. Among residents of the Land of Israel Kohanim do () [in fact bless the congregation with long, unkempt hair.]

43. People of the East whisper the eighteen benedictions while praying. Residents of the Land of Israel [pray] out loud, in order that people should become familiar with them.

44. People of the East count the Omeronly at night. Residents of the Land of Israel count during the day and at night.

45. People of the East circumcise with a razor. Residents of the Land of Israel use a knife.

46. (People of the East mix a remedy for circumcision from donkey dung and cumin. The residents of the Land of Israel do not do this.)

47. According to people of the East, the prayer leader and the congregation read the weekly [Torah] portion [of the annual cycle] together. Among residents of the Land of Israel, the congregation reads the weekly portion and the prayer leader [reads] the weekly [triennial] orders.

48. People of the East celebrate Simhat Torah [the festival of the completion of the Pentateuch] every year. Residents of the Land of Israel celebrate it once every three-and-a-half years.

49. People of the East bless the Torah while it is being [re-]inserted [into the Aron]. Residents of the Land of Israel bless both while it is being inserted and while being removed, (according to scripture and law, as per the verse: “and upon its opening the entire nation stood.” – Nehemia 8:5)

50. (According to people of the East, a Kohen may not bless the congregation until he has married. Residents of the Land of Israel [allow him to] bless even before he has married a woman.)

51. People of the East do not carry a palm branch [when the first day of the festival of Tabernacles falls] on the Sabbath. Rather they take a myrtle branch. Residents of the Land of Israel (carry both the palm and the myrtle on the first day of the festival which falls on the Sabbath, according to the verse:) “And you should take for yourselves” (Leviticus 23:40) [which is expounded to include:] “on the Sabbath.” (Bavli Sukkah 43a)

52. (Residents of the Land of Israel permit the consumption of daytra fats. Residents of Babylon forbid it.)

53. People of the East permit [the consumption of] broad beans which a gentile has boiled, and also locusts. Residents of the Land of Israel forbid it, (since they mix their boiled meat with their boiled fruits [= produce].)

54. People of the East do not blow sirens before the onset of the Sabbath. Residents of the Land of Israel sound three sirens.

55. According to people of the East, Kohanim lift their hands [to bless the people] three times on the Day of Atonement. Residents of the Land of Israel [bless] four times on that day: shaharit, musaf, minha, and neila.

56. (*). Residents of Babylon permit [the consumption of] milk [from a cow] which a gentile has milked, [even] without a Jew having watched him, provided that there are no unclean animals in his flock. Residents of the Land of Israel forbid its’ consumption. (This item is found in only one manuscript. Thus, Margulies doubts whether it is included in the original collection; however, he maintains that it is historically authentic and thus included it in the commentary section.)

Margulies' running commentary has not been translated.

[Translator's note on additional items:

There are four different types of items and it is important to distinguish between them.

A. Items which appear in multiple versions of the Geonic list collections, the main body of the present work.

B. Items which appear to have been added to certain manuscript versions of the list after its “publication,” during the Geonic period or shortly thereafter. This includes items 46, 50, and 56, and possibly others. Since they may actually be remnants of the original list and do appear in the manuscripts, Margulies and Lewin did include them in attempting to produce a critical version of this text itself. [Elkin's 1998 Tarbiz article hints that the original work may have been smaller than Margulies supposed and hence more of the text translated above would fall into this category.]

C. Items which are culled from external Geonic literature and provide direct testimonial evidence for the historical validity of these distinctions. They could conceivably have been included in the original list, but for one reason or another were not. This describes Lewin's additions, and the first section of Miller's additions.

D. Items which were deduced from prior Talmudic literature. Kaftor w'Ferah seems to have pioneered this field, picked up and extended by Miller and others. It should be noted that these items should all be evaluated separately, as they do not necessarily constitute testimonial evidence and rather, in some cases, may be merely theoretical.]

Additional items collected by R. Yoel HaKohen Miller (1878)

From Masekhet Sofrim:

56. People of the East recite kaddish and borkhuwith ten men. People of the Land of Israel [recite] with seven (10:7)

57. People of the East respond “Steadfast are you” after the reading of the prophets while sitting. Residents of the Land of Israel [respond] while standing. (13:10)

58. People of the East fast before Purim. People of the Land of Israel [fast] after Purim, based on Nikanor. (17:4, from Tosefta)

59. People of the East recite Kedusha each day. People of the Land of Israel only recite it on the Sabbath and Festival days. (Tosafot Sanhedrin 37b ad. Loc. Mknp, citing Geonim

Compiled by Miller from Kaftor w'Ferah of Rabbi Ashtori HaParḥi (Isaac HaKohen ben Moses, 1280-1366), deduced from talmudic sources:

60. People of the East do not ordain judges. People of the Land of Israel do ordain. (Sanhedrin Chapter 1)

61. People of the East conclude [the threefold benediction]: “for the land and the fruit.” People of the Land of Israel [conclude]: “for the land and its fruit” (Berakhot, 6th chapter)

62. People of the East first plow and then sow seeds. People of the Land of Israel first sow and then plow. (Sabbath, 7th chapter)

63. People of the East do not chase after idol worship [in order to destroy it]. People of the Land of Israel do chase after it. (Sifre Devarim Re'eh 61)

64. People of the East do not collect fines. People of the Land of Israel do collect in court. (end of Ketuvot ch. 3...)

65. People of the East permit a brown citron [for use among the four species]. People of the Land of Israel forbid it. (Sukkah, ch. 3)

66. People of the East grind with a small mortar on a festival day. People of the Land of Israel forbid it (Beitza, ch. 1)

67. People of the East [formally] begin the meal [and apply its laws] once the belt has been released. People of the Land of Israel [begin] once the hands have been washed. (Shabbat, ch. 1)

68. People of the East maintain that one who purchases a slave from a gentile, who does not wish to become circumcised [immediately], may postpone and continue deliberations up to twelve months. People of the Land of Israel do not allow any delay lest sanctified food become defiled through contact with him. (Yevamot 48b)

69. People of the East do not transfer bones of the dead from little caves to small holes in caves [where presumably whole cadavers could not fit,] in order to bury other dead. People of the Land of Israel do transfer [bones]. (Rav Hai Gaon, as cited by Ramban, in Torat ha-adam)

70. People of the East first marry and then learn Torah. People of the Land of Israel learn Torah first and then marry. (Kiddushin 29b)

71. People of the East recite nineteen blessings. People of the Land of Israel recite eighteen blessings. (Rabbenu Yeshaya ha-Zaqen, RID, in his commentary to Ta'anit, cited here)

72. People of the East do not mention “dew” during the summer. People of the Land of Israel do mention it. (PT Ta'anit ch. 1, Berakhot ch. 5)

73. People of the East are not concerned with “pairs.” People of the Land of Israel are concerned. (Pesahim 110) [in all manuscript and printed versions of the Talmud known to me it appears in reverse and was apparently copied by mistake here.]

I would now like to present some very special additions of Rabbi Benjamin Wolf Singer (1855-1930). R. Daniel Sperber published a volume of his hiddushim/novella. See his biography of the author here and here. Much more about him later. I hope to devote a future post to Rabbi Singer and his brother.

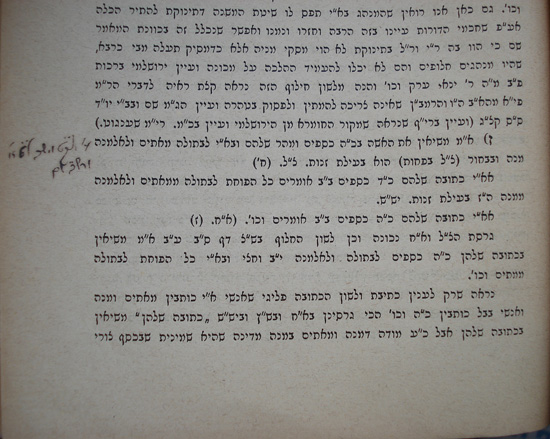

These notes have never before been published, and were found in the form of his handwritten notes in the back of his personal copy of Miller's edition of the work, now housed in the Bar Ilan University central library. The notes follow the extra hiluqim of Kaftor v'Ferah, ShIR, and Miller which we have just translated above. Apparently, they inspired Rabbi Singer to continue their work on the very same page! His notes look like this:

(Click for large, high-resolution images)

What follows is the best I could do for a transcription. All of the main points are clear, but not all of the references. Even this I couldn't have done without a lot of assistance from my friend R. Yehezkel Druk, who is responsible in no small part for the many corrections and additions in Moreshet L'Hanhil's volumes of the new Friedman Shulhan Arukh.

Hopefully, some of the readers viewing at home can decipher some more of this. If you can, please comment! A translation and more follows.

תוספות חלופי מנהגים של ר' בנימין זאב זינגער

א. מחלמ"נ [=מחלפי מנהגים?] דבבבל לא קפדו אטבילת קרי עיין ברכות כ"ב. ובא"י קפדו. ע' ירושלמי שם פ"ג ה"ב, תמן נהגין כו' ע"ש.

ב. בבבל שובתין מתוך מריעין, שבת לד: מנהג אבותיהן בידיהן. ע”ש.

ג. בבבל קרו הלל בר"ח ובא"י לא. תענית כח: מנהג אבותיהן בידיהן. ע"ש.

ד. בבבל קרו פרסא עי' (חולין) פסחים צג: וצ. ולהיפך בא"י קרו רק ד' מילין. עי' ירושלמי ברכות פ"א ה"א ושם נסמן [וירושלמי שבת סוף פרק קמא עד ד' מיל ועיין יומא כ:] ואותה ?הכחיי? עצמה דרבי יהודה דאיתא בפסחים פרסא היא בירושלמי במילין. והא דבחולין קכב: עד ד' מיל דאמר בשם רבי ינאי ורשל"ק [ריש לקיש] בני ארץ ישראל. ועי' ברכות טו ע"א [אבל לאחוריה אפילו מיל אינו חוזר [ומינה] מיל הוא דאינו חוזר הא פחות ממיל חוזר] סוטה מו: [וכמה א"ר ששת עד פרסה ולא אמרן אלא רבו שאינו מובהק אבל רבו מובהק שלשה פרסאות] סנה' ה: [ותניא תלמיד אל יורה הלכה במקום רבו אלא אם כן היה רחוק ממנו שלש פרסאות כנגד מחנה ישראל] סוכה מד: [אמר אייבו משום רבי אלעזר בר צדוק אל יהלך אדם בערבי שבתות יותר משלש פרסאות] ושם נראה דראב"ץ [=רבי אלעזר בר צדוק] בבלי היה מדאמר בלשון פרסי ועי' תו'[ספתא] ב"ק פ"ח מ"ט [אין פורסין נשבין ליונין אלא אם כן היה רחוק מן היישוב שלשים ריס] ל' ריס (והיינו ד' פרסי) ועי' נדה כד: תניא אבא שאול אומר ואי תימא רבי יוחנן כו' ורצתי אחריו ג' פרסאות

ה. לדעת בני א"י ד' מפתחות ביד הקב"ו ולדעת הבבלי ג' עיין ריש תענית ומאיר עיני חכמים דף מב: וכיוצא בזה ברכו' ג' ע"ב רבי אומר ד' משמרות רבי נתן ג' ונראה שבא"י קיימו מספר ד' ובבל ג'

ו. ירושלמי פ"ק דראש השנה תמן חשן [תמן חשין לצומא רבה תרין יומין] ? יומא רבה ב' יומי' ועי' סה"ד [סוף הלכה ד'] שאבוה… בשמת ע"י זה [פני משה מסכת ראש השנה פרק א: "תמן חשין לצומא רבא תרין יומין. בבבל היו אנשים שחששו לעשות מספק ב' ימים יה"כ ולהתענות ואמר להן רב חסדא למה לכם להכניס עצמיכם למספק הזה שתוכלו להסתכן מחמת כך הלא חזקה היא שאין הב"ד מתעצלין בו מלשלוח שלוחים להודיע לכל הגולה אם עיברו אלול ואם אין שלוחין באין תסמכו על הרוב שאין אלול מעובר. ומייתי להאי עובדא דאבוה דר' שמואל בר רב יצחק והוא רב יצחק גופיה שחשש ע"ע וצם תרין יומין ואפסק כרוכה ודמיך. כשהפסיק מן התענית ורצה לכרוך ולאכול נתחלש ונפטר. ועל שהכניס עצמו לסכנה מספק לא הזכירו שמו להדיא ואמרו אבוה דר' שמואל בר רב יצחק".]

ז. ירושלמי ברכות פ"ב ה"א כך אינון (בבלאי) נהגין גביהון זעירא לא שאל בשלמיה דרבה

ח. עי' ירושלמי סוכה פ"ד ה"א ושביעית פ"א ה"ז ועיין שם פ"ד ה"א או' רבי יוחנן לרבי חייה בר בא בבלייא תרין מילין סלקון בידיכון מפשיטותא דתעניתא וערובתא דיומא שביעייא. ורבנן דקיסרין אמרין אף הדא מקזתה ועי' בבלי סוכה מד. ??

ט. יוסף בבבלי יוסי בירושלמי עי' ?יבמות? קג ע"א

7. ברכות פ"ח ה"א ירו' אמר אר"י ב"ר נהיגין תמן במקום שאין יין ש"צ עובר לפני התיבה ואומר ברכה אחת מעין שבע וחותם במקדש ישראל ואת יום השבת. ועי' ?רא"ש? ?? י"ב שלא מצאנו כן בבבלי

8. עיין ברכות נ. בבבל נהגי כרבי ישמעאל ברכו א"ה המבורך – וירושלמי פ"ז דברכות ה"ד [נדצ"ל: ה"ג] נראה דבא"י כר"ע

9. ירושלמי ברכות פ"ז ה"ד [נדצ"ל: ה"ג] נראה דבא"י כשקראו כהן במקום לוי לא בירך שנית ובבבל מברך. עיין שם. תוס' גיטין נט: [ד"ה כי קאמרינן באותו כהן, והשווה תוספת לוין סו' י"ג וי"ד]

10. פסחים נו: בענין ברוך שכמל"ו [שם כבוד מלכותו לעולם ועד] דבא"י אומרין אותו בקול רם מפני המינין ובנהרדעא בחשאי שאין שם מינין מב.. לר.. גבי ר' אבהו ב'. [אולי הכוונה לצטט ויכוח של מין עם ר' אבהו.]

Here is a loose translation without the references:

- In Babylon they were lax regarding the requirement for one who experienced seminal emissions [Ba'al Qeri] to immerse himself in a mikva. In the Land of Israel they were stringent.

- In Babylonia they commence the Sabbath in the midst of the blowing of the shofar teru'ah — They retain their fathers’ practice. (Sabbath 35b)

- In Babylon, they read the hallel on the day of the New Moon. In the land of Israel they did not (Ta'anit 28b, “They retain their fathers’ practice”).

- In Babylon [a large unit of length] is referred to as a “parsa.” On the other hand, in the land of Israel, it is referred to as “four mil.” [miles]

- According to the understanding of the sages of the Land of Israel there are four keys in the hands of the holy one, blessed be he. According to the understanding of the sages of Babylon, there are three.

- In Babylon there were sages who fasted two Days of Atonement due to uncertainty as to on which day the new month begins.

- The Babylonians do not greet [rabbinic authorities], so Z'eira [respected their custom and] did not greet Rabbah when he visited.

- Rabbi Yohanan said to Rav Hiyya bar Bo: “The Babylonians have brought two [customs] up with them: full prostration on the fast days and the taking of the willow on the seventh day [of Sukkot]. The Rabbis of Caesarea added bloodletting [to the list] as well.

- In the Babylonian Talmud we find: “Yosef.” In the Jerusalem Talmud: “Yosi.”

- (7) “There, in Babylon, when there is no wine, the prayer leader descends to the bima and recites the one blessing in place of seven and concludes with meqadesh Israel v'et yom hashabbat.” However, in the Babylonian Talmud we do not find this.

- (8) In Babylon the custom followed Rabbi Ishmael in reciting “borkhu et hashem hamevorakh.” It appears that in the Land of Israel they followed Rabbi Akiva [instead].

- (9) Is seems that in the Land of Israel, when a Kohen was called to the Torah reading in the absence of a Levite, he would not recite a second blessing. In Babylon he recites the benediction.

- (10) In the Land of Israel they recite “Barukh shem kavod malkhuto l'olam va'ed” out loud because of the heretics. In Nehardea they whisper it since there are no heretics there.

As you can see, the numbering switches from Hebrew to Latin after tet. This is probably because the tet resembles a six, so he followed it up with seven. Remember, these were just personal notes, not intended for publication, obviously. Rabbi Singer's mind was on more important things, as the erudition of his notes speaks for itself. Anyway, who was Rabbi Singer? We'll return to that at the end of this post. Here in the middle of the work there is a citation apparently to a Yalkut in Parshat VaYeshev, but I can't make heads or tails of it.

Appendix to Lewin's edition. The articles originally appeared in Sinai 10 and 11.

Like Zinger, Lewin also noted the additional Hiluqim in Miller's volume and decided to add more. Instead of adding exclusively from Talmudic sources, Lewin leaned more on Geonic sources, of which he was the great master. Some of these additions are quotations, and some Lewin formulated himself.

1. After completion [of the section from the public reading], the reader blesses: “Blessed are you … ruler of the world, rock of ages, righteous of all generations, the steadfast deity ...” Then the congregation promptly rise and say: “Steadfast are you, he, the Lord, our G-d, and steadfast is your word. Steadfast, living, and lasting is your name and it's utterance. Always will you rule over us forever and ever.” This is one of the disputes between the sons of the East and the sons of the West, for the sons of the East respond while sitting whereas the sons of the West [respond] while standing.

2. In Zoan, Egypt, which is called Fustat [today part of old Cairo], there are two synagogues: one for the people of the Land of Israel, the al-Shamiyin congregation [=the "Yerushalmi", this name is still used today to refer to a Jewish Yemenite branch] (It is named after Elijah, of blessed memory [?, see below]). The other is the congregation of the people of Babylon, the al-Iraqiyn congregation. They do not observe the same customs. (Selections from Yosef Sambari, Seder HaHakhamim, Neubauer I, p. 118. On page 137 it states that the congregational synagogue then still in use was built before the destruction of the second temple in Jerusalem.) One, (the people of the Land of Israel) stands during kedusha, while the other, (that of the residents of Babylon) sit during kedusha. (Rabbi Avraham ben HaGra, Maspiq l'ovdei hashem.In the 1989 edition published by Nissim Dana, page 180, the opinions appear in reverse order)

3. It is written in the responsa of the Geonim that the residents of the Land of Israel recite kedusha only on the Sabbath, since it is written [in Isaiah 6:2] that the Hayot have six wings. Each wing sings praises corresponding to the days of the week. When the Sabbath arrives, the Hayot say to the holy one, blessed be he: “We do not have another wing!” He replies to them: “I have another wing which sings praises to me, as in (Isaiah 24:16): “From the end [literally: wing] of the world we have heard song.” (Tosafot Sanhedrin 37b, ad. loc. Mikanap, Miller 59)

4. We do not recite kadish or borkhu with any less than ten [men]. Our sages in the west recite it [in the presence] of [even] seven [men]. They explain themselves according to the verse: “bifroa p'raot ...” (Judges 5:2) according to the number of words [in the verse = seven. See also verse 5:9.] Some recite it with even six [men] since [the word] borkhu is the sixth [word in the verse]. (Some base this opinion on Psalms 68:27, which contains six words – Avudraham)

5. R. Joseph said: How fine was the statement which was brought by R. Samuel b. Judah when he reported that in the West [Israel] they say [in the evening], “Speak unto the children of Israel and thou shalt say unto them, I am the Lord your God, True.” (Berakhot 14b, Soncino translation). Still now, several cities [alternatively: regions] in the Land of Israel observe this custon in the evening. They reason that shema and v'haya im shamoa, [the first two paragraphs], are observed both day and night, whereas va'yomer is only observed during the day [as per Mishna Berakhot 2:2]. (Hilkhot Gedolot 1, Hilkhot Berakhot 2, p. 37, second Hildesheimer edition)

6. The sages of the Land of Israel behave as follows: they recite the evening prayers and later they read the Shema in its proper time. They are not concerned about connecting [the blessing ending with] geula to the evening prayers. (Sha'arei Teshuva 76, See Otzar HaGeonim for a list of numerous rishonim and collections who cite this responsum.)

7. Conserving a festival which begins after the Sabbath, it is still maintained in the Land of Israel that a fourth blessing is recited separately... but as for us, Rab and Samuel instituted for us a precious pearl in Babylon: “Just judgements and true Torah.” (attributed to Rav Hai Gaon, Otzar HaGeonim Berakhot, Perushim p. 46)

8. On the final day of the festival miṣwot u'ḥuqim and bekhor are read (Megilah 31a, acc. to mss. Munich and rishonim). Rav Hai Gaon explains this passage as a mnemonic sign: 1. There are those who read “for this miṣwa” (Deut. 30:11) and this is still read in the Land of Israel. 2. There are those who read from “im be'ḥuqotaiuntil “qomemiut.” (Lev. 26:3-13) 3. There are those who read: “kol ha'bekhor” (Deut 15:19). We read “kol ha'bekhor.” (various sources, Otzar HaGeonim Megillah, p. 62, no. 230)

9. Upon the conclusion of the Day of Atonement, residents of the Land of Israel blow qashraq [=tashrat, a serious of various tones]. Residents of Babylon only sound one plain blow in remembrance of the jubilee. [From here until the end, Lewin composed most of the statements himself based on the sources he provides.]

10. The three fast days – Ta'anit Esther – are not observed consecutively, but rather, separately: Monday, Thursday, and Monday. Our sages in the Land of Israel were accustomed to fast after the days of Purim, on account of Nicanor and his company. Also, we delay [unpleasant] payment and do not predicate it. (Masekhet Sofrim 17)

11. Residents of the Land of Israel would not actually fully prostrate themselves on fast days. Residents of Babylon would actually fully prostrate themselves.

12. Residents of the Land of Israel did not read Hallel at all on the day of the New Moon. Residents of Babylon read it while skipping sections [an abbreviated version].

13. Among residents of the Land of Israel, the first reader from the Torah recites the beginning blessing, and the last reader recites the final blessing. According to the residents of Babylonian, each and every reader blesses before and after the reading, since [members of the congregation may be] coming and going [during the readings and thus miss one or the other].

14. In the absence of a Levite, residents of the Land of Israel would call a second Kohen to read from the Torah in his place. Residents of Babylon would call up the very same Kohen again who just read the first portion.

15. Residents of the Land of Israel permitted writing [Torah] scrolls on the skins of pure animals even if they were not slaughtered according to specifications of dietary laws. Residents of Babylon forbade this since they were not slaughtered.

Translated summary of selected sections of Margaliot's introduction

Margulies' Table of Contents

[The entire Table of Contents of Margulies has been translated. However, only a summary of chapter 2 and the text of the original work itself have been translated here.]

Chapter 1

Relations between Babylon and the Land of Israel from the close of the Talmudic period until the close of the Geonic period

1. The end of the Talmudic Period

2. The Geonic period

3. Attitudes towards divergent customs until the Geonic period

4. Attitudes of Babylonian Geonim to the customs of the Land of Israel

Chapter 2

The Book of Disputes between East and West, the nature of the work and its use by Rabbinic and Karaite Jews.

1. The name of the work

2. The author, his period, and locale

3. Purpose of the work

4. Characteristics and scope of the book

5. Language and sources

6. Legal sources and historical development of the disputes

7. Use of the book by Geonim

8. Use of the book by Rabbinic legal authorities

9. Use of the book by Karaites

10. Scholars who have studied the work

Chapter 3

Textual sources of the Book of Disputes, Printed Editions and Manuscripts

1. Text versions, families and formation

2. The first group

3. The second group

4. The third group

5. This edition's presentation and stemmatic diagram of source relationships

6. The varying order of the disputes in all of the versions

7. The text

Presentation of the actual text with variant apparatus

Sources, History, and Development of the Disputes [Systematic Commentary]

Chapter 1 is a general introduction to the context of the work and is not translated at this time

Chapter 2 Summarized in translation

1. The name of the work

The work appears in numerous manuscript versions and cited by various Rishonim. Virtually every single one has a different title for the work – all variations on the same descriptive theme. [Both the variation in titles and the descriptive nature suggest that the work may have been not only anonymous, but also untitled. It was simply a list drawn up by a sage, copied and possibly added to.]

The majority of sources contain a variation of the root ḥlqin the title, including the first printed edition (1616, starts at middle of page) included at the end of Bava Kamma in Yam shel Shelomo, by the great Ashkenazi sage Rabbi Solomon Luria, better known as Maharshal (1510-1573).

![]()

I don't know who decided to include the work in Maharshal's edition, it led some to believe that the Maharshal himself collected it, a point justly disputed by Rav Avraham ben HaGra [see below].

Margulies is perplexed as to why Miller chose a title based on the root ḥlp, which only appears in a few secondary sources like Ravya, Rosh, and Tur.

[Lewin also followed Miller on this point. It seems that the selection of this root was designed to minimize the controversial nature of the work. As Lewin stresses in his introduction, this is a work of divergent customs, not disputes regarding actual Torah law. The reader can evaluate both titles, which have themselves both been translated here as “alternates”. In this writer's opinion, both of the roots may be “alternate” variations of one original word (probably from the root ḥlq)as the letters pehand qof are graphically similar. A supporting example of variation between these very same words is found in The Epistle of Rav Sherira Gaon in the “French” manuscript branch. See Lewin's edition, page 22, left column, note 19. There you will find a manuscript with precisely such an alternate reading.

Also of note is that certain Islamic literature which records divergent legal opinions is referred to as kḥilaf. See here, beginning of intro. On the other hand, an 11thcentury Karaite work is entitled Ḥilluq ha-qara'im we-ha-rabbanim]

2. The author, his period, and locale

The author is anonymous, and we have no clue as to his identity.

The first serious recorded attempt to date the work is by Rabbi Abraham ben Elijah of Vilna, the son of the famous GRA, in his work Rav P'alim, p. 126. He was uncertain as to whether the work was authored by amoraim or in a later period. [His chief concern here is disproving the erroneous theory that the Maharshal himself collected the work from various rabbinic sources.] Miller was able to hone in closer, from the savoraim at the close of the Talmudic period to the beginning of the Geonic period. Margulies provides considerable evidence that the work was composed around the year 700. That is, after the Arab conquest and before Rav Yehudai Gaon.

According to Miller, our author was a native of the Land of Israel and familiar with Babylonian customs through travel to Babylon. Western Aramaic and Western Hebrew forms abound. In fact, the very composition in Hebrew suggests composition in the land of Israel, the language of the “Minor” Talmudic tractates produced there during the Geonic period, as well as Hebrew translations of Eastern Aramaic Babylonian Geonic works themselves. Margulies points out that since Miller's publication, new evidence has emerged from the Cairo geniza which shows that after the Arab conquest, Babylonian Jews migrated to the Land of Israel and formed their own separate congregations in Tiberias, Ramla, and Mivtzar Dan (Panias-Banias), with the most likely speculative location for our author being Tiberias, which was a native Torah center that may have already boasted a Babylonian community during the Talmudic period.

3. Purpose of the work

According to Miller, the work was designed to oppose the Babylonian side in the dispute between the two great Torah centers. He points out that many more explanations are offered in support of the "Yerushalmi" side than the Babylonian. Later, Miller appears to backtrack and seems to conclude that the work is simply meant to impartially catalog the various discrepancies.

Margulies accepts the claims regarding the basic "Yerushalmi" orientation, but understands the purpose more subtly. Rather than taking a confrontational stance, the work merely seeks to explain and rationalize the local customs and decisions to the new Babylonian immigrants who were not aware or respectful of the locals. No attempt is made per se to reject the validity of the Babylonian customs themselves and at times the author troubles himself to explain them only.

4. Characteristics and scope of the book

The items in the work are haphazardly arranged with only occasional grouping according to topic. It is nowhere near complete in cataloging all of the items of dispute. According to Miller, the complete version of the work has not yet been transmitted to us. [This understanding may underly many efforts to expand on this list, discussed in the Appendix.] Margulies disagrees, on the basis of the numerous manuscript examples at his disposal. According to him, the author never meant to compile an exhaustive list.

5. Language and sources

It has already been pointed out that the work was composed in "Yerushalmi" Hebrew. A list of words and phrases is provided by Margulies along with parallel examples from Talmudic and Geonic "Yerushalmi" literature. He supposes that many more parallels would be found in halakhic works from the period and region which are no longer extant.

[This section is of considerable philological interest especially regarding Geonic material in Hebrew which may be of uncertain provenance.]

6. Legal sources and historical development of the disputes

Most of the items can be documented partially in other Talmudic and Geonic literature. As would be expected, there is a high level of correspondence between the "Yerushalmi" side and the Jerusalem Talmud; also, between the Babylonian side and the Babylonian Talmud.

Most of the items appear to predate the collection and stem from the Talmudic period, many probably earlier, from the Tannaitic period.

In some cases, a Tannaitic dispute may have been transmitted unresolved to both regions and eventually decided differently in each locale in a purely internal manner. Conversely, sometimes entirely external factors may drive the discrepancies in later periods as well.

Of special interest is following the disputes from the Geonic period until the end of the period of the Rishomin signified by the publication of the Shulhan Arukh. In general, the Babylonian side prevailed as their hegemony increased, but in a number of cases, the position native to the Land of Israel in fact dominated, especially when it did not contradict any explicit statements in the Babylonian Talmud. This tradition was especially strong in Tsarfat and Ashkenaz (France and Germany) as opposed to Sepharad (Spain), which historically remained tied to the Babylonian Geonim. The influence of the Land of Israel side is especially noticed in the house of study of the great Rashi and his students (items 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 13, 14, 18, 19, 25, and more).

The period following the publication of the Shulhan Arukh is not discussed systematically in Margulies' commentary since to a large extent geographic boundaries were erased by the free transfer of books from one region to another and a great amount of cross-fertilization occurred. Nevertheless, it is noted that a number of disputes remain with us to this very day between Ashkenazi and Sepharadi communities.

7. Use of the book by Geonim

In Babylonian Geonic responsa literature, a number of disputes are addressed, but apparently not through direct exposure to the work. It is more likely that the inquirers from the Land of Israel or North Africa might have been motivated in their queries by exposure to concepts from the work.

However, the later European collections of Geonic material did see fit to gather material from this work into their nets. The collection known as Sha'are Tsedeq includes no fewer than eleven items culled from the disputes.

In a few cases, items from the collection are attributed to Babylonain Geonim themselves, but it is difficult to rely on any of these attributions and most were clearly added by the later compiler.

8. Use of the book by Rabbinic legal authorities

Many of the great authorities were most probably unaware of the work as they never cite it or it's contents. Others who do cite it generally cite only sections known to them through second or third-hand rabbinic sources.

Geographic location was clearly a major factor. In France and Provence use was much more pronounced than in Spain. The work seems to have reached different locations at different times. By the 14th century the work seems to have been lost for the most part, as only citations from by previous authorities are ever quoted.

One reason for the neglect of this work may have been it's brevity. [For example, the usual explanation for the grouping of the twelve prophets in one scroll, and today in one volume, is so that the small books would not become lost.] However, a more compelling reason appears to be the negative impression that the work made on certain authorities, most notably, Nahmanides, Ramban (Avodah Zara 35b). It was (correctly) perceived that the work contains material which contradicts the Babylonian Talmud, already considered supremely authoritative. Methods of study which stressed a proper historical understanding of all legal points of view would become common in rabbinic circles well before the modern period, but at the time they were not yet developed. If an opinion could not be utilized for determining the halakha, it was not deemed worthy of further inquiry. Nahmanides is the only early Spanish sage who even mentions the work, so it is not at all surprising that he considers it outside the pale of legal precedent.

Possibly, the Spanish Sages resisted the work as a result of the utility that Karaites received from it and quoted from it. They may have suspected the work of being a Karaite forgery.

In contrast, early Provencal authorities made ample use of the work. They include: Rabbi Abraham ben Isaac of Narbonne (Eshkol), Rabbi Isaac ben Abba Mari of Marseilles (Ittur), and Rabbi Abraham ben Nathan of Lunel (Manhig). The textual versions cited by the Provencal sages are similar to those found in the Geonic Responsa collections which appear to be most original.

Ashkenazi sages also utilized the work widely, but the stylized textual citations indicate that they were generally quoting secondary and tertiary rabbinic sources rather than the work directly. The sages include: Rabbi Eliezer bar Nathan of Mainz (Ra'avan, Even Ha-Ezer), Ravya, Tosafot, Rabbi Eliezer of Metz (Yereim), Sha'arei Dura, Machzor Vitry.

From the fourteenth century on mention and discussion of the work seems to virtually disappear. A most notable exception is Rabbi Ashtori HaParḥi (Isaac HaKohen ben Moses, 1280-1366) in his Kaftor w-Ferah, who traveled from France to the Land of Israel, on which his work focuses. He cites the work according to versions not attested to otherwise among French sages. [Furthermore, he took an interest in expanding upon the principle of the work as seen in the additions which Miller culled from it. See below after the main body of the translation.]

Students of the Maharam of Rottenberg, such as Hagahot Maimoniot, Mordechai, and Rabbenu Asher ben Yehiel (Rosh) mention the work haphazardly. Other sages who cite the work include Rikanati, Tashbatz, Agur, Or Zarua, and Shiltei Giborim. None of the early or later sages undertook an elucidation of the entire work – they left this important work for us to do!

9. Use of the book by Karaites

Karaites took a much keener interest in the disputes than Rabbanites. This is not at all surprising. The Rabbanites claimed to possess an authoritative Talmudic tradition handed down from the earlier sages. Every known dispute amongst the Talmudic sages themselves was utilized in order to argue against these claims. From Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai to disputes amongst the Babylonian Geonim themselves, the Karaites seized upon the disputes between East and West eagerly.

The first Karaite sage to quote the work is Jacob Qirqisani (10th century). Since he cites the work in an overtly apologetic manner (read: missionary), he was wont to exaggerate and even forge sections of the work. Thus, it goes without saying that his work cannot be utilized uncritically. Nevertheless, despite this cautionary note, his early explanations can at times be very useful in understanding the nature of the disputes themselves.

He explains his interest in the disputes very clearly. According to him, the disputes between East and West were more extensive than the disputes between the Rabbanites and the Karaites, but nevertheless, claims of heresy were never leveled and a spirit of tolerance reigned between the communities. So too, the Karaites should be accepted by the Rabbanites . This stance led him to exaggerate at times the extent of the disputes which were considered normative. Thus, even though the majority of the disputes concern extra-legal customs, he would attempt to thrust them into the body of the legal arena as exemplars of radical opinions. If at times he may have honestly misunderstood the disputes, in some of them it appears that he was making a cynical attempt misrepresent them and create confusion to advance his rhetorical purposes.

One example which stands out is a dispute which Qirqisani appears to have invented out of whole cloth, an out and our forgery not attested to in any other versions of the work:

“People of Babylon do not permit one to betrothe a woman with [the fruit of] the seventh year. People of the Land of Israel permit this. Therefore, the betrothals of that year in the Land of Israel are not considered by the Babylonians to effect marriage, and their children are not valid.”

[According to Mordekhai Akiva Friedman (Madaei HaYahadut 31), a maculation of taba'atto shevi'it resulting from graphic similarity between the letters tetand shin led item 25 to be misconstrued by Qirqisani in this manner. If Lewin did not mention this possibility, at the very least, he noticed the similarities and listed them together in his collection.]

From Qiqisani's time on, Karaites have continued to utilize the work in their own disputations with Rabbanites. As we saw earlier, this may have led to the work's falling out of favor among Rabbanites in regions where Karaites were active.

10. Scholars who have studied the work

2. Dr. P. P. Frankl in Monatscrifft,1871 (Heft 8), p. 352-363 (available through compactmemory)

5. Rabbi Gershon Hanoch Leiner, the Admor of Radzin, in his commentary to Orchot Hayyim, mentions that he has composed commentaries on 50 disputes from the work. This has not been published and according to Margulies may no longer be extant.

7. R. Ezra Altshuler, Tosefta, 1899. According to Lewin and Margulies, he plagiarized Miller (3 above) without mentioning him at all, even copying his printing errors. Someone should do a study on this work and figure out if the accusations are justified. Both Eliezer Brodt and I suspect that R. Ezra did, in fact, add plenty of his own material and didn't see anything wrong with copying transcriptions from a previous edition. This version of the Hiluqimhas been republishedwith additional notes from the Aderes.

9. R. Ya'akov Shor, Ner Ma'aravi in HaMe'asef, 1910 [for a complete listing of all issues containing this serial column, see Simha Emanuel's index, entry 98]. These were reprinted in כתבי וחדושי הגאון רבי יעקב שור זצ"ל.

10. R. Dr. Benjamin Menashe Lewin, Otzar HaGeonim, [Otzar Hiluf Minhagim, 1942. Lewin's edition was prepared more or less simultaneously as Margulies' edition. Forthcoming from R. Yosaif Mordechai Dubovickis a study on the various versions of Lewin's publication.]

12. [After over a Jubilee of reliance on the two critical editions of Marulies and Lewin, without further critical study, Ze'ev Elkin re-opened the field with his 1997 Tarbiz article focusing on the earliest manuscripts of the work, which are all of Karaite origin. He questioned several of Margulies conjectures. Elkin later became a member of the Knesset.

13. R. Dr. Uzi Fuchs, Netuim 2003. An examination of the Rothschild manuscript and its role in the development of the various textual variants.]

Hillel Neuman in Ha-Ma'asim 2011 discusses several items from this related work in passing. This is a new revised version of his 1987 master's thesis(Hebrew University).

Chapter 3 Textual sources of the Book of Disputes, Printed Editions and Manuscripts

[This technical section has not been translated, except for the last section, the text itself, found at the beginning of this article. According to Elkin's 1997 article the textual analysis may be in need of an update and revision.]

Now that we are finished duscussing the Hiluqim, we can return to the question about who Rabbi Benjamin Zev Singer was. Rabbi Singer published Hamadrich, a Talmudic anthology, in collaboration with his brother, Rabbi Abraham Singer of Varpalota in 1882 and Das Buch der Jubiläen (Die Leptogenesis) in 1898 as “Wilhelm Singer.” Also, Neue Lehrmethode für den hebräischen Lese- und Sprachunerricht in der ersten Klas in 1867, with an additional Hebrew subtitle, אור חדש. This is a slim German Sefer Mesores for learning the Hebrew alphabet, davvening, handwriting, and selected phrases in Judeo-German.Singer is identified as a hauptschullehrer, a schoolteacher.

R. Daniel Sperber published a volume of Rabbi Singer's novella/hiddushim on Tractate Shabbat in 1986 and included a biography of him:

That biography is incorporated in a list of his many unpublished Hebrew works still in manuscript which are housed in boxes at Bar Ilan. Apparently University of Toronto houses manuscripts of his writing in German (maybe Hungarian, too, but he wrote both of his books in German. I noticed that at least one of the items Singer listed above (four mil) is apparently given fuller treatment in these manuscripts. Given the sheer quantity of his output, I suspect that many more items in the list are as well.

On the title page of the book, Singer lists a couple of learned review articles in German of the Miller volume. See it here:

One review appears in Graetz's Monatsschrift, 1879, pp. 87-91 (Heinrich Graetz took over as editor after Zecharias Frankel); the other is in Brüll's Jahrbuecher, vol. 4, pp. 169-173. (Both are available at www.compactmemory.de.) A couple of other articles are listed here as well, after the fact. At the top, the aforementioned 1871 Monatsschrift article of Dr. P. P. Frankl (listed by Marguleis), p. 357. At the bottom, an additional Brüll Jahrbuecher article from the first volume of the series, p. 44, where Talmudic customs of the Galil and Judah are discussed.

It is quite interesting to see that the Rabbi Singer brothers, the authors of HaMadrich, featuring haskamot of R. Yitzchak Elchanan Spector, the Netziv, and (over a hundred!) gedolim, had an openness to modern scholarship which accommodated Graetz and even Brüll, a reform rabbi who for a time headed the congregation in Frankfurt opposite R. Shimshon Raphael Hirsch. This openness is also manifest in the very existence of R. Singer's volume on the book of Jubilees, Seforim Hitzoni'im.

Another point worth mentioning is that HaMadrich is essentially a collection of chapters to be learned by beginning and intermediate students all in one volume with an eclectic running commentary. That work was briefly touched on in this forum previously, but it would be more interesting to explore in greater detail exactly how eclectic it was once we have a clearer picture of the depth of lomdus and of academic scholarship displayed by the authors of this first “Artscroll.”

This “openness” of the Singer brothers did not appeal to everyone. R. Yehoshua Monsdhein's article on HaMadrichdetails the controversy surrounding the work. It is difficult to piece together exactly to what extent the opposition was to any change whatsoever in the education process, and to what extent it was towards entrusting the enlightened Singer brothers to this task.

If it can be compared were these haskamot procured (many of them probably after the controversy already developed!) any more successful than the ones in Rabinowitz's Dikdukei Sofrim? How many lomdim actually learned with HaMadrich? It was only reprinted once and then again twenty years ago.

Back to the Hiluqim notes, It seems to me that except for the first Monatsschrift review, the additional three references were added in pencil by another hand, perhaps R. Singer's brother R. Abraham, who worked closely with him on HaMadrich. But probably not the other way around. I consulted with R. Yechiel Goldhaber– he thinks that these notes are in the same style as the published hiddushim on Shabbat, and that seems quite reasonable.

Thanks to Lucia Raspe for deciphering these journal references, and to Sara Zfatman for the assist.

---

Translator's note: Thanks to Avi Kessner for suggesting and sponsoring this project, also for proofreading and valuable comments. I am indebted to Sander Kolatch and the Kolatch Foundation for general assistance during the year. Eliezer Brodt provided several useful references, without which this post would have been much poorer. The Guetta, Jacobi, and Peled families who continue with their unfailing support, especially my wife Dana, who makes it all possible. This translation is dedicated to my father, Nathan ben Tzipporah, in the hope that he should enjoy a complete and speedy recovery.